Abstract

This paper examines South Africa’s economic and political status within Southern Africa against the backdrop of domestic coalition governance, global geopolitical pressures, and regional transformation imperatives through February 2026. Drawing on recent economic data, policy developments, diplomatic initiatives, and regional security analyses, the analysis demonstrates how South Africa navigates the paradox of continued regional dominance alongside mounting structural constraints. The paper argues that South Africa’s status in Southern Africa is best understood through three interconnected dimensions: as an indispensable economic anchor whose trade integration, industrial capacity, and infrastructure networks shape regional development patterns; as a contested political leader whose constitutional foreign policy orientation creates both diplomatic credibility and geopolitical friction; and as a security partner whose peacekeeping commitments and border management strategies affect regional stability. The convergence of domestic reform pressures, global power realignment, and regional integration imperatives creates both challenges and opportunities for South Africa’s regional leadership in an increasingly multipolar environment.

Keywords: South Africa-Southern Africa relations, regional hegemony, constitutional foreign policy, SACU integration, SADC security architecture, African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

Introduction

The Republic of South Africa occupies an unparalleled position in Southern African international relations. As the continent’s most industrialized economy, the region’s logistical gateway, and a constitutional democracy with significant soft power assets, South Africa fundamentally shapes the economic and political environment within which its neighbors operate. Yet this dominance coexists with persistent domestic challenges—subdued growth, unemployment exceeding 30 percent, infrastructure constraints, and coalition governance following the African National Congress’s loss of parliamentary majority—that constrain regional leadership capacity and generate contested perceptions of South Africa’s role .

This paper investigates a central research question: What is South Africa’s current economic and political status within Southern Africa, and how is this status being reshaped by domestic political transitions, global geopolitical pressures, and regional integration dynamics? The significance of this inquiry extends beyond South Africa’s bilateral relationships. As the anchor of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), the largest economy in the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and a key player in continental institutions, South Africa’s trajectory substantially influences regional development prospects, governance norms, and security outcomes.

This paper proceeds in five sections. Following this introduction, Section Two examines South Africa’s domestic political economy, establishing the foundational context for its regional engagement. Section Three analyzes the country’s economic status in Southern Africa, focusing on trade integration, infrastructure networks, and industrial policy. Section Four investigates political and diplomatic leadership, including constitutional foreign policy orientation and multilateral engagement. Section Five addresses security cooperation and regional stability architecture. The conclusion synthesizes these findings and offers prospective analysis.

1. South Africa’s Domestic Political Economy: Reform Pressures and Coalition Governance

South Africa’s external status in Southern Africa cannot be understood without first examining its domestic political and economic trajectory. The Government of National Unity (GNU), formed after the ANC lost its parliamentary majority in the 2024 elections, represents a fundamental shift in governance dynamics with implications for regional engagement.

1.1 Macroeconomic Context and Reform Imperatives

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s February 2026 State of the Nation Address (SONA) revealed an economy showing signs of recovery while confronting deep structural challenges. The country has experienced four consecutive quarters of GDP growth, and the Johannesburg Stock Exchange “has performed exceptionally well over the past year” . The Rand has strengthened against the Dollar, and government is “on a clear path of stabilising our national debt” .

However, these positive indicators coexist with recognition that growth remains insufficient to address South Africa’s social and economic challenges. Ramaphosa acknowledged that “while we have experienced four consecutive quarters of GDP growth, we know that it has to grow much higher and much faster to meet our social and economic challenges” . This tension between recovery and transformation defines the domestic context for foreign policy.

The 2026 SONA was delivered against a complex domestic and global backdrop, “marked by subdued economic growth, infrastructure constraints, geopolitical tensions and rising pressure on the government to demonstrate tangible progress under the Government of National Unity” . Notably, Ramaphosa placed “short term and immediate deadlines for his policy implementations” regarding organized crime, the growing water crisis, and the ongoing Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Criminality, Political Interference, and Corruption . This emphasis on delivery reflects awareness that the 2026 local government elections “might well add to the ANC’s declining support if the political pundits’ predictions are to be believed” .

1.2 Coalition Governance and Policy Continuity

The Government of National Unity has placed economic growth and job creation at the centre of its strategy, with the 2025 SONA centered on three pillars: economic growth, job creation, and creating a capable state . This represents significant policy continuity despite the changed political configuration, suggesting that core economic priorities enjoy cross-party support.

The GNU’s composition—with the ANC governing alongside opposition parties including the Democratic Alliance—creates both opportunities and constraints for foreign policy. On one hand, coalition governance may enhance policy predictability by constraining radical shifts; on the other, it requires continuous negotiation that can slow decision-making and complicate responses to external crises.

1.3 Domestic Challenges with Regional Implications

Several domestic challenges carry direct implications for South Africa’s regional status. Infrastructure constraints, particularly in electricity supply and logistics, have historically limited growth and affected regional trade flows. While Ramaphosa declared that “the era of load-shedding is now a thing of the past” in February 2026 , sustained improvement will require continued investment and operational discipline.

The water crisis represents an emerging challenge with potential regional dimensions. Ramaphosa announced plans to address the “country’s growing water crisis” , which affects not only domestic users but also downstream neighbors and agricultural exports. Given South Africa’s role as a regional food supplier, water security has cross-border implications.

Crime and illegal mining have prompted deployment of the South African National Defence Force to provinces including Gauteng and the Western Cape . These deployments affect regional perceptions of South Africa’s internal stability and its capacity to manage cross-border criminal networks.

2. Economic Status: Trade Anchor, Infrastructure Hub, and Regional Value Chains

South Africa’s economic status in Southern Africa is defined by its role as the region’s dominant trade partner, investment source, and infrastructure hub. Understanding this position requires examining trade patterns, regional integration frameworks, and industrial policy.

2.1 Agricultural Trade Dominance

South Africa’s agricultural exports illustrate the depth of regional economic integration. The African continent accounts for roughly half of the country’s annual agricultural exports, valued at approximately $13.7 billion (R237 billion) in 2024, with expectations of exceeding $14 billion in 2026 . This export performance positions South Africa as the region’s primary food supplier.

Critically, roughly 90 cents in every dollar of South Africa’s agricultural exports to the African continent go to Southern African countries, primarily within SACU and the SADC Free Trade Area . This concentration reflects both geographic proximity and deep integration through regional trade agreements. The grain industry is a major exporter to the region, with “roughly half of exports typically to the region each year” .

The product scope of agricultural exports into SACU and SADC is diverse, including “maize, processed food products, apples and pears, sugar, animal feed, prepared or bottled water, fruit juices, and wine” . This range demonstrates South Africa’s capacity to supply both basic food security commodities and higher-value processed products.

2.2 Regional Integration Frameworks: SACU, SADC, and AfCFTA

South Africa participates in multiple regional integration frameworks that structure its economic relationships with neighbors. As the largest economy in SACU, South Africa’s trade patterns and tariff policies significantly affect customs revenue flows that constitute substantial portions of neighboring states’ budgets.

President Ramaphosa emphasized South Africa’s commitment to implementing the African Continental Free Trade Area, stating that “South African firms—our banks, farmers and manufacturers—will be leading suppliers to an African market of 1.4 billion people” . This vision positions South Africa as a primary beneficiary of continental integration while acknowledging that “for Africa to thrive, we must silence the guns on the continent” .

The AfCFTA’s potential to expand South African exports beyond Southern Africa confronts significant barriers. While South Africa’s “realistic opportunity” lies in East and West Africa, “at least in the near term, trade with these regions may not yield many benefits” . Three factors constrain expansion: “a range of non-tariff barriers, which could hinder boosting trade regardless of lower tariffs through AfCFTA”; “high levels of corruption, which increase the costs of doing business”; and “fragmented value chains owing to poor connectivity and infrastructure” .

This “narrow scope of expanding agricultural exports in the African continent typically leads to frustration among business leaders, who continue to see improvement in domestic production but are limited in avenues for sales” . Major economies like Nigeria and Kenya remain small markets for South African agricultural exports, “each accounting for a mere 2% per year” .

2.3 Export Diversification: Asia and the Middle East

Given constraints on African market expansion, South Africa’s export diversification agenda “increasingly points towards Asia and the Middle East as priority regions, including for grain and oilseed markets” . The “growing population and better income levels in these regions” provide attractive opportunities.

South Africa has resumed maize exports to Far Eastern destinations. Nearly 23 percent of the 897,891 tons exported between May and October 2025 was destined for markets including Vietnam, Taiwan, and South Korea . Agbiz has identified “China’s willingness to increase imports of South African agricultural products, including maize and soybeans, as a signal of opportunity for the grain and oilseed value chain” .

Tapping into these markets “will require more than just shipments – it will demand technical engagement, tariff barrier negotiations, and strong logistic systems to ensure grains and oilseeds can reach these regions competitively” . This diversification strategy does not diminish South Africa’s regional economic role but rather complements it, generating foreign exchange that supports overall economic capacity.

2.4 Industrial Policy and Special Economic Zones

South Africa’s industrial strategy increasingly emphasizes spatial development and regional value chains. The government has developed a Spatial Industrial Development Strategy to “accelerate the rollout of major catalytic industrial projects, which will benefit small businesses and communities across the country’s Special Economic Zones” .

The strategy aims to “strengthen the effectiveness of spatial initiatives, unlock private sector–led investment, and increase overall socio-economic impact” . Notably, it seeks to achieve “the greatest possible socio-economic impact” through “Afrocentric and transformative industrial enterprises with value-chain connections across several African nations” . This explicit regional orientation distinguishes the strategy from previous industrial policies focused primarily on domestic objectives.

Key components incorporate “green energy-related projects,” including an R18 billion investment project in Richards Bay led by the Nyaza project company. This project, “expected to transform the geography of Richards Bay, would be the largest since Sasol, focusing on beneficiation, value addition, and exports” .

The strategy’s success depends on leveraging the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement to “eliminate trade barriers and boost intra-African trade” . This linkage between domestic industrial policy and regional integration frameworks represents an important evolution in South Africa’s economic strategy.

2.5 Regional Infrastructure and Trade Corridors

South Africa’s infrastructure investments shape regional trade patterns and connectivity. Ramaphosa outlined plans to “improve infrastructure, grow industries, and attract investment,” including “roads, dams, ports and energy systems that boost economic activity” . These improvements, he argued, “will make trade easier not just within South Africa, but across Southern Africa” .

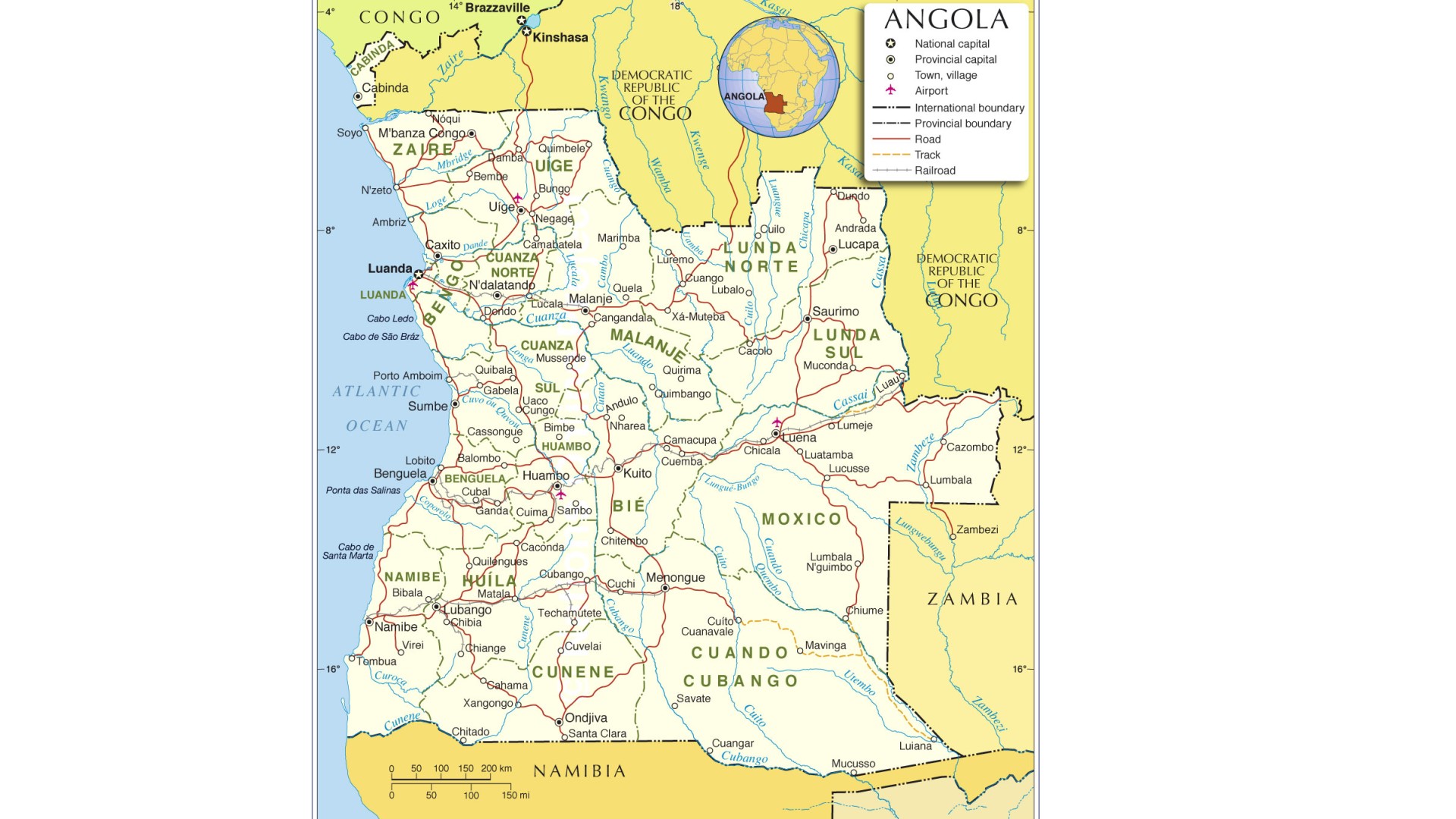

The 2026 Southern Africa Outlook identifies “regional integration and trade corridors” as central to unlocking growth, emphasizing “better transport, port and logistics infrastructure, linking landlocked countries to trade gateways, and leveraging regional value-chains” . South Africa’s ports—particularly Durban and Richards Bay—serve as critical gateways for landlocked neighbors including Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

However, port efficiency challenges have historically constrained regional trade competitiveness. Addressing these bottlenecks is essential if South Africa is to fulfill its role as regional logistics hub.

3. Political and Diplomatic Status: Constitutional Foreign Policy and Geopolitical Navigation

South Africa’s political status in Southern Africa is defined by its constitutional foreign policy orientation, multilateral leadership, and navigation of global geopolitical pressures. Recent developments reveal both continuity in principle and adaptation to a more contested international environment.

3.1 Constitutional Foreign Policy Doctrine

South Africa’s foreign policy is rooted in constitutional principles that shape its approach to regional and global affairs. A recent analysis argues that South Africa’s “diplomatic moment is no longer approaching… It has arrived” . In a world where “military power, economic coercion, and strategic intimidation increasingly replace law and institutions,” constitutional states must be “strategically persuasive” as well as “constitutionally correct” .

This orientation reflects South Africa’s historical experience, “where international legal pressure, multilateral mobilisation and normative isolation played a decisive role in dismantling apartheid” . Consequently, Pretoria has “consistently positioned international law, multilateral institutions and negotiated processes as essential correctives to power asymmetry in the global system” .

However, this approach confronts new challenges. As one analyst notes, “constitutional restraint is increasingly mistaken for unreliability” in a world where “diplomacy increasingly communicates through force” . This misreading “has material consequences, most importantly the economic cost of misinterpretation,” as “markets respond to signals, made by states, not footnotes” .

3.2 Multilateral Leadership: G20 Presidency and AU Engagement

South Africa’s G20 presidency represents a significant platform for advancing regional and continental priorities. Ramaphosa emphasized that the country will “use its leadership roles — including its historic presidency of the G20 — to advance these values globally and regionally, pushing for economic cooperation that benefits all” .

This presidency coincides with South Africa’s broader multilateral engagement, including its role in African Union governance and SADC structures. The country consistently advocates for “reform of the international financial architecture, restructuring of the UN Security Council, and enhanced African representation in global governance” .

3.3 Geopolitical Tensions: US Relations and Strategic Autonomy

South Africa’s foreign policy orientation has generated significant friction with the United States, reflecting broader divergence in approaches to global governance. Relations between Pretoria and Washington were “frosty by the end of 2025, following a year marked by escalating diplomatic and economic friction” .

Tension deepened following “higher tariffs on South African exports, uneven engagement around its G20 presidency and sharp disagreements over foreign policy positions taken by Pretoria in multilateral forums” . The US House of Representatives passed legislation requiring “a full review of America’s relationship with SA,” triggered by “opposition to Pretoria’s relations with Russia, China and Iran” .

The legislation’s sponsor, Republican representative John James, argued that “the ANC of today is no longer the party of Mandela” and that it “continuously moves away from its traditional stance of non-alignment in international affairs” . This critique reflects US concerns about South Africa’s engagement with strategic competitors.

South Africa’s response to events in Venezuela illustrated this divergence. After the US confirmed “a large-scale unilateral military operation in Venezuela that resulted in the capture of President Nicolás Maduro,” South Africa responded “in legal rather than diplomatic terms,” describing the strikes as “a manifest violation of the United Nations Charter” . The Department of International Relations and Cooperation confirmed that Pretoria would “formally approach the UN Security Council to request an urgent session” .

International Relations Minister Ronald Lamola articulated the principled position: “If we abandon international law, then might will always be right, and smaller countries will have no place” . President Ramaphosa reinforced this stance, “calling for the immediate release of Maduro and his wife” and framing the response as “consistent with its constitutional values, its liberation-era internationalism and its historic support for sovereignty, self-determination and the primacy of the UN Charter” .

3.4 Regional Diplomatic Coordination

Within Southern Africa, South Africa maintains active diplomatic engagement through multiple channels. Ramaphosa emphasized that “partnerships through the Southern African Development Community and African Union are central to building peace and shared prosperity across the continent” .

South Africa’s role in mediating regional disputes—including tensions between Botswana and Eswatini and engagement in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado crisis—demonstrates continuing diplomatic leadership. However, the emergence of other regional actors (notably Angola’s mediation in Eastern Congo) suggests a more distributed diplomatic landscape than in previous decades.

The Government of National Unity’s foreign policy orientation maintains continuity with established principles while adapting to coalition dynamics. Ramaphosa’s articulation of support for “self-determination, alongside solidarity with the people of Palestine, Western Sahara and Cuba” reflects positions with deep roots in ANC tradition that enjoy cross-party support.

4. Security Status: Peacekeeping, Border Management, and Regional Stability

South Africa’s security status in Southern Africa is defined by its peacekeeping commitments, border management strategies, and role in regional security architecture.

4.1 Peacekeeping and Regional Security Commitments

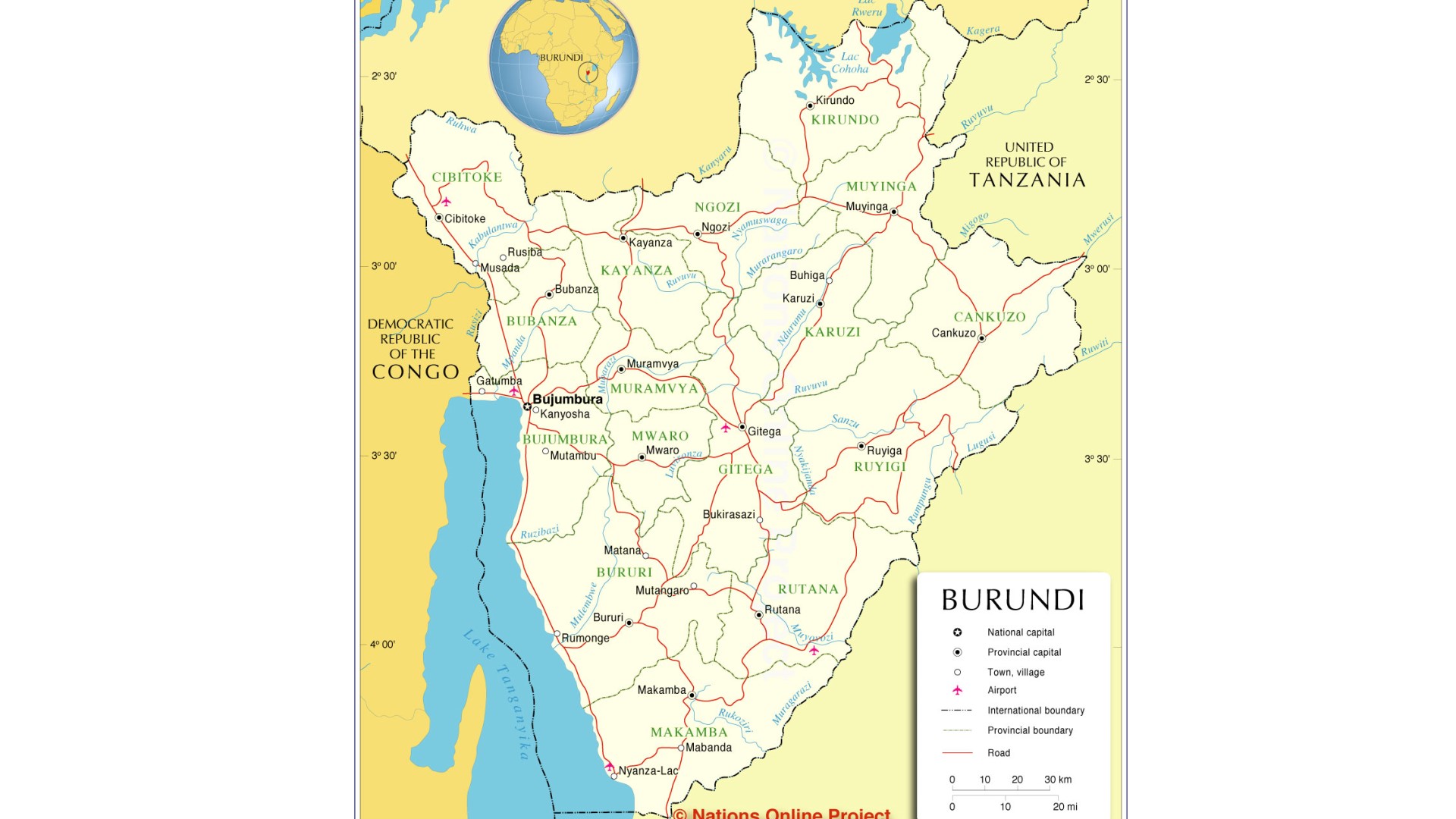

South Africa maintains significant peacekeeping commitments in the region, particularly in Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ramaphosa reminded Parliament that “South African peacekeepers were part of efforts in eastern DRC, where 14 soldiers recently lost their lives, saying this sacrifice shows Cape Town’s commitment to regional security and stability” .

The President emphasized that “for Africa to thrive, we must silence the guns on the continent,” highlighting South Africa’s “long-standing role in peace missions in places like Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo” . These commitments entail both human costs and financial burdens that test domestic political support for regional engagement.

The Cabo Delgado insurgency in Mozambique has required sustained regional attention. While South Africa has not taken the lead role in intervention, its military capacity and logistical support remain important for SADC collective responses. The evolving security situation continues to demand regional coordination.

4.2 Border Management and Cross-Border Crime

Border security has emerged as a prominent theme in South Africa’s regional engagement. Ramaphosa acknowledged “rising threats from organised crime, illegal mining and cross-border violence — which affect both domestic safety and regional economies” .

The President promised to “step up law enforcement and border security by investing in modern infrastructure, technology and cooperation between police and border agencies” . He explicitly stated that “illegal immigration poses a risk to our security, stability and economic progress,” while emphasizing that these concerns will be addressed “while still upholding human rights for everyone in the region” .

This approach “will directly impact countries like Malawi, where many South Africans and Malawians travel back and forth for work, study and trade” . The emphasis on “lawful movement and stronger border checks — including better entry systems and enforcement — signals that Pretoria wants orderly cross-border movement while discouraging illegal stays and dangerous smuggling networks” .

The deployment of the South African National Defence Force to assist in fighting crime and illegal mining in Gauteng and the Western Cape reflects the seriousness with which government views these threats. These internal security measures have regional implications, as cross-border criminal networks adapt to enforcement changes.

4.3 Regional Stability Architecture

South Africa participates actively in SADC security structures, contributing to collective responses to regional crises. The Southern Africa region entered 2026 in “complex terrain,” with growth “modest” and structural constraints limiting development . Security challenges compound economic vulnerabilities, creating need for coordinated regional responses.

The SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation provides framework for addressing shared challenges. South Africa’s diplomatic weight within this structure shapes collective decision-making, though the organization’s consensus-based approach requires building agreement among member states with diverse interests and capacities.

5. Comparative Positioning: South Africa in Regional Context

Understanding South Africa’s status in Southern Africa requires comparative perspective on its position relative to regional neighbors and evolving patterns of regional governance.

5.1 Economic Asymmetries and Interdependencies

South Africa’s economic dominance creates profound asymmetries in regional relationships. The country’s GDP exceeds that of all other SADC members combined, and its industrial base is uniquely diversified. This asymmetry generates dependencies that condition neighboring states’ policy autonomy while creating expectations of South African support.

However, interdependence also exists. South Africa depends on neighboring states for migrant labor, water resources (notably from Lesotho), and transit routes to landlocked countries. These dependencies create mutual stakes in functional regional relationships.

5.2 Comparative Governance and Democratic Credentials

South Africa’s constitutional democracy provides soft power assets in regional engagement, though governance challenges—including corruption concerns and service delivery failures—have eroded domestic and international confidence. The Government of National Unity represents an experiment in coalition governance that, if successful, could demonstrate democratic resilience.

Comparative governance indicators show mixed performance. While South Africa maintains independent courts, active civil society, and free media, perceptions of declining institutional quality affect its standing. The Zondo Commission’s findings on state capture continue to shape both domestic politics and international perceptions.

5.3 Demographic and Geographic Factors

South Africa’s population of approximately 62 million—by far the largest in Southern Africa—provides substantial domestic market scale that supports industrial development. Geographic position, with coastline on two oceans and borders with several neighbors, creates both opportunities and responsibilities.

The country’s nine provinces include regions with deep cross-border connections: Limpopo bordering Botswana and Zimbabwe, Mpumalanga bordering Mozambique and Eswatini, and Northern Cape bordering Namibia and Botswana. These subnational linkages complement national-level relationships.

Conclusion: South Africa’s Evolving Status and Future Trajectories

This paper has examined South Africa’s economic and political status within Southern Africa across multiple dimensions: domestic political economy foundations, trade and investment integration, constitutional foreign policy orientation, and security cooperation. The analysis reveals a country navigating fundamental tensions—between regional dominance and domestic constraints, between principled multilateralism and geopolitical pressures, between integration imperatives and national sovereignty concerns.

South Africa’s status in Southern Africa is best understood through three interconnected dimensions: as an indispensable economic anchor whose trade integration, industrial capacity, and infrastructure networks shape regional development patterns; as a contested political leader whose constitutional foreign policy orientation creates both diplomatic credibility and geopolitical friction; and as a security partner whose peacekeeping commitments and border management strategies affect regional stability.

Several factors will shape the future trajectory of South Africa’s regional position.

First, domestic reform outcomes will determine South Africa’s capacity for regional leadership. Successful implementation of structural reforms, infrastructure investment, and governance improvements would enhance credibility and capacity. Continued delivery failures would constrain regional engagement and erode soft power.

Second, coalition governance stability will affect foreign policy predictability and continuity. The Government of National Unity’s ability to maintain coherent external engagement while managing internal differences will shape regional perceptions of South African reliability.

Third, geopolitical navigation will test South Africa’s constitutional foreign policy doctrine. Balancing relations with major powers while maintaining strategic autonomy and regional credibility requires sophisticated diplomacy and clear communication of principled positions.

Fourth, regional integration implementation, particularly AfCFTA rollout and SACU modernization, will affect South Africa’s economic relationships with neighbors. Success in removing barriers and expanding trade would deepen integration and mutual benefit; failure would perpetuate fragmentation and underperformance.

The most significant finding of this analysis is the coherence of South Africa’s constitutional foreign policy orientation despite domestic political change and global pressures. Rooted in the country’s liberation history and constitutional framework, this approach privileges international law, multilateral institutions, and negotiated processes as essential correctives to power asymmetry. While this orientation creates friction with powers preferring unilateral action, it enjoys deep domestic legitimacy and aligns with the preferences of many regional partners.

For Southern African neighbors, South Africa’s status represents both opportunity and challenge: opportunity to access the region’s largest market, benefit from infrastructure investment, and coordinate on shared challenges; challenge to manage asymmetric relationships, navigate South Africa’s domestic politics, and maintain policy autonomy. Successful regional cooperation requires mutual understanding of these dynamics and sustained investment in institutional frameworks.

For South Africa itself, the region remains the primary arena for projecting influence, advancing development, and building coalitions for global governance reform. As President Ramaphosa articulated, the country’s success is “linked to the success of its neighbours,” requiring that “trade, security, immigration and economic cooperation must all work together if the region is to prosper in a competitive and changing world” .

The relationship between South Africa and its neighbors, in sum, reflects the complex interdependence of contemporary Southern Africa. As the region’s dominant economy and most established constitutional democracy, South Africa bears particular responsibilities for regional stability and development. Meeting these responsibilities while managing domestic transitions and global pressures will determine not only South Africa’s future status but the region’s collective capacity to navigate an increasingly uncertain global environment.

References

-

Ndenze, B. (2026, February 12). Jobs and debt reduction top agenda in President’s State of the Nation Address. EWN.

-

South African Institute of International Affairs. (2026, February 13). Global Turbulence and Regional Leadership: Post-SONA Dialogue on South Africa’s Foreign Policy in 2026. SAIIA.

-

Sihlobo, W. (2026, February 5). Why Asia beats Africa for new SA agricultural exports. SA Grain.

-

Invest Africa. (2026, January). 2026 Southern Africa Outlook Webinar. Invest Africa.

-

Legalbrief. (2026, February 10). Concerns over SA’s foreign policy reflected in key Bill. Legalbrief Africa.

-

Abedian, I. (2026, February 17). President Ramaphosa delivers SONA 2026 amid economic strain and reform pressures in an election year. GlobalSource Partners.

-

Cupido-Weaich, S.S. (2026, January 21). Constitutional States, Strategic Diplomacy, and the Fight for a Rules-Based World. African News Agency.

-

Nyasa Times. (2026, February 12). South Africa Shares New Plan to Work Better with Neighbouring Countries on Trade, Security, Immigration and Growing the Economy. Nyasa Times.

-

SAnews. (2026, February 19). Government develops strategy to accelerate industrial projects. SAnews.gov.za.

-

Mail & Guardian. (2026, January 9). Venezuela widens US-SA rift. Mail & Guardian.