Abstract

This paper examines the contemporary economic and political status of Western Sahara within the North African regional context as of early 2026, drawing upon United Nations Security Council resolutions, diplomatic reporting, economic data, and analysis from regional policy institutes. The research confronts a territory whose status remains fundamentally unresolved after five decades of conflict, yet whose geopolitical significance has never been greater. Western Sahara presents a paradoxical profile: a vast, resource-rich territory with significant phosphate deposits and Atlantic fisheries, yet one whose economic potential remains unrealized due to its disputed political status. Politically, the territory has witnessed a decisive diplomatic shift in 2025-2026, with the UN Security Council formally endorsing Morocco’s autonomy plan as the “most feasible solution,” marking the effective abandonment of the long-promised referendum on self-determination. This paper argues that Western Sahara’s regional position has been fundamentally transformed by this diplomatic realignment, which has isolated Algeria and the Polisario Front while consolidating Morocco’s claim to sovereignty. Yet the territory remains a zone of tension, with unresolved questions of resource exploitation, human rights, and the fate of Sahrawi refugees continuing to shape its contested present and uncertain future.

Keywords: Western Sahara, North Africa, self-determination, autonomy plan, Polisario Front, MINURSO, phosphate resources

1. Introduction

Western Sahara occupies a unique and deeply contested position in the North African geopolitical landscape. As Africa’s last remaining colony—a status recognized by the United Nations since 1963—the territory embodies the unfinished business of decolonization on a continent where colonial boundaries were largely transformed into sovereign states in the mid-twentieth century. Yet Western Sahara’s trajectory has diverged sharply from that of its neighbours: instead of independence or integration, the territory has experienced five decades of conflict, diplomatic stalemate, and humanitarian suffering.

The territory itself is vast—approximately 266,000 square kilometres, making it roughly the size of the United Kingdom—yet sparsely populated, with an estimated population of around 600,000 people. Its physical geography is dominated by the Sahara Desert, with a 1,110-kilometre Atlantic coastline that provides rich fishing grounds. Beneath its desert surface lie significant phosphate deposits, concentrated in the Bou Craa region, which constitute one of the world’s largest phosphate reserves .

This paper provides a deeply researched analysis of Western Sahara’s economic and political status as of early 2026, drawing upon United Nations Security Council resolutions, diplomatic reporting from Africa Confidential and other authoritative sources, economic data, and analysis of the evolving geopolitical context. The timing is critical: between October 2025 and February 2026, the international community’s stance on Western Sahara’s future has been decisively altered. The UN Security Council’s October 2025 resolution endorsing Morocco’s autonomy plan as the “most feasible solution” represents a fundamental break with decades of UN policy that had prioritised a referendum on self-determination including independence as an option .

The analysis proceeds in three main sections. Section two examines Western Sahara’s economic characteristics, analyzing its resource endowment, the constraints imposed by its disputed status, and the limited available data on economic activity. Section three analyses the political landscape, including the recent diplomatic realignment, the positions of the key parties (Morocco, the Polisario Front, Algeria), and the implications of UN Security Council Resolution 2797. Section four addresses the territory’s regional position, examining its relations with North African neighbours, the role of external powers, and the humanitarian dimension centred on the Tindouf refugee camps. The conclusion synthesizes these findings to assess Western Sahara’s trajectory and the prospects for a definitive resolution.

2. Economic Status: Resource Wealth, Political Constraints, and Unrealized Potential

2.1 The Challenge of Economic Data

Any analysis of Western Sahara’s economy must begin with an acknowledgment of fundamental data limitations. As the territory’s status remains disputed between Morocco (which administers approximately 80 per cent of the territory) and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), proclaimed by the Polisario Front and controlling a smaller eastern zone, comprehensive economic statistics are not collected or published by any single authority .

The “Middle East, North Africa & Central Asia Economic Factbook 2026,” published by ResearchAndMarkets.com, includes Western Sahara alongside 34 other countries and political entities, indicating that sufficient data exists for basic economic characterization, though the source acknowledges the challenges of statistical reporting for disputed territories . The GeoFactbook estimates Western Sahara’s GDP at approximately $1.5 billion, though it notes that “precise figures are difficult to ascertain due to the ongoing dispute over its sovereignty” .

2.2 Phosphate Resources: The Economic Prize

The most significant economic asset of Western Sahara is its phosphate reserves. The Bou Craa mine, located approximately 100 kilometres southeast of El Aaiún (the territory’s largest city), contains vast deposits of high-quality phosphate rock, a critical input for agricultural fertilizer production worldwide. The mine is operated by the Moroccan state-owned company Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP), one of the world’s largest phosphate producers .

The exploitation of these resources has been a source of ongoing controversy. The Polisario Front and human rights organizations have argued that the extraction and export of phosphate from Western Sahara without the consent of the Sahrawi people violates international law, particularly given the UN’s classification of the territory as non-self-governing. A conveyor belt stretching approximately 100 kilometres from the mine to the coast transports the phosphate for export, making it a visible symbol of the economic stakes in the conflict.

The economic significance of the phosphate sector extends beyond Western Sahara itself. OCP is a major contributor to the Moroccan economy, and the Bou Craa reserves enhance Morocco’s position as one of the world’s leading phosphate exporters. For the Polisario Front, control over these resources represents both a potential revenue stream in any future independent state and a point of leverage in diplomatic engagements.

2.3 Fisheries and Maritime Resources

Western Sahara’s 1,110-kilometre Atlantic coastline provides access to some of the world’s richest fishing grounds . The Canary Current upwelling system creates highly productive waters that support diverse marine life, including commercially valuable species such as sardines, cephalopods, and crustaceans. These fisheries have attracted fishing fleets from Europe, particularly Spain, under agreements negotiated with Morocco.

The inclusion of Western Sahara’s waters in EU-Morocco fisheries agreements has been a recurring point of contention. The European Court of Justice has previously ruled that such agreements must not apply to Western Sahara without the consent of the Sahrawi people, leading to complex negotiations over the territorial scope of fisheries partnerships. The Polisario Front has consistently argued that any exploitation of Western Sahara’s maritime resources without Sahrawi consent constitutes a violation of international law.

For Morocco, control over these fisheries represents an important economic asset and a source of leverage in negotiations with the European Union. The 2026 diplomatic realignment, including unified EU support for Morocco’s autonomy plan, may reshape the legal and political framework for fisheries cooperation.

2.4 Agriculture and Traditional Livelihoods

The harsh desert climate of Western Sahara severely limits agricultural potential. Average annual rainfall is less than 200 millimetres, with summer temperatures often exceeding 40°C . These conditions render large-scale rainfed agriculture impossible, and agricultural activity is largely confined to scattered oases where groundwater supports limited cultivation.

The traditional economy of the Sahrawi people was based on nomadic pastoralism, with tribes moving across the vast desert territories in search of grazing for camels and goats. This nomadic lifestyle has been severely disrupted by the conflict, the construction of the Moroccan berm (a defensive sand wall running the length of the territory), and the concentration of population in urban centres and refugee camps.

In areas administered by Morocco, some agricultural development has occurred through investment in water infrastructure and greenhouse cultivation. However, the sector remains small relative to phosphates and fisheries. The SADR-administered areas in the east are even more limited in agricultural potential, with populations relying heavily on humanitarian assistance.

2.5 Informal Economy and Humanitarian Dependence

A significant portion of economic activity in Western Sahara, particularly in the SADR-controlled areas and the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria, operates outside formal statistical reporting. The GeoFactbook notes that Western Sahara has a “largely informal economic system” with many residents engaged in “small-scale trade and services to support their livelihoods” .

The refugee camps near Tindouf, established in 1975-1976 following the Moroccan and Mauritanian occupation of the territory, remain home to an estimated 170,000 Sahrawi refugees. The population of these camps is almost entirely dependent on international humanitarian assistance, primarily coordinated through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the World Food Programme. This dependence creates long-term vulnerabilities and limits economic development in the camps.

The GeoFactbook notes that “despite its economic potential, Western Sahara faces numerous challenges, including political instability, limited infrastructure, and restricted access to international markets” . The ongoing conflict over its status has “hindered foreign investment and development initiatives, creating an environment of uncertainty.”

2.6 Opportunities and Constraints

Looking forward, Western Sahara’s economic potential remains substantial but conditional on political resolution. The phosphate reserves, if developed sustainably and with transparent revenue-sharing arrangements, could generate significant income. The fisheries, if managed responsibly, could provide long-term employment and export earnings. The territory’s desert location and abundant solar radiation could support renewable energy projects, including solar power generation for export.

The GeoFactbook suggests that opportunities exist in “diversifying the economy, particularly through sustainable fishing practices and renewable energy projects” . However, these opportunities cannot be realized without a political framework that provides investment certainty and clarifies ownership of resources. The current diplomatic shift toward recognition of Moroccan sovereignty may, if sustained, unlock investment that has been deferred pending resolution of the status issue.

3. Political Status: The Diplomatic Earthquake of 2025-2026

3.1 The Historical Context: From Referendum to Autonomy

To understand the significance of the October 2025 UN Security Council resolution, it is necessary to recall the historical trajectory of the Western Sahara dispute. When Spain withdrew from the territory in 1975 under the Madrid Accords, it transferred administrative authority to Morocco and Mauritania, bypassing the UN’s decolonization framework. The Polisario Front, which had been formed in 1973 to pursue independence, proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in 1976 and launched an armed struggle against Moroccan and Mauritanian forces.

Mauritania withdrew from the territory in 1979, but Morocco consolidated its control over the phosphate-rich western portion of the territory, constructing a series of defensive berms that effectively partitioned the territory. A UN-brokered ceasefire in 1991 established the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) and provided for a referendum on self-determination in which the Sahrawi people would choose between independence and integration with Morocco.

That referendum never took place. The parties could not agree on voter eligibility criteria, with Morocco seeking to include large numbers of individuals it claimed had tribal ties to the territory, and the Polisario insisting on a census based on Spanish colonial records. The referendum process gradually stalled, and by the early 2000s, the international community began to search for alternative solutions.

In 2007, Morocco presented an autonomy plan to the UN, proposing that Western Sahara would enjoy significant self-governance under Moroccan sovereignty, with local legislative, executive, and judicial authorities elected by residents, while Rabat retained control over defence, foreign affairs, and religious affairs . The Polisario rejected this proposal, insisting on the referendum framework, and the issue remained deadlocked for nearly two decades.

3.2 UN Security Council Resolution 2797: The Diplomatic Shift

The diplomatic landscape was fundamentally transformed on October 31, 2025, when the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2797, endorsing Morocco’s autonomy plan as the basis for resolution of the conflict . The resolution, sponsored by the United States, was adopted by an 11-0 vote, with Russia and China abstaining and Algeria—serving a two-year term on the Council—refusing to participate in the vote.

The resolution’s text represents a decisive break with previous UN language. It states that “genuine autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty could constitute a most feasible solution” to the dispute . Significantly, the resolution makes no mention of a referendum on self-determination that includes independence as an option—the central demand of the Polisario Front and the basis of the UN’s mandate since 1991 .

The resolution also extends MINURSO’s mandate for another year, but its framing of the political process has been fundamentally altered. Instead of working toward a referendum, the UN is now tasked with facilitating negotiations “on the basis of the plan” to reach a mutually acceptable agreement . Staffan de Mistura, the UN Secretary-General’s Personal Envoy for Western Sahara, has been directed to pursue this new framework.

3.3 The Parties: Positions and Reactions

Morocco has greeted the resolution as a historic diplomatic triumph. King Mohammed VI declared that it was “opening a new and victorious chapter in the process of enshrining the Moroccan character of the Sahara, which is intended to bring this issue to a definitive close” . In Rabat, thousands celebrated in the streets, while in Smara, a city in the disputed territory, residents set off fireworks .

Morocco has further solidified its position by releasing initial details of a “revised autonomy plan” that offers greater institutional detail than the 2007 proposal. According to reporting in The Times, the revamped plan outlines the creation of a self-governing Saharan region with its own parliament, government, and courts, while reserving defense, foreign affairs, currency, nationality, and national symbols for the central state . The Moroccan monarch would appoint the head of the autonomous executive, and Rabat would maintain strict limits on regional security forces while retaining influence over major foreign investments and resource-related projects .

The Polisario Front has strongly rejected the resolution. SADR representatives argue that the plan’s provision for the Moroccan monarch to appoint the head of the autonomous executive is incompatible with genuine self-determination . They maintain that the Sahrawi people, as the territory’s legitimate inhabitants, must have the right to choose their own future through a referendum that includes independence as an option.

The Polisario’s diplomatic position has been significantly weakened by the resolution. Having long insisted on the UN’s referendum framework, it now faces an international consensus that has effectively abandoned that framework. Riccardo Fabiani, North Africa director at the International Crisis Group, noted that while the autonomy initiative represents “a major step forward,” the likelihood of resolving the conflict remains low unless the United States finds an imaginative path forward, as self-determination remains a red line for the Polisario .

Algeria emerged as the only party to actively oppose the resolution. Algerian ambassador Amar Bendjama stated that the text “fell short of the expectations and legitimate aspirations of the people of Western Sahara, represented by the Polisario Front [who] have been resisting for over 50 years to have, as the sole party, a say in their own destiny” . Algeria’s refusal to participate in the vote, despite holding a Security Council seat, underscores its deep opposition to the diplomatic shift.

The resolution explicitly identifies Algeria as a main party to the dispute, a designation Algiers has long resisted. Staffan de Mistura has stated that “the parties are clearly identified as Morocco, Polisario, Algeria and Mauritania” . This formal recognition of Algeria’s central role complicates its longstanding position that the conflict is a bilateral matter between Morocco and the Polisario.

Mauritania, the fourth party identified in the resolution, maintains a low-profile position, balancing its relations with Morocco and Algeria while avoiding active involvement in the conflict. Nouakchott participated in Madrid talks facilitated by the UN and US in early 2026 but has not taken a public stance on the autonomy plan.

3.4 International Support: The Consolidating Consensus

Morocco has steadily built international support for its autonomy plan over several years, with the October 2025 resolution representing the culmination of this diplomatic effort. The key breakthrough came in 2020, when President Donald Trump’s administration recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Rabat normalizing relations with Israel . This recognition, maintained and reinforced by subsequent US administrations, fundamentally shifted the diplomatic terrain.

In July 2024, French President Emmanuel Macron also recognized Moroccan sovereignty, following a similar move by the Spanish government in 2022 . The United Kingdom, as a permanent Security Council member, has expressed support for the autonomy plan. Belgium became the latest European country to endorse Morocco’s position in February 2026, joining a growing list that includes the United States, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom, as well as African countries including Ghana and Kenya .

The European Union has moved toward unified support for the autonomy plan. At the Morocco-EU Association Council in early 2026, for the first time all 27 EU member states aligned behind Morocco’s Autonomy Plan as the sole basis for a political resolution, in line with UN Security Council Resolution 2797. This unified position represents a significant diplomatic achievement for Rabat.

Hugh Lovatt, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, notes that there has been “a growing Western shift in backing Morocco’s autonomy proposal as a credible basis for a solution,” though this has not consistently translated into formal recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, with the United States and France as exceptions .

3.5 The Referendum Question: A Vanishing Prospect

The abandonment of the referendum framework represents the most consequential aspect of the diplomatic shift. For three decades, the UN’s position had been that the Sahrawi people must be able to choose their future through a free and fair referendum with independence as an option. Resolution 2797 makes no mention of this framework.

Moroccan officials have long argued that the referendum is impractical. Khalihenna Ould Errachid, chairman of the Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS), stated as early as 2008 that the referendum “has failed, because the distribution of the refugee camps requires a change in borders between Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania and Mali, and no one is willing to cede” . This position has now been effectively adopted by the international community.

The proposed alternative—a referendum on the autonomy plan conducted nationwide in Morocco rather than limited to Western Sahara residents—is unacceptable to the Polisario. Moroccan descriptions stress that the vote would be held nationwide with participation from all Moroccan citizens, which the Polisario argues would deny the Sahrawi people their right to self-determination .

3.6 Human Rights and the Tindouf Camps

The humanitarian dimension of the Western Sahara conflict centres on the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria, where approximately 170,000 Sahrawi refugees have lived since 1975-1976. Conditions in the camps remain difficult, with populations dependent on international humanitarian assistance. The camps are administered by the Polisario Front, which has established a governing structure that includes schools, health facilities, and other basic services.

Human rights organizations have raised concerns about conditions in the camps, including restrictions on freedom of movement and expression. The UNHCR has repeatedly called for a census of the camp populations to facilitate humanitarian planning, a proposal Algeria and the Polisario have resisted. Morocco has argued that the camps are used to sustain the conflict and that their residents should be allowed to return to Western Sahara.

In the territory itself, human rights concerns have been raised regarding the treatment of Sahrawi activists and the management of natural resources. The exploitation of phosphate and fisheries without transparent revenue-sharing has been a recurring point of contention. The diplomatic shift toward recognition of Moroccan sovereignty may reduce international scrutiny of these issues, though human rights organizations continue to monitor the situation.

4. Regional Position: Between the Maghreb Rivalry and Global Geopolitics

4.1 The Morocco-Algeria Rivalry

Western Sahara remains the central axis of the deep rivalry between Morocco and Algeria, the two dominant powers of the Maghreb. Algeria’s support for the Polisario Front—providing diplomatic backing, military supplies, and sanctuary for the refugee camps—has been a constant since the conflict’s inception. Morocco’s claim to the territory is a core element of national identity and a source of regime legitimacy.

The October 2025 resolution has intensified this rivalry. Algeria’s isolation on the Security Council vote—the only opposing voice—underscores its diplomatic defeat. Yet Algiers retains significant capacity to complicate Moroccan interests. Its hydrocarbon wealth, military capabilities, and regional influence ensure that the conflict cannot be resolved without Algerian acquiescence.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has offered to facilitate talks between Morocco and Algeria on Western Sahara’s future, suggesting a US move to push for the end of MINURSO . Such talks would represent a significant development, as Algeria has historically resisted direct bilateral negotiations, insisting that the conflict is between Morocco and the Polisario.

4.2 The United States: From Neutrality to Partisanship

The United States has moved decisively from its traditional position of neutrality to active support for Morocco’s claim. President Trump’s 2020 recognition of Moroccan sovereignty marked the first time any major power had taken this step. The Biden administration maintained the policy, and the Trump administration’s second term has reinforced it.

At the April 2025 meeting between Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita and US officials, Secretary Rubio referred to Morocco’s “Autonomy Proposal as the only framework” for resolution and urged parties to “negotiate a mutually acceptable solution” . Senior State Department official Lisa Kenna has stated that “genuine autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty” is the “only feasible solution” .

This US position has been critical to the diplomatic shift. As the permanent member with greatest influence on Security Council outcomes, Washington’s sponsorship of Resolution 2797 ensured its adoption. The US has also engaged in direct diplomacy, hosting discreet meetings in Washington involving envoys from Morocco, Algeria, and the Polisario Front .

4.3 European Powers: Alignment and Divergence

European powers have increasingly aligned with Morocco’s position, though with variations in the degree of support. France’s formal recognition of Moroccan sovereignty under President Macron in July 2024 was a significant breakthrough, following Spain’s shift in 2022. The United Kingdom has expressed support for the autonomy plan as a credible basis for resolution.

Germany has moved toward the Moroccan position but has not formally recognized sovereignty. The unified EU stance at the February 2026 Association Council represents a significant diplomatic achievement, though individual member states maintain distinct positions.

This European alignment reflects multiple factors: energy cooperation with Morocco (and Algeria’s complicated relationship with Europe), migration management, counterterrorism partnerships, and economic interests. The Polisario Front’s traditional support in European civil society and some left-wing parties has not translated into sustained diplomatic backing.

4.4 The African Dimension

Within the African Union, the Western Sahara issue remains divisive. The SADR is a full member of the African Union, a status that Morocco long opposed and that contributed to its decades-long withdrawal from the organization. Morocco rejoined the AU in 2017 while maintaining its claim to Western Sahara, creating an anomalous situation in which two members have overlapping territorial claims.

A growing number of African countries, including Ghana and Kenya, have expressed support for Morocco’s autonomy plan . This shift reflects Morocco’s active diplomatic engagement across the continent, including economic investments, religious diplomacy, and political outreach. However, the African Union has not taken a unified position, and the SADR retains recognition from several African states.

4.5 The Israel Factor

The normalization of relations between Morocco and Israel in 2020, in exchange for US recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, introduced a new dimension to the conflict . Morocco has since deepened its security and economic partnership with Israel, including the January 2026 Military Action Plan, which positions Morocco as Israel’s primary security partner in North Africa.

This alignment has implications for Western Sahara. It reinforces Morocco’s strategic value to the United States, which brokered the normalization agreement. It also complicates Algeria’s position, as Algiers maintains closer ties with Iran and Russia. The Israel-Morocco axis may provide Rabat with enhanced military and intelligence capabilities relevant to the Western Sahara theater.

4.6 The Future of MINURSO

The UN peacekeeping mission in Western Sahara, MINURSO, has been extended for another year under Resolution 2797 . However, its future is increasingly uncertain. Established in 1991 to monitor the ceasefire and prepare for the referendum, MINURSO’s mandate has become anachronistic now that the referendum framework has been abandoned.

US officials have hinted at moves to push for MINURSO’s termination . Such a step would be strongly opposed by Algeria and the Polisario, who view the mission as providing essential monitoring and international presence. Morocco has historically viewed MINURSO with suspicion, arguing that its mandate should be revised to reflect the new diplomatic reality.

The practical implications of MINURSO’s potential withdrawal would be significant. The mission provides a buffer between Moroccan and Polisario forces along the berm, and its departure could increase the risk of resumed hostilities. However, the diplomatic shift toward autonomy may render the mission’s original purpose obsolete.

5. Conclusion: Western Sahara’s Trajectory and Unresolved Questions

Western Sahara in early 2026 stands at a crossroads. The October 2025 UN Security Council resolution endorsing Morocco’s autonomy plan represents the most significant diplomatic development in the conflict’s five-decade history. The long-standing framework of a referendum on self-determination has been effectively abandoned, replaced by a process aimed at implementing autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty.

This shift reflects Morocco’s successful diplomatic strategy, built on its geostrategic value to Western powers, its normalization with Israel, and its economic engagement across Africa and Europe. The United States, France, Spain, and a growing list of other countries have aligned with Rabat’s position, while Algeria and the Polisario Front have been diplomatically isolated.

Yet fundamental questions remain unresolved. The Polisario Front continues to reject the autonomy framework, insisting on the right to self-determination. The Sahrawi refugees in Tindouf—numbering approximately 170,000—remain in camps, their future uncertain. The exploitation of phosphate and fisheries resources without transparent revenue-sharing continues to generate controversy. Human rights concerns regarding Sahrawi activists and conditions in the camps persist.

The economic potential of Western Sahara—its phosphate deposits, fisheries, and renewable energy possibilities—cannot be fully realized without a definitive resolution. The current diplomatic shift may, if sustained, unlock investment and development that have been deferred by decades of uncertainty. But such development will remain contested unless it addresses the legitimate interests of the Sahrawi people.

Riccardo Fabiani’s assessment captures the essential tension: the autonomy initiative is “a major step forward,” yet the likelihood of resolution remains low unless the United States finds an imaginative path forward, as self-determination remains a red line for the Polisario . Zaid M. Belbagi, an adviser close to Rabat’s government, describes recent developments as a “paradigm shift” in how the Kingdom views its relationship with its neighbours .

Whether that paradigm shift can produce a definitive resolution—one that is accepted by all parties and that provides for the rights and aspirations of the Sahrawi people—remains the central question. Western Sahara’s trajectory will be shaped by the evolution of US policy, the depth of European alignment, the capacity of Algerian diplomacy to recover from its isolation, and the resilience of the Polisario Front in the face of mounting diplomatic pressure. The territory’s people, whose fate has been contested for five decades, await an answer.

References

-

ResearchAndMarkets.com. (2026, February 10). “Middle East, North Africa & Central Asia Economic Factbook 2026.” https://au.finance.yahoo.com/news/middle-east-north-africa-central-161300244.html

-

Africa Confidential. (2026, February 17). “UNSC changes tack, backs Morocco’s semi-autonomy plan.” https://www.africa-confidential.com/article/id/15708/

-

New Age BD. (2026, February 16). “UN backs Morocco plan for W Sahara autonomy.” https://www.newagebd.net/post/africa/280857/

-

GeoFactbook. (2026). “Western Sahara: Population, GDP, Map & Key Facts (2026).” https://geofactbook.com/countries/western-sahara

-

Africa Confidential. (2026, February 16). “Washington backs Rabat on Western Sahara, setting up clash with UN mission on territory’s sovereignty.” https://www.africa-confidential.com:443/index.aspx?pageid=7&articleid=15438

-

Assahifa. (2026, February 15). “The Times: U.S. Prioritizes Western Sahara Resolution, Morocco’s New Autonomy Plan a Major Step Forward.” https://www.assahifa.com/english/africa/the-times-u-s-prioritizes-western-sahara-resolution-moroccos-new-autonomy-plan-a-major-step-forward/

-

APAnews. (2026, February 10). “Western Sahara talks: UN clarifies Algeria’s key role.” https://apanews.net/western-sahara-talks-un-clarifies-algerias-key-role/

-

Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS). (2008, February 8). “Corcas is preparing an autonomy for the Sahara inspired by Spain.” http://corcas.com/Default.aspx?ItemID=5003&ctl=Details&mid=1508&tabid=708

Related Posts

The Economic and Political Status of Rwanda in East Africa

Abstract This paper examines Rwanda's contemporary economic and political status…

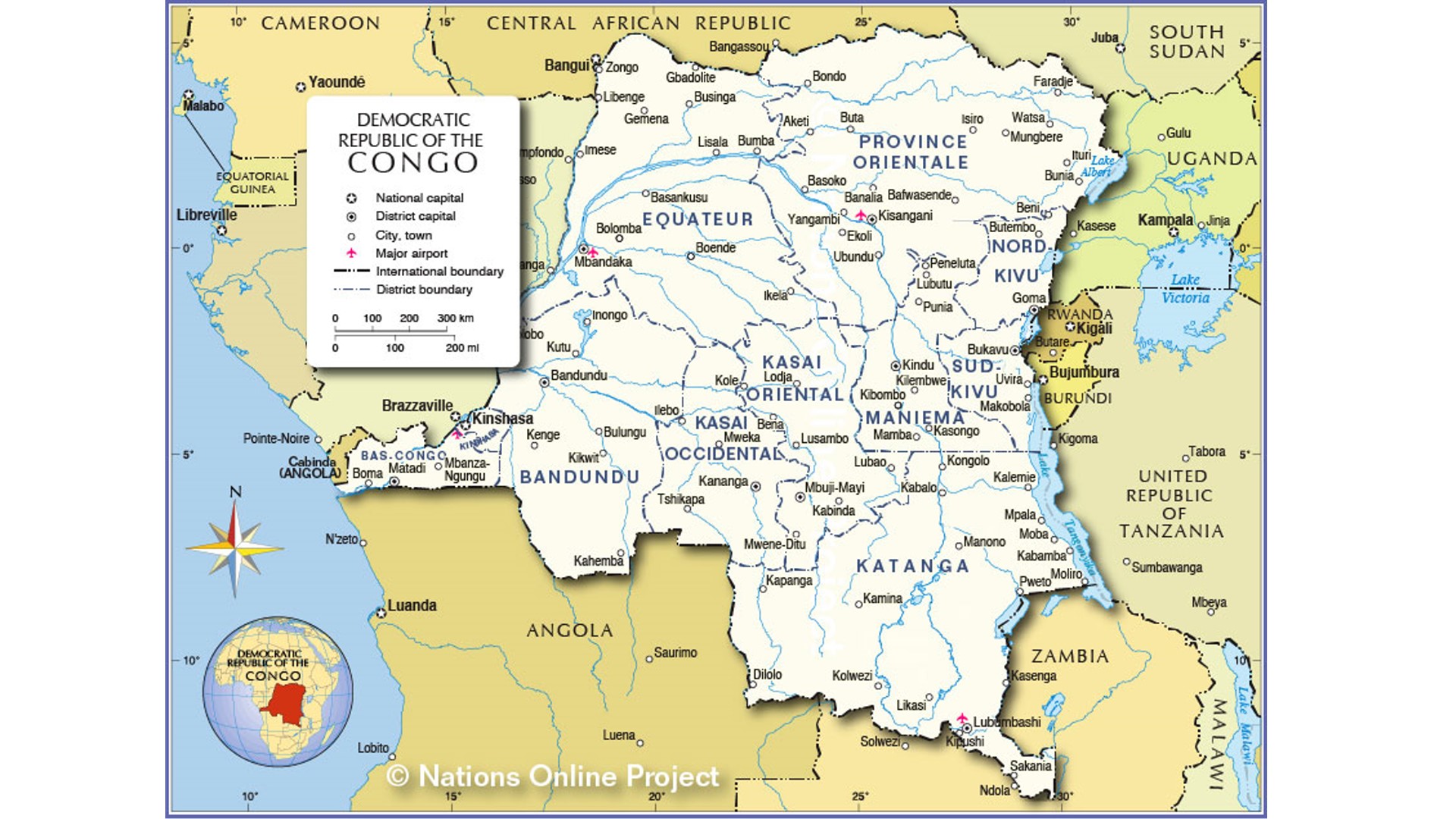

Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Economic and Political Status Analysis

Abstract This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the Democratic…

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

Introduction: A Historic Gambit The African Continental Free Trade Area…