Abstract

This paper examines Lesotho’s economic and political status within Southern Africa, arguing that the kingdom occupies a paradoxical position of strategic significance and structural vulnerability. As the region’s “water tower,” Lesotho possesses a resource upon which South Africa’s economic heartland depends, yet it remains one of Africa’s most import-dependent economies with limited productive capacity. Drawing on recent economic data, diplomatic developments, and regional security analyses through February 2026, the analysis demonstrates how Lesotho navigates profound asymmetries through infrastructure diplomacy, multilateral engagement, and strategic partnership diversification. The paper contends that Lesotho’s status in Southern Africa is best understood through three interconnected dimensions: as an indispensable water and energy partner through the Lesotho Highlands Water Project; as a politically fragile state managing coalition governance, youth unemployment crises, and security sector reform; and as an increasingly assertive diplomatic actor pursuing continental leadership through AU Peace and Security Council membership and regional infrastructure initiatives. The convergence of water security imperatives, political transition challenges, and new diplomatic opportunities creates both constraints and possibilities for Lesotho’s regional positioning.

Keywords: Lesotho-South Africa relations, water security, regional integration, import dependency, coalition governance, SADC infrastructure development

Introduction

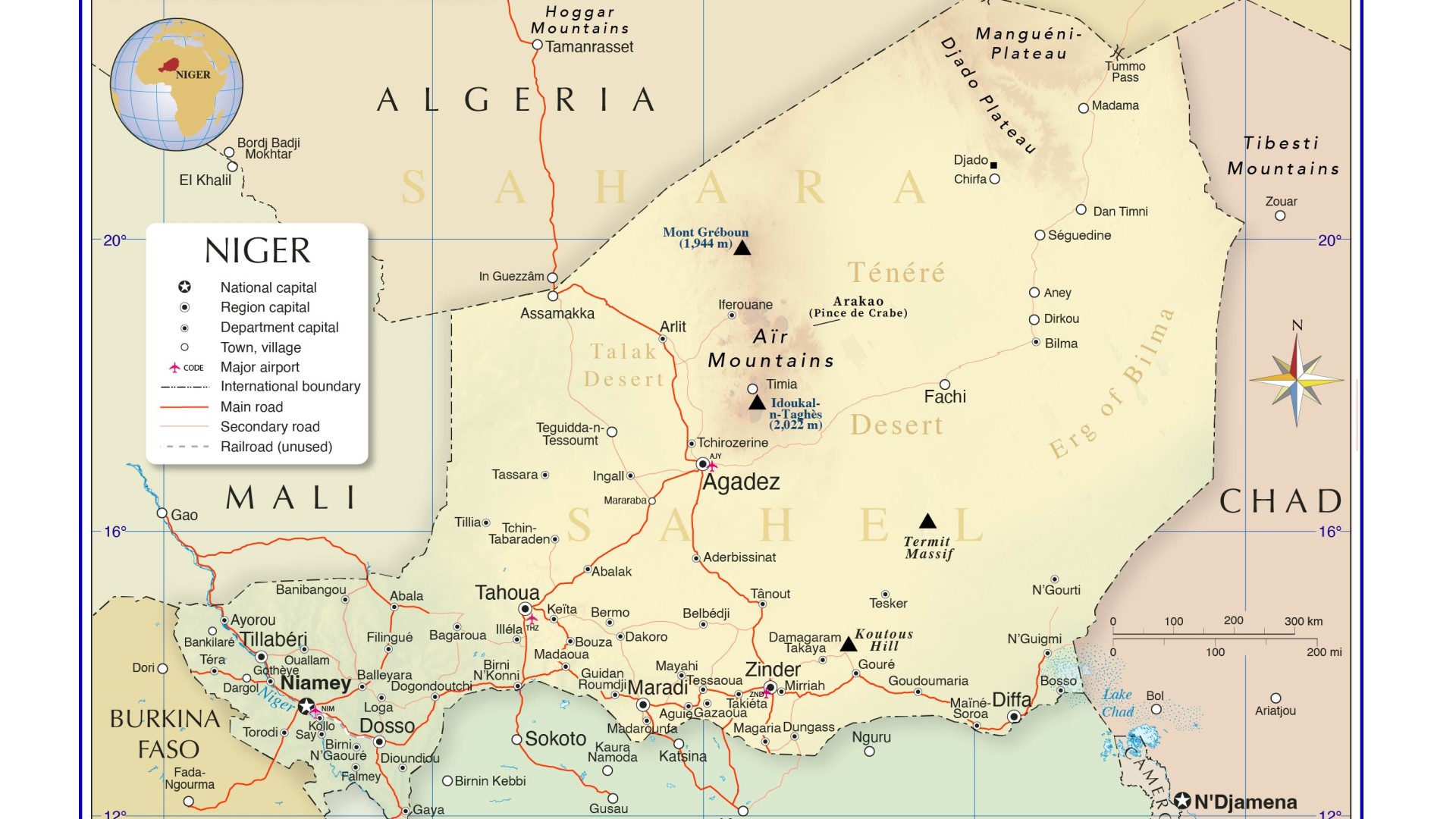

The Kingdom of Lesotho occupies a distinctive position in Southern African international relations. Entirely surrounded by South Africa, the mountainous kingdom is simultaneously one of the region’s most strategically significant states—as the source of vital water supplies for Gauteng, South Africa’s industrial heartland—and one of its most economically vulnerable, with imports equivalent to approximately 99 percent of GDP . This fundamental paradox shapes every dimension of Lesotho’s engagement with its neighbors and the broader region.

This paper investigates a central research question: What is Lesotho’s current economic and political status within Southern Africa, and how does the kingdom navigate the profound asymmetries between its strategic water endowment and its structural economic vulnerabilities? The significance of this inquiry extends beyond bilateral relations with South Africa. Lesotho’s trajectory illuminates broader dynamics of small state survival in asymmetric regional relationships, the potential for resource endowments to generate development leverage, and the tensions between political fragility and diplomatic ambition in Southern African governance.

This paper proceeds in five sections. Following this introduction, Section Two examines Lesotho’s domestic political economy, establishing the foundational context for its external relations. Section Three analyzes the cornerstone of Lesotho’s regional economic position: the Lesotho Highlands Water Project and its expansion. Section Four investigates trade integration and structural vulnerabilities, including SACU membership and import dependency. Section Five addresses political and diplomatic engagement, including Lesotho’s election to the AU Peace and Security Council and its role in regional infrastructure initiatives. The conclusion synthesizes these findings and offers prospective analysis.

1. Lesotho’s Domestic Political Economy: Fragility, Reform, and the Youth Challenge

Lesotho’s external status in Southern Africa cannot be understood without first examining its domestic political and economic trajectory. The kingdom’s internal dynamics—characterized by coalition governance fragility, persistent unemployment, and ongoing reform efforts—fundamentally condition its capacity to leverage regional opportunities.

1.1 Political Landscape: Coalition Governance and Institutional Challenges

Lesotho has experienced significant political turbulence over the past decade, with multiple coalition governments struggling to maintain stability. The current administration, led by Prime Minister Sam Matekane’s Revolution for Prosperity party, governs through a coalition arrangement that reflects the fragmented character of Basotho politics. This fragmentation has complicated efforts to implement coherent policy agendas and sustain reform momentum.

The political landscape is characterized by persistent institutional challenges. Government remains the largest employer, a pattern made problematic by corruption concerns and bureaucratic inefficiency . International observers have repeatedly noted governance weaknesses that constrain development effectiveness and deter private investment. The African Development Bank and other development partners have emphasized the need for institutional strengthening as a precondition for sustained poverty reduction and economic transformation.

Security sector reform remains an ongoing priority following years of instability that damaged Lesotho’s international reputation. Progress in professionalizing the military and police services has been made, but concerns persist about the potential for political interference in security institutions—a vulnerability that affects investor confidence and regional perceptions of Lesotho’s stability.

1.2 The Youth Unemployment Crisis

The most pressing domestic challenge facing Lesotho is the youth unemployment crisis, which has reached levels that threaten social cohesion and political stability. With approximately 310,000 unemployed youth in a country of just over 2 million people, the scale of the crisis is extraordinary . The unemployment rate stands at approximately 30.1 percent overall, with youth unemployment significantly higher .

In July 2025, Prime Minister Matekane declared youth unemployment a national disaster at the National Youth Dialogue, announcing that the government would facilitate the creation of more than 62,000 jobs as part of the national response . This declaration was intended to signal urgency and mobilize extraordinary action. However, implementation has lagged dramatically.

The Coalition of Youth Organizations has sharply criticized the government for failing to deliver on its commitments. In February 2026, the coalition expressed “deep concern and disappointment” at the Prime Minister’s remarks suggesting that “creating jobs is difficult and that the government cannot create employment for all young people” . The coalition argued that these statements “directly contradict the spirit and commitment of the government’s own declaration of youth unemployment as a national disaster.”

The coalition’s statement emphasized that the 62,000-job pledge “was already the bare minimum, given that Lesotho has more than 310,000 unemployed youth. Even if fully implemented, the promise would address only a small portion of those affected” . This critique highlights the profound gap between political rhetoric and delivery capacity.

The implications of this crisis for Lesotho’s regional status are significant. A government struggling to meet basic employment expectations domestically has limited bandwidth for proactive foreign policy engagement. Moreover, continued failure on youth employment risks generating social unrest that could require regional intervention, as occurred during previous periods of instability. The coalition explicitly warned that “youth unemployment remains one of the greatest threats to national stability, economic growth and social cohesion” .

1.3 Economic Structure and Development Constraints

Lesotho’s economy exhibits structural characteristics that constrain growth and employment generation. The country has few natural resources beyond water, with agriculture and livestock providing livelihoods for the largely rural population . The local market is too small to sustain a lucrative domestic market for investors, and tourism has not yet been developed to its fullest potential .

The service sector has grown significantly, contributing approximately half of economic activity and employing 58.8 percent of the workforce . Manufacturing contributes around 22 percent of GDP, with textile and apparel production strengthened by preferential access to United States markets under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) . This sector represents one of Lesotho’s few success stories in export-oriented industrialization, though it remains vulnerable to shifts in US trade policy and competition from lower-cost producers.

Despite these pockets of dynamism, the fundamental constraint remains limited productive capacity. Lesotho’s import dependence—with imports representing approximately 99 percent of GDP—reflects the economy’s inability to produce basic consumer and industrial goods domestically . This structural trade imbalance is sustainable only because of SACU revenue transfers, worker remittances, and development assistance, each of which carries its own vulnerabilities.

GDP growth reached 2.6 percent in FY24/25, though projections for FY25/26 have been revised downward to 1.4 percent due to external shocks . This modest growth rate is insufficient to generate the jobs needed for a young and growing population, perpetuating the employment crisis and associated social pressures.

1.4 The National Strategic Development Plan

The government has articulated its development vision through the National Strategic Development Plan 2023/24-2027/28, which prioritizes water security, climate resilience, and regional integration . This framework recognizes that Lesotho’s future prosperity depends heavily on leveraging its strategic water endowment while building greater resilience to climate shocks that increasingly threaten agricultural livelihoods.

The plan’s emphasis on regional integration reflects realistic assessment of Lesotho’s structural position. With a small domestic market and limited natural resources, growth must come through deeper integration with neighboring economies—particularly South Africa—and through infrastructure investments that enhance Lesotho’s role in regional value chains. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project Phase II represents the most significant manifestation of this strategy.

2. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project: Cornerstone of Regional Integration

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) constitutes the foundation of Lesotho’s economic relationship with South Africa and its strategic significance within Southern Africa. This massive infrastructure initiative transfers water from Lesotho’s highlands to South Africa’s industrial heartland while generating hydroelectric power and royalty revenues for Lesotho.

2.1 Project Overview and Strategic Importance

The LHWP is one of Africa’s largest and most successful transboundary water infrastructure projects. Through a system of dams and tunnels, water from Lesotho’s highland rivers is transferred to South Africa’s Vaal River system, supplying water to Gauteng—the industrial and population core of the South African economy. For Lesotho, the project generates royalty payments that constitute a significant revenue stream, while the associated hydroelectric facilities contribute to domestic electricity supply.

South African municipalities are critically dependent on Lesotho’s water, making the project a matter of national security for the region’s dominant economy . This dependency creates structural leverage for Lesotho that partially offsets the broader asymmetries in bilateral relations. The water relationship ensures that South Africa maintains fundamental interest in Lesotho’s stability and functional governance.

2.2 Phase II Expansion and Investment Opportunities

Phase II of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project is currently underway, offering significant infrastructure investment opportunities and long-term revenue potential for Lesotho . This expansion will increase water transfer capacity and includes construction of the Polihali Dam and associated tunnels, representing billions of dollars in infrastructure investment.

The project creates multiple economic benefits for Lesotho beyond direct royalties. Construction employment generates income for Basotho workers, while improved infrastructure enhances connectivity in remote areas. The expanded water transfer capacity will secure Lesotho’s revenue stream for decades, providing fiscal predictability that supports long-term planning.

For South Africa, Phase II is equally critical. Gauteng’s continued growth and industrialization depend on reliable water supplies that the expanded project will help secure. The mutual dependency created by the project—South Africa needing water, Lesotho needing revenue and investment—establishes a foundation for sustained bilateral cooperation even when political relations face strain.

2.3 Environmental and Climate Considerations

Climate change introduces new complexities to the LHWP framework. Global warming has increased the incidence and severity of drought, particularly impacting grazing lands and potentially affecting water availability in Lesotho’s highlands . These climate risks create shared vulnerability: reduced rainfall affects both Lesotho’s agricultural livelihoods and the water volumes available for transfer to South Africa.

The National Strategic Development Plan’s emphasis on climate resilience reflects recognition that the water resource upon which Lesotho’s regional significance rests is itself vulnerable to climate variability. Investments in catchment management, watershed protection, and climate monitoring are essential to preserve the value of the LHWP infrastructure and ensure continued water flows.

Toxic run-off from mining operations also poses potential threats to water quality, jeopardizing Lesotho’s primary export if not properly managed . This concern highlights the need for coordinated environmental regulation across sectors and borders, as mining impacts in one location can affect water quality throughout the system.

2.4 Beyond Water: The Lesotho-Botswana Water Transfer Project

A significant new dimension of Lesotho’s water diplomacy emerged in February 2026, when the Southern African Development Community approved US$1.83 million to advance the Lesotho-Botswana Water Transfer Project . This major initiative is designed to secure long-term water supplies in Botswana and South Africa by channeling water from Lesotho’s highlands through South Africa to Botswana.

The funding, released through the SADC Project Preparation and Development Facility (PPDF), will finance a full Environmental and Social Impact Assessment and a comprehensive feasibility study for the 700-kilometre scheme . The PPDF is part of the SADC–German cooperation framework, funded by the German government and jointly implemented by KfW and the Development Bank of Southern Africa.

This project represents a significant expansion of Lesotho’s water export footprint. While the LHWP focuses on supplying South Africa, the Botswana transfer project would extend Lesotho’s water reach to an additional SADC member state, diversifying Lesotho’s water customers and deepening its regional integration. The project is expected to “ease Botswana’s rising water demand while generating economic, energy and food‑security benefits for Lesotho, South Africa and the wider region” .

For Lesotho, this initiative offers potential to expand royalty revenues and enhance its status as the region’s water security anchor. For SADC, it represents an important step toward regional infrastructure integration and collective resource management.

3. Trade Integration and Structural Vulnerabilities: SACU, Import Dependency, and Export Development

Beyond water, Lesotho’s economic relationship with Southern Africa is defined by deep trade integration through the Southern African Customs Union and persistent structural vulnerabilities arising from import dependency.

3.1 SACU Membership: Benefits and Constraints

Lesotho is a founding member of the Southern African Customs Union, one of the oldest customs unions in the world. SACU membership provides Lesotho with duty-free access to regional markets, including South Africa’s large and diversified economy. This access is particularly important for Lesotho’s textile and apparel sector, which depends on both regional supply chains and preferential access to developed country markets.

The SACU revenue-sharing formula, which favors smaller economies, makes transfers a critical component of Lesotho’s fiscal position. While exact figures for Lesotho’s SACU receipts are not detailed in available sources, the pattern observed in neighboring Eswatini—where SACU accounts for approximately 45 percent of government revenues—suggests comparable dependency . This fiscal reliance creates vulnerability to fluctuations in regional trade volumes and external tariff policy.

SACU membership also constrains Lesotho’s trade policy autonomy. As a member of a customs union with a common external tariff, Lesotho cannot independently negotiate trade agreements with external partners. All trade negotiations must be conducted at the SACU level, with South Africa playing the dominant role in shaping regional positions. This constraint became evident in discussions regarding a potential SACU-China free trade agreement, where Eswatini’s diplomatic relations with Taiwan created complications for the entire bloc .

3.2 Extreme Import Dependency: Structural Implications

Recent analysis identifies Lesotho as one of Africa’s most import-dependent economies, with imports representing approximately 99 percent of GDP . This extraordinary figure underscores the limited domestic productive capacity and deep integration with South African supply chains for consumer and industrial goods.

The import dependency reflects multiple structural factors: small market size limiting opportunities for import-substituting industrialization; proximity to South Africa’s highly developed manufacturing sector; and the legacy of policy choices that have not prioritized domestic productive capacity building. The result is an economy highly sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations, transport costs, and supply chain disruptions originating in South Africa.

Through the Common Monetary Area arrangement, Lesotho’s currency is pegged at par with the South African Rand, which also circulates freely as legal tender. This monetary integration provides stability and eliminates exchange rate risk in bilateral trade, but it transmits South African economic conditions directly into Lesotho regardless of domestic circumstances. When South Africa faces inflation, interest rate adjustments, or growth slowdowns, Lesotho experiences parallel effects without independent monetary policy tools to cushion the impact.

3.3 Textile and Apparel Sector: AGOA and Export Competitiveness

The textile and apparel sector represents Lesotho’s most significant manufactured export industry. Benefiting from preferential access to United States markets under AGOA, the sector employs tens of thousands of workers, primarily women, and generates substantial export earnings. Manufacturing contributes approximately 22 percent of GDP, with textiles accounting for a significant share .

The sector’s competitiveness depends on continued preferential access to US markets, which faces periodic uncertainty as AGOA renewal debates occur in Washington. Any erosion of this access would have severe employment consequences, given the sector’s labor intensity and limited alternative markets. Regional integration through SACU provides some diversification of market access, but the US market remains critical.

The sector also depends on regional value chains, with fabric and inputs often sourced from South Africa or imported through regional ports. This integration means that logistics performance in South Africa directly affects Lesotho’s export competitiveness. Port efficiency, transport costs, and border procedures all influence the sector’s viability.

3.4 Remittances and Labor Migration

Worker remittances from Basotho employed in South Africa have historically provided a significant source of income for rural households. While employment patterns have shifted over time—with declines in formal mine labor and growth in other sectors—remittances continue to offset poverty and support consumption.

The importance of remittances underscores Lesotho’s deep human integration with South Africa. Extended family networks span the border, and labor migration remains a fundamental feature of Basotho life. This human connectivity creates social stakes in bilateral relations that complement economic and political dimensions.

4. Political and Diplomatic Engagement: Assertive Multilateralism and Regional Leadership

Recent developments reveal an increasingly assertive Lesotho foreign policy, pursuing continental leadership roles and active participation in regional initiatives despite domestic constraints.

4.1 AU Peace and Security Council Membership

In February 2026, Lesotho achieved a significant diplomatic success with its election to the African Union Peace and Security Council for the 2026–2028 term . Lesotho was elected alongside South Africa to represent the Southern African region, marking recognition of its diplomatic engagement and commitment to continental peace and security architecture.

The candidature submission reflected Lesotho’s “principled and consistent approach to issues of peace and security,” with Foreign Minister Lejone Mpotjoana stating that the country “stands ready to serve and contribute meaningfully to the continent’s stability” . He emphasized Lesotho’s “firm belief in multilateralism, dialogue and preventive diplomacy as critical tools in addressing conflicts and sustaining peace in Africa.”

This election carries multiple implications for Lesotho’s regional status. First, it provides a platform for Lesotho to shape continental security discussions and demonstrate diplomatic capability beyond its size. Second, it aligns Lesotho with South Africa in representing Southern African interests, reinforcing bilateral coordination. Third, it signals that regional peers view Lesotho as a constructive partner despite domestic challenges.

The Peace and Security Council is the AU’s standing decision-making organ for conflict prevention, management, and resolution. Serving on this body will require Lesotho to engage with complex continental crises, from Sahel insurgencies to Eastern Congo instability. This engagement offers opportunities for capacity building and diplomatic profile enhancement, but also demands resources and attention that a small foreign ministry must carefully allocate.

4.2 The AFCON 2028 Bid: Infrastructure Diplomacy

Lesotho has also pursued regional cooperation through sports diplomacy, formally expressing interest in joining the Southern African joint bid to co-host the 2028 Africa Cup of Nations . The bid, spearheaded by South Africa alongside Namibia and Botswana, would see matches distributed across multiple countries, with Lesotho seeking inclusion as an additional host.

This ambition confronts significant infrastructure constraints. Lesotho’s primary venue, Setsoto Stadium, has been barred from hosting international fixtures since 2021 for failing to meet Confederation of African Football standards . The ban has forced Lesotho’s national team to play “home” matches in South Africa, highlighting the infrastructure deficit.

Minister of Tourism, Sports, Arts and Culture Motlatsi Maqelepo acknowledged these challenges but argued that a successful AFCON bid could serve as “the necessary catalyst to overhaul the nation’s sporting facilities” . He confirmed that “processes to upgrade Setsoto Stadium were already underway” and expressed hope that within two years the upgrade would be complete .

The AFCON bid illustrates a broader pattern in Lesotho’s regional engagement: leveraging multilateral initiatives to drive domestic investment and reform. By committing to co-hosting, Lesotho creates external pressure and accountability for infrastructure development that might otherwise lack political momentum. The strategy carries risks—failure to deliver could generate embarrassment—but also potential rewards in accelerated modernization.

4.3 Coalition Diplomacy: Managing Relations with South Africa

Lesotho’s relationship with South Africa requires continuous diplomatic attention given the profound asymmetries and multiple points of interaction. The bilateral agenda encompasses water management, trade facilitation, labor migration, security cooperation, and political consultation. Managing this complex relationship demands skilled diplomacy and institutional capacity.

The personal dynamics between Prime Minister Matekane and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa matter for bilateral engagement. Both leaders represent new political formations—Matekane’s Revolution for Prosperity disrupting established patterns, Ramaphosa navigating coalition governance following ANC decline. This shared experience of political transition creates potential for mutual understanding.

Regular bilateral consultations occur through multiple channels: the Binational Commission, sectoral working groups, and direct presidential engagement. These mechanisms provide continuity beyond individual leaders and enable problem-solving before issues escalate to crises. The water relationship, in particular, benefits from well-established institutional frameworks that depoliticize technical cooperation.

4.4 SADC Engagement and Regional Infrastructure

Beyond bilateral relations, Lesotho participates actively in Southern African Development Community structures and initiatives. The Lesotho-Botswana Water Transfer Project, advanced with SADC support, exemplifies Lesotho’s engagement with regional infrastructure planning . By participating in SADC-facilitated projects, Lesotho gains access to technical assistance and financing that might otherwise be unavailable.

SADC engagement also provides platforms for Lesotho to coordinate positions with neighboring states on issues ranging from trade policy to security cooperation. The organization’s consensus-based decision-making gives smaller states voice in regional affairs, partially offsetting the power asymmetries that characterize bilateral relations with South Africa.

5. Comparative Positioning: Lesotho in Regional Context

Understanding Lesotho’s status in Southern Africa requires comparative perspective on its position relative to neighboring states and regional patterns.

5.1 Economic Asymmetries and Complementarities

Lesotho’s economy is dwarfed by South Africa’s, creating fundamental asymmetry in bilateral relations. South Africa’s GDP exceeds Lesotho’s by a factor of approximately 200, and its diversified industrial base dominates regional production structures. This asymmetry conditions every dimension of economic engagement, from trade patterns to investment flows to monetary policy.

Yet complementarities also exist. Lesotho’s water endowment provides a resource South Africa urgently needs and cannot source elsewhere at comparable cost. The LHWP creates mutual dependency that partially balances structural asymmetries. South Africa’s need for Lesotho’s water ensures sustained attention to Lesotho’s stability and functional governance.

The textile and apparel sector illustrates both integration and vulnerability. Lesotho’s preferential access to US markets under AGOA provides export opportunities, but production depends on South African inputs and transport infrastructure. This interdependence means that performance in both countries affects sector outcomes.

5.2 Demographic and Geographic Factors

Lesotho’s population of approximately 2.2 million is small by regional standards, limiting domestic market size and constraining opportunities for import-substituting industrialization. Geographic isolation—the kingdom is entirely surrounded by South Africa—creates transport dependence and limits options for trade route diversification.

However, Lesotho’s mountainous terrain provides the altitudinal gradient that makes water transfer feasible and cost-effective. This geographic endowment is the foundation of Lesotho’s strategic significance. The highlands capture precipitation that flows toward South Africa’s industrial heartland, creating natural comparative advantage in water exports.

5.3 Governance Patterns: Similarities and Differences

Lesotho’s governance challenges—coalition instability, corruption concerns, youth unemployment—reflect broader Southern African patterns. Across the region, liberation-era parties have lost dominance, coalition governance has become more common, and youth unemployment has emerged as a defining political issue. Lesotho’s experience thus resonates with regional trends while manifesting distinctive features.

The kingdom’s constitutional monarchy adds a dimension absent in most regional states. While the monarchy’s political role has diminished over time, traditional institutions retain cultural significance and local authority. This hybrid system—combining modern constitutional structures with traditional governance—creates distinctive political dynamics that external partners must understand.

5.4 Comparison with Eswatini: Parallels and Contrasts

Lesotho and Eswatini share characteristics as small, landlocked monarchies surrounded by South Africa. Both depend heavily on SACU revenues, experience high unemployment, and maintain deep integration with the South African economy. Both face challenges of diversifying beyond historical economic patterns.

However, significant differences exist. Eswatini remains an absolute monarchy with banned political parties, while Lesotho operates as a constitutional monarchy with multiparty competition. This governance divergence affects international perceptions and partnership opportunities. Lesotho’s democratic system aligns more closely with regional norms, facilitating diplomatic engagement and development cooperation.

The two countries’ resource endowments also differ. Lesotho’s water resources provide strategic leverage and revenue streams that Eswatini lacks. This endowment enables Lesotho to pursue infrastructure-based development strategies not available to its neighbor.

Conclusion: Lesotho’s Evolving Status and Future Trajectories

This paper has examined Lesotho’s economic and political status within Southern Africa across multiple dimensions: domestic political economy foundations, water infrastructure diplomacy, trade integration and vulnerabilities, and assertive multilateral engagement. The analysis reveals a kingdom navigating fundamental paradoxes—strategic significance combined with structural vulnerability, diplomatic ambition alongside domestic fragility, resource wealth amid limited productive capacity.

Lesotho’s status in Southern Africa is best understood through three interconnected dimensions: as an indispensable water and energy partner through the Lesotho Highlands Water Project and emerging regional water transfer initiatives; as a politically fragile state managing coalition governance, youth unemployment crises, and ongoing reform efforts; and as an increasingly assertive diplomatic actor pursuing continental leadership through AU Peace and Security Council membership and regional infrastructure diplomacy.

Several factors will shape the future trajectory of Lesotho’s regional position.

First, water diplomacy outcomes will remain foundational. Successful implementation of LHWP Phase II and advancement of the Lesotho-Botswana Water Transfer Project would enhance Lesotho’s revenue streams and strategic significance. Conversely, climate-related water variability or quality degradation would undermine this core asset. Continued investment in catchment protection and climate resilience is essential.

Second, domestic stability and governance performance will affect Lesotho’s capacity to leverage external opportunities. The youth unemployment crisis poses existential risks: continued failure to generate employment could trigger social unrest requiring regional intervention, damaging Lesotho’s international reputation and diverting attention from diplomatic engagement. Implementation of the 62,000-job pledge and credible employment strategies are necessary to maintain domestic peace and external confidence.

Third, political transition management will influence investor perceptions and development partner engagement. Coalition governance requires sustained negotiation and compromise; breakdown could precipitate early elections or prolonged instability. Building institutional capacity beyond personalities and parties is essential for long-term stability.

Fourth, regional integration dynamics will shape opportunity structures. Deeper SADC infrastructure coordination, AfCFTA implementation, and potential SACU external agreements will affect Lesotho’s trade and investment environment. Active participation in shaping these frameworks is necessary to ensure Lesotho’s interests are reflected.

The most significant finding of this analysis is the emergence of Lesotho as a more assertive diplomatic actor despite domestic constraints. AU Peace and Security Council membership, active pursuit of AFCON co-hosting, and engagement in regional infrastructure initiatives signal ambition that transcends the kingdom’s small size and structural vulnerabilities. This diplomatic activism reflects recognition that multilateral engagement offers pathways to influence not available through bilateral channels alone.

For South Africa, Lesotho represents both strategic partner and stability concern. The water relationship ensures enduring South African interest in Lesotho’s functional governance and infrastructure development. However, Lesotho’s internal challenges—if unaddressed—could generate spillover effects requiring costly regional intervention. South African policy toward Lesotho must therefore balance respect for sovereignty with sustained engagement supporting stability and development.

For the broader Southern African region, Lesotho exemplifies both opportunities and challenges of small state integration. Its water resources demonstrate how regional infrastructure can generate mutual benefits. Its import dependency illustrates vulnerabilities that regional value chain development might address. Its political fragility highlights the importance of supporting governance institutions alongside infrastructure.

The relationship between Lesotho and its neighbors, in sum, reflects the complex interdependence that characterizes contemporary Southern Africa. Deep structural integration creates mutual dependencies that generate both resilience and vulnerability. Strategic resources provide leverage that partially offsets size asymmetries. Domestic governance performance fundamentally conditions external partnership opportunities. As Lesotho navigates these dynamics in the coming years, its trajectory will illuminate broader possibilities and constraints for small states in an increasingly integrated region.

References

-

In On Africa (IOA). (2026, January 8). Lesotho: Business Environment, Risks, and Market Opportunities. africa.com.

-

Lesotho News Agency. (2026, February 10). Lesotho Submits Candidature for AU Peace, Security Council. LENA.

-

Times of Eswatini. (2026, February 8). Lesotho joins AFCON bid, Eswatini mum. Times of Eswatini.

-

The Swaziland News. (2026, January 10). China zero tariffs for Africa, Eswatini excluded amid Taiwan ties. The Swaziland News.

-

TimesLIVE. (2026, February 11). SA joins AU’s security council for two-year term. TimesLIVE.

-

Assahifa. (2026, February 4). Africa’s Most Import-Dependent Economies Highlight Structural Trade Imbalances. Assahifa.

-

Lesotho Times. (2026, February 18). Youth blast Matekane over failure to curb unemployment. Lesotho Times.

-

Lesotho Times. (2026, February 4). Maqelepo speaks on 2028 AFCON bid. Lesotho Times.

-

HireBorderless. (2025, November 16). Employer of Record Services In Lesotho: 8 EOR Compared in 2026. Borderless AI.

-

APAnews. (2026, February 11). SADC approves $1.83m for Lesotho-Botswana Water Transfer Project. APAnews.