Abstract

This paper examines the contemporary economic and political status of Egypt within the North African regional context as of early 2026, drawing upon recent official data, international financial institution reports, and human rights documentation. The research identifies a fundamental paradox at the heart of Egypt’s regional positioning: the country is simultaneously experiencing a significant macroeconomic recovery—with GDP growth accelerating to 5.3%, inflation moderating, and portfolio inflows turning positive—while undergoing a profound political consolidation that has further concentrated power in the presidency, entrenched military-economic dominance, and systematically repressed all forms of dissent. This paper argues that Egypt’s regional influence is increasingly defined by this contradiction: international financial institutions and Western governments celebrate its economic stabilization and geostrategic reliability, even as the country’s political trajectory diverges sharply from the democratic governance models these same actors purport to promote. The analysis proceeds in three main sections: economic performance and structural transformation; domestic political consolidation and human rights; and regional foreign policy positioning, including Egypt’s complex relationship with the Maghreb. The conclusion assesses Egypt’s overall regional standing and the sustainability of its current trajectory.

Keywords: Egypt, North Africa, political economy, authoritarian consolidation, regional integration, IMF program

1. Introduction

Egypt occupies a distinctive and arguably preeminent position in the North African geopolitical landscape. As the Arab world’s most populous nation, the custodian of the Suez Canal—one of the world’s most strategic maritime chokepoints—and a state with deep historical resonance and substantial military capacity, Egypt’s trajectory carries weight far beyond its borders. The country’s regional role has been further elevated by the Gaza conflict, which has restored Cairo’s traditional position as an indispensable mediator in the Israeli-Palestinian arena.

This paper provides a deeply researched analysis of Egypt’s economic and political status as of early 2026, drawing upon official government data, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank assessments, investment bank analysis, diplomatic reporting from the World Economic Forum, and comprehensive human rights documentation. The timing is significant: the first months of 2026 have witnessed a major cabinet reshuffle emphasizing economic technocracy, the release of strong GDP growth figures, continued engagement with the IMF program, and a controversial constitutional referendum extending presidential rule—developments that collectively illuminate the contours of contemporary Egypt.

The analysis proceeds in three main sections. Section two examines Egypt’s economic performance and structural characteristics, analyzing the recent growth acceleration, sectoral dynamics, fiscal and external balances, and the evolving relationship with the IMF. Section three analyses the domestic political landscape, including the consolidation of presidential power, the February 2026 cabinet reshuffle, the intensification of repression against civil society and dissent, and the deteriorating human rights environment documented by international observers. Section four addresses Egypt’s foreign policy and regional role, examining its Gaza mediation, relations with North African neighbours, engagement with Gulf partners, and positioning vis-à-vis global powers. The conclusion synthesizes these findings to assess Egypt’s overall regional standing and the sustainability of its current trajectory.

2. Economic Status: Recovery, Reform, and Persistent Vulnerability

2.1 Growth Acceleration and Macroeconomic Stabilization

The Egyptian economy has demonstrated a notable acceleration in growth during the second quarter of fiscal year 2025/2026, marking what officials describe as the highest growth rate since the third quarter of FY2021/2022. According to Minister of Planning and Economic Development Ahmed Rostom, GDP expanded by 5.3% in Q2 FY2025/2026, with full-year growth now projected at 5.2%—a significant upward revision from the government’s initial target of 4.5% .

This growth acceleration reflects the cumulative impact of structural, fiscal, and monetary reforms implemented over recent years, which have strengthened macroeconomic stability and improved the economy’s resilience to domestic and external challenges . The recovery has been sufficiently robust to register in labour market indicators: the employment rate among women rose to 21.7% in Q2 FY2025/2026 from 18.5% in the same period a year earlier, while the overall unemployment rate fell to 6.2% .

International financial institutions have validated this positive trajectory. The IMF upgraded Egypt’s growth forecasts in late 2025, projecting 4.3% growth for 2025 and 4.5% for 2026 . The World Bank similarly revised its forecasts upward, adjusting the 2025/2026 FY projection to 4.3% (0.7 percentage points higher than previously estimated) and the 2026/2027 FY projection to 4.8% (0.2 points higher) . These revisions reflect a consensus that Egypt’s non-oil sectors are demonstrating sufficient momentum to offset ongoing headwinds, including reduced Suez Canal revenues and declining hydrocarbons extraction.

2.2 Sectoral Dynamics: The Drivers of Growth

The composition of Egypt’s growth reveals a economy undergoing significant structural transformation, with several labour-intensive sectors posting robust performance. Non-oil manufacturing grew by 9.6% in Q2 FY2025/2026, contributing 1.2 percentage points to the overall 5.3% growth rate . This performance reflects the government’s industrial localization strategy, stronger exports of finished and semi-finished goods, and efforts to position Egypt as a regional industrial hub .

Within manufacturing, specific subsectors have recorded remarkable growth rates: the automotive industry expanded by 126%, pharmaceuticals by 52%, and ready-made garments by 41% in the fourth quarter of FY2024/2025 . These figures suggest that targeted industrial policies and improved access to foreign currency for inputs are beginning to yield results.

The tourism sector has staged an impressive recovery, with restaurants and hotels growing by 14.6% in Q2 FY2025/2026 . Egypt received approximately 19 million visitors in 2025, a record figure that underscores the country’s enduring appeal as a tourist destination despite regional instability . By late 2025, tourist arrivals had already exceeded 17 million , indicating that the sector is on track to exceed pre-pandemic levels.

The Suez Canal, which suffered significant revenue losses due to Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea, has shown early signs of recovery. The canal recorded growth of 24.2% in Q2 FY2025/2026 as stability gradually returned to the region and the Suez Canal Authority implemented measures to encourage shipping traffic . However, this recovery remains partial, and canal revenues are unlikely to return to previous peaks in the near term.

The information and communications technology sector grew by 14.6% in Q4 FY2024/2025 , supported by government investment in digital infrastructure and 5G network deployment. Banking and insurance activities expanded by 10.73% and 12.85% respectively in Q2 FY2025/2026 , reflecting progress in financial inclusion and expanded access to financial services.

The oil and gas sector, by contrast, continues to experience contraction, though at a narrowing rate. The decline has been moderated by intensified drilling and exploration programs, as well as measures to facilitate operations for foreign partners and settle a significant portion of their financial dues during the current fiscal year . The government has committed to repaying between $250 million and $350 million in arrears to foreign oil companies in the first quarter of 2026 , a move designed to restore confidence and encourage renewed investment in exploration and production.

2.3 Fiscal and External Balances: Progress and Pressure

Egypt’s fiscal position has shown improvement, though significant challenges remain. Public debt declined from 98% of GDP in FY2022/2023 to 89% in FY2023/2024 . The government has articulated an ambitious target of reducing debt by $1-2 billion annually, aiming to reach a more sustainable trajectory by 2030 . This debt reduction effort is supported by the IMF program, which includes fiscal consolidation measures and structural reforms.

Inflation has moderated significantly from its peak. The IMF’s Research Department reported in late 2025 that inflation had fallen to its lowest level in 40 months, attributing the decline to monetary and fiscal policy tightening, resolution of foreign exchange shortages, and the fading impact of currency depreciation . However, consumer price inflation for typical goods and services still averaged 19.7% year-over-year in 2025 , indicating that the cost-of-living pressures facing ordinary Egyptians remain severe.

Portfolio flows have turned positive in recent months, with significant inflows into local currency bonds . This reversal reflects improved investor confidence following exchange rate unification, the clearance of import backlog, and progress on the IMF program. Goldman Sachs, following an investor trip to Egypt, described the currency as “well-supported in the short term,” aided by improved capital inflows and external debt issuance .

Despite these positive indicators, structural vulnerabilities persist. The investment bank’s analysis noted that some businesses are facing effective tax rates as high as 45%—double the 22.5% statutory rate—due to multiple demands for payment from as many as 67 different economic authorities . This tax burden, combined with regulatory opacity, continues to constrain private sector development.

The exchange rate remains a source of uncertainty. Market participants anticipate continued weakening of the Egyptian pound against the US dollar throughout 2025, with some projections forecasting an exchange rate of EGP 59/USD by year’s end . Such depreciation would exacerbate inflationary pressures and strain household purchasing power, even as it supports export competitiveness.

2.4 The IMF Program: Commitment and Calibration

Egypt’s economic reform program remains closely tied to its ongoing engagement with the International Monetary Fund. The current IMF program, which follows earlier arrangements dating to 2016, has provided policy anchors and financing assurances that facilitate access to other sources of external funding.

Goldman Sachs, following discussions with both Egyptian authorities and IMF officials, reported that “relations between the two remain good, with open and candid discussions taking place on an ongoing basis” . The bank perceived “a genuine commitment on the part of both parties to ensure the continued success of the program” .

Delays in the fourth review of the program have been attributed to efforts to recalibrate certain targets to better reflect “the evolution of the macro environment (particularly the external environment) and to ensure that the commitments under the program remain relevant and achievable” . This flexibility suggests a pragmatic approach from both sides, prioritizing program success over rigid adherence to initial targets.

President Sisi’s February 2026 directives to the new cabinet explicitly referenced the approaching conclusion of the IMF program at the end of the year, instructing the government to focus on reducing public debt “through new ideas that must be carefully studied to ensure the soundness of their procedures and their positive impact in both the short and long terms” . This guidance indicates that Egyptian authorities are already planning for the post-program period, seeking to lock in reform gains while preserving policy space.

2.5 Structural Reform and the Private Sector Agenda

A central theme of Egypt’s current economic strategy is the transition toward private sector-led growth. At the World Economic Forum’s Davos meeting in January 2026, President Sisi explicitly stated that “creating an attractive business environment for the private sector is a fundamental basis in the process of development and modernisation” . This message was reinforced by the February 2026 cabinet reshuffle, which brought in ministers with strong economic credentials, including a senior World Bank economist as planning minister .

The state ownership policy, which aims to reduce the public sector’s footprint in the economy and level the playing field for private enterprises, remains a stated priority. President Sisi’s February 2026 directives instructed the new government to proceed with “concrete steps” implementing this policy and “increasing the participation of the private sector in the economic sector” .

However, progress on structural reform has been slower than anticipated. Goldman Sachs noted that “conversations with local market participants revealed continued concern about the country’s macroeconomic outlook” and that “on the structural reform front, progress has been slower than expected, particularly when it comes to reducing the state’s role in the economy and creating a level playing field for private sector players” .

The military’s extensive economic role remains a particularly sensitive issue. The constitutional amendments approved in 2019 and the recent 2026 changes have further entrenched the military’s influence in political and economic life , creating inherent tensions with the private sector development agenda. As Human Rights Watch’s analysis noted, the constitutional changes “empower the executive and military at the expense of a weakened judiciary and legislature” , a configuration that complicates efforts to create genuinely competitive markets.

2.6 Social and Human Development Indicators

The macroeconomic recovery narrative coexists with troubling trends in social and human development indicators. Human Rights Watch’s analysis of the 2025/2026 state budget found that education spending amounted to just 1.5% of GDP (4.7% of government expenditure), “the lowest in over a decade” . Health care spending was similarly constrained at 1.2% of GDP (3.6% of government expenditure) . Both figures fall below constitutional requirements and international benchmarks, raising questions about the sustainability of human capital development.

Poverty rates remain elevated. Unpublished official data cited by independent media indicated that 34% of the population were experiencing multidimensional poverty in 2021-2022, “the highest nationally defined poverty rate found by the government’s Income, Expenditure, and Consumption Survey since its inception in 1999” . This poverty level, combined with persistent inflation, has undermined the right to food and an adequate standard of living for millions of Egyptians.

The government’s continued prioritization of large infrastructure projects despite recurring economic crises has drawn criticism from rights organizations . While these projects—including new administrative capitals, road networks, and energy infrastructure—have contributed to growth and employment, they have also absorbed substantial public resources that might otherwise have been directed to health, education, and social protection.

3. Political Status: Authoritarian Consolidation and the Deepening Sisi System

3.1 The February 2026 Constitutional Amendments

The most significant political development of early 2026 was the overwhelming approval of constitutional amendments that could extend President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s rule until 2030. According to the National Election Authority, 88.83% of voters approved the changes in a three-day referendum, with turnout officially recorded at 44.33% .

The amendments represent the latest phase in a process of authoritarian consolidation that has accelerated since Sisi’s military overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013. Sisi’s current term was initially set to end in 2022 but was retroactively extended by two years under previous constitutional changes . The 2026 amendments create the near-certainty that Sisi will run for another six-year term in the next presidential election.

Beyond presidential term extension, the constitutional package includes provisions strengthening Sisi’s control over the judiciary and giving the military even greater influence in Egyptian political life . These changes further erode the separation of powers and institutionalize the military’s privileged position within the political system.

The referendum process drew sharp criticism from rights organizations. Human Rights Watch’s deputy director for the Middle East and North Africa characterized the amendments as “a shameless attempt to entrench the military’s power over civilian rule” and stated that the referendum “took place in such an unfree and unfair environment that its results can have no pretence to legitimacy” . The rushed nature of the process—parliament approved the amendments just days before the vote, giving voters minimal time to digest changes to 20 constitutional articles—was widely noted .

Egyptian analysts expressed concern about the long-term implications. Mai El-Sadany, legal director at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, warned that the amendments “eat away at the separation of powers, deteriorates the rule of law, and silences spaces for independent dissent” . Veteran political scientist Hassan Nafaa questioned how “a constitution can be changed to tailor-fit one person,” warning that the changes set a dangerous precedent for future rulers beyond Sisi’s tenure .

3.2 The February 2026 Cabinet Reshuffle

The constitutional referendum was followed by a significant cabinet reshuffle approved by parliament on February 10, 2026. The reshuffle brought 13 new ministers into the government, with a clear emphasis on economic expertise and technocratic competence .

Key appointments included Ahmed Rostom, a senior World Bank economist, as minister of planning; Mohamed Farid Saleh, chairperson of the Financial Regulatory Authority, as minister of investment; and the retention of Rania Al-Mashat in a reorganized planning and international cooperation portfolio . The reshuffle also created the position of deputy prime minister in charge of economic affairs, signaling an intention to improve policy coordination across economic ministries .

Two women were included in the new line-up: Randa al-Menshawi as housing minister and Gihane Zaki as culture minister . The State Ministry of Information was restored after being dissolved in 2021, with Diaa Rashwan, chairman of the State Information Service, appointed as minister .

The reshuffle left key portfolios of foreign affairs and defence unchanged, reflecting continuity in Egypt’s core national security apparatus . The emphasis on economic management in the reshuffle suggests that the government recognizes the centrality of economic performance to regime stability, while the unchanged security leadership indicates that the military-security establishment remains the ultimate guarantor of the political order.

President Sisi’s directives to the new cabinet, issued on February 10, established a comprehensive framework for government action. The directives focused on economic reform, social development, and national security, reaffirming the pillars established in the original decree appointing Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly . Each ministry was instructed to develop a detailed plan “that includes targets, procedures, implementation timelines, necessary funding, and key performance indicators,” subject to “continuous monitoring and evaluation” .

3.3 The Repression of Civil Society and Dissent

The February 2026 political developments occurred against a backdrop of sustained and intensifying repression against all forms of dissent. Human Rights Watch’s World Report 2026, covering events of 2025, documented a political environment in which Egyptians “continued to live under the authoritarian grip of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s government,” with authorities “cracking down on peaceful critics and systematically repressing human rights defenders” .

Civic space has become severely curtailed under Egypt’s 2019 associations law, which imposes draconian restrictions on independent organizations. The Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, one of the few remaining independent human rights groups inside Egypt, reported that apparent security harassment prevented them from opening a bank account for 11 months even after registering under the law . Human rights defenders faced continued judicial and security harassment, with leading figures subjected to interrogation, travel bans, and asset freezes .

The justice system has been weaponized against critics. Authorities continued the practice, denounced by the UN human rights chief, of “recycling” detainees—bringing new cases against them almost identical to previous ones to keep critics in detention . Remote hearings via video conference for pretrial detention renewal became routine, preventing judges from assessing the legality and conditions of detention and violating fair trial guarantees .

Mass trials proceeded on an enormous scale. In May 2025, trials began for some 6,000 people referred to criminal courts in “terrorism” cases, with more than half having been in pretrial detention for months or years . These proceedings routinely fail to provide fair trial guarantees, with defendants held indefinitely without material evidence of wrongdoing or establishment of individual criminal responsibility .

Conditions in detention facilities amount to ill-treatment and torture. Prisoners face denial of health care, prolonged solitary confinement, and deteriorating conditions that have prompted suicide attempts. By September 2025, 44 detainees had died in custody according to the Committee for Justice . Cases of deliberate withholding of medical care from prominent detainees, including Egyptian-American academic Dr. Salah Soltan and lawyer Houda Abdel Moneim, have been well-documented .

3.4 Freedom of Expression and Media

Freedom of expression has been effectively extinguished in Egypt. Peaceful protests and gatherings remained effectively banned under draconian laws, with authorities punishing dissenting expression across all media platforms .

Journalists at independent outlets faced persistent security and judicial harassment. Egypt continued to rank among the worst 10 countries globally in the number of detained journalists according to the Committee to Protect Journalists . As of May 2025, 23 journalists were in jail according to the head of the Journalists’ Syndicate, most in prolonged pretrial detention . Independent journalist Ismail Iskandarani was detained in September 2025 over Facebook posts, facing state security charges alongside a peaceful Sinai activist .

The case of Egyptian-British activist Alaa Abdel Fattah illustrated the regime’s determination to punish dissent even when legal sentences have been served. Pardoned by President Sisi in September 2025 after almost continuous detention since 2014, Abdel Fattah was prevented from leaving the country at Cairo International Airport in November . This pattern—granting clemency while maintaining control—exemplifies the regime’s calibrated approach to dissent management.

Economics expert Abdel Khaleq Farouk, detained since October 2024, was sentenced in October 2025 to five years in prison over criticism of the government’s economic policies . This prosecution of a professional for policy commentary sent a chilling signal to anyone considering public critique of economic management.

A renewed wave of arrests targeted online content creators in mid-2025, with at least 29 individuals—mostly women—prosecuted on vague charges including violating “public morals,” “undermining family values,” and “money laundering” based on “indecent” videos posted to social media . Human Rights Watch documented 21 more such prosecutions in October , indicating that this crackdown on digital expression was intensifying.

3.5 Parliamentary Elections and Political Opposition

Egypt’s parliamentary elections, held in August and November 2025, exemplified the absence of genuine political competition under current conditions. The elections authority eliminated all party lists except one dominated by pro-Sisi parties and disqualified almost 200 candidates for individual seats, including some on grounds as trivial as exclusion from military service decades ago . Rights organizations criticized the elections for lacking genuine competition and for reported violations, noting they were conducted “under a general state of repression” .

The formal opposition landscape has been hollowed out. Islamist opposition, decimated by the post-2013 crackdown that killed hundreds and imprisoned tens of thousands, poses no organized challenge. Secular and liberal critics have been silenced through a combination of co-optation, repression, and exile. The Muslim Brotherhood, designated a terrorist organization, operates only in diaspora, with any suspected links to the group sufficient grounds for prosecution and imprisonment.

3.6 Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Rights

Egypt’s performance on gender equality remains poor by international standards. In the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2025, Egypt ranked 139th out of 148 countries, placing it among the ten worst globally for gender parity . Despite some government efforts on political participation and improved access to health care, women continue to face systematic barriers including gender-based violence, pay-gap inequality, and discriminatory personal status laws .

Authorities continued to use vague penal code provisions, such as those criminalizing “debauchery,” to target and imprison LGBT individuals for consensual same-sex conduct . This persecution reflects the regime’s alignment with socially conservative currents and its willingness to use moral panics to demonstrate cultural authenticity while distracting from political and economic failures.

3.7 Refugees and Migration

Egypt’s refugee and migrant population has grown dramatically, driven primarily by the ongoing conflict in Sudan. As of August 2025, Egypt hosted over 1 million refugees and asylum seekers registered with UNHCR, including more than 770,000 who had fled Sudan since April 2023 . Many additional Sudanese remain unregistered.

The government’s response to this influx has drawn criticism. Rights groups reported deportations of refugees and asylum seekers, including Sudanese nationals, in violation of the principle of nonrefoulement . Poor living conditions for migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees, combined with barriers to education—tens of thousands of refugee children remain out of school—have created a humanitarian situation that strains both host communities and displaced populations .

4. Regional Position: Mediation, Competition, and Strategic Alignment

4.1 The Gaza Conflict and Egypt’s Mediation Role

The Gaza conflict has restored Egypt to a central position in regional diplomacy, leveraging its geographical contiguity with Gaza, its historical role as a mediator between Israelis and Palestinians, and its working relationships with all relevant parties. At the World Economic Forum’s Davos meeting in January 2026, Egyptian Finance Minister Ahmed Kouchouk articulated Cairo’s perspective: “Gaza and Palestine is the core problem for the region, and if it is solved it will pay dividends for the entire region, not only for close neighbours like Egypt” .

Egypt’s mediation efforts have focused on securing ceasefires, facilitating hostage and prisoner exchanges, and coordinating humanitarian access. The country’s relative stability and its functional, if cool, diplomatic relations with Israel make it an indispensable interlocutor. The humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza has also generated international engagement that flows through Cairo, enhancing Egypt’s diplomatic visibility.

However, the Gaza conflict has imposed significant economic costs on Egypt. The Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping, launched in solidarity with Palestinians, sharply reduced Suez Canal revenues—a major source of foreign currency. The partial recovery noted in Q2 FY2025/2026 suggests that some shipping is returning, but the canal’s revenue stream remains diminished and uncertain.

The conflict has also complicated Egypt’s relations with various actors. Cairo’s cautious approach to the Gaza crisis—maintaining relations with Israel while supporting Palestinian relief efforts—reflects its traditional balancing act but has drawn criticism from some quarters. The presence of large numbers of Sudanese refugees fleeing a separate conflict adds another layer of complexity to Egypt’s regional humanitarian engagement.

4.2 Relations with North African Neighbours

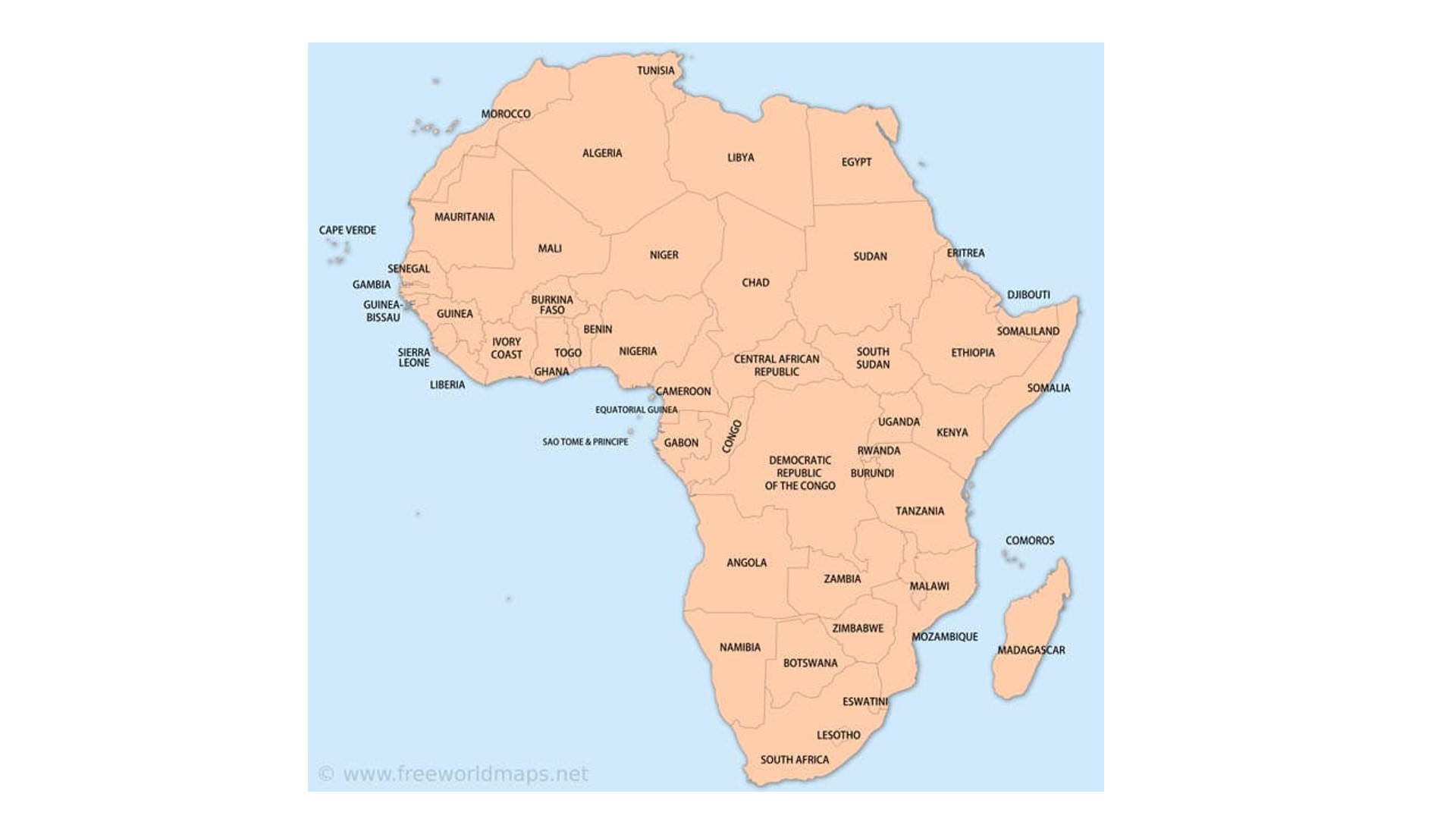

Egypt’s relationships with its North African neighbours present a mixed picture, characterized by limited economic integration, diplomatic distance from Maghreb institutions, and bilateral ties that vary significantly by country.

The most notable feature of Egypt’s Maghreb policy is its long-standing but unfulfilled aspiration to join the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA). As a detailed retrospective analysis notes, Egypt formally applied to join the UMA in 1994, a move that sparked debate about whether it signaled a strategic pivot away from its traditional Eastern orientation . Then-Foreign Minister Amr Moussa emphasized at the time that Egypt “could not withdraw from the East under any circumstances” and that the request to join was “not a shift but an addition,” reflecting the understanding that “everyone [is] part of a single geographical area” .

The UMA, however, has been paralyzed by the fundamental disagreement between its two largest members, Morocco and Algeria, over Western Sahara. King Hassan II of Morocco initially welcomed Egypt’s interest, instructing his foreign minister to communicate that Morocco would work to make Egypt “a full member of the Maghreb Union, not just an observer” . However, the King’s death and the subsequent intensification of the Morocco-Algeria rivalry left the UMA in a state of “clinical death” , with Egypt’s membership aspiration unrealized.

The analyst suggests that “hope remains to breathe life back into this aborted union, with the prospect of finding a solution to the Western Sahara dispute within the framework of Moroccan sovereignty” . Recent diplomatic developments—including France’s alignment with Morocco on Western Sahara and UN Security Council resolutions favouring Morocco’s autonomy proposal—may create conditions for renewed regional integration efforts. However, the Libyan crisis “could once again push the region into a grey zone, if not a dark one” , complicating any regional architecture.

Bilaterally, Egypt maintains functional relationships with all Maghreb states, though their intensity varies. Relations with Libya are complicated by the country’s fragmentation and the presence of multiple competing authorities. Egypt has historically supported the Libyan National Army under Khalifa Haftar, viewing it as a bulwark against Islamist and extremist groups, while also engaging with the internationally recognized government in Tripoli. The ongoing Libyan crisis generates security spillovers, including weapons smuggling and potential terrorist threats, that preoccupy Egyptian security planners.

Relations with Tunisia have been generally cordial but limited in depth, constrained by Tunisia’s smaller economic weight and its preoccupation with domestic political and economic challenges. The authoritarian turn under President Kais Saied, while sharing some characteristics with Egypt’s political model, has not generated particularly close bilateral coordination.

Relations with Algeria are correct but not warm, reflecting Algeria’s traditional rivalry with Morocco (with which Egypt maintains closer ties), differing approaches to regional conflicts, and competition for influence in Libya. Algeria’s support for the Polisario Front in Western Sahara places it on the opposite side of that dispute from Morocco and its international backers, including the United States and France. Egypt has generally avoided taking positions that would alienate either party, maintaining a studied neutrality that limits its ability to mediate.

4.3 The Gulf Relationship: Financial Support and Strategic Alignment

Egypt’s relationship with the Gulf Arab states—particularly Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait—constitutes a cornerstone of its regional positioning. This relationship has provided critical financial support during periods of economic stress, including following the 2013 military takeover and during the subsequent stabilization programs.

The Gulf states have viewed Egypt’s stability and its alignment against political Islam as essential to their own security. Following the overthrow of President Morsi, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait provided billions of dollars in grants, deposits, and in-kind support that helped stabilize Egypt’s finances and signal international confidence. This support has continued, though with greater conditionality and at reduced levels, through subsequent years.

The relationship extends beyond finance to encompass security cooperation, political coordination, and economic integration. Egyptian labour migration to the Gulf provides remittances that support the balance of payments and household incomes. Gulf investment in Egyptian real estate, infrastructure, and energy projects has grown, though it remains below potential due to regulatory and bureaucratic impediments.

The Gulf states’ own economic transformation agendas—particularly Saudi Vision 2030 and UAE economic diversification—create both opportunities and challenges for Egypt. Opportunities arise from increased Gulf demand for goods, services, and investment destinations. Challenges stem from competition for investment and the need to ensure that Egyptian interests are protected in Gulf-driven regional initiatives.

4.4 Relations with Turkey: The Reconciliation Process

Egypt’s relationship with Turkey has undergone significant evolution, moving from acute hostility following the 2013 military overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood-aligned Morsi government toward a managed reconciliation. Turkey had been the most vocal international critic of the 2013 events and a haven for exiled Egyptian Islamists, generating deep bilateral tensions.

The reconciliation process, initiated in 2021 and gradually deepened since, reflects mutual recognition that sustained hostility served neither country’s interests. For Egypt, improved relations with Turkey reduce regional friction and open economic opportunities. For Turkey, rapprochement with Egypt facilitates access to Libyan political processes, expands export markets, and reduces diplomatic isolation.

The relationship remains pragmatic rather than warm, with continuing differences over Libya, maritime boundaries in the Eastern Mediterranean, and the treatment of Muslim Brotherhood affiliates. However, the restoration of ambassadorial-level diplomatic relations and expanding trade and investment ties indicate that both sides see value in managed engagement.

4.5 Relations with Israel: Calculated Cooperation

Egypt’s relationship with Israel, governed by the 1979 peace treaty, remains cold but functional—a “cold peace” that has survived regional upheavals and periodic crises. The treaty provides the framework for security coordination, particularly in Sinai, where both countries face threats from extremist groups. Egyptian mediation in Gaza necessarily involves communication with Israeli authorities, and security cooperation on counterterrorism continues largely out of public view.

The Gaza war has tested this relationship, generating public anger in Egypt toward Israel while requiring continued official coordination. Egypt has sought to balance its treaty obligations and its mediation role with responsiveness to public sentiment, maintaining the peace while criticizing Israeli actions and supporting Palestinian relief.

The long-term trajectory of Egyptian-Israeli relations depends on multiple factors, including the resolution of the Palestinian issue, the evolution of regional alignments, and domestic political dynamics in both countries. For now, the peace treaty remains a cornerstone of Egypt’s regional posture, providing stability on its eastern flank and facilitating continued US security assistance.

4.6 Great Power Relations: Balancing and Leverage

Egypt’s relations with global powers reflect a strategy of diversification and leverage maximization. The United States remains the most important external partner, providing annual military assistance of approximately $1.3 billion as a legacy of the peace treaty with Israel. This assistance, while reduced from historical levels and subject to occasional congressional conditionality, sustains Egypt’s US-equipped military and signals the strategic relationship.

However, Egypt has actively diversified its great power relationships to reduce dependence and increase policy space. Russia has become an important arms supplier, with significant weapons purchases including advanced aircraft and air defence systems. These purchases serve both military requirements and political purposes, signalling Egypt’s ability to turn to alternative suppliers if US cooperation becomes too conditional.

China has emerged as a significant economic partner, with investments in infrastructure, energy, and industrial projects under the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese financing and construction have supported major projects including the new administrative capital. Trade between the two countries has expanded significantly, with China becoming a major source of imports and, increasingly, a market for Egyptian exports.

The relationship with the European Union is multifaceted, encompassing trade (the EU is Egypt’s largest trading partner), energy cooperation (including natural gas and potential hydrogen), migration management, and political dialogue. EU financial support, including macro-financial assistance and investment programs, complements IMF and Gulf financing.

Egypt’s positioning among great powers is facilitated by its geostrategic location, its role in regional conflicts, and its relative stability in a turbulent neighbourhood. These assets enable Cairo to attract support from multiple quarters while resisting pressure from any single partner. However, this balancing strategy requires careful management to avoid triggering negative reactions from any major power and to ensure that diversified relationships remain mutually compatible.

5. Conclusion: Egypt’s Regional Standing and Future Trajectory

Egypt in early 2026 presents a profound paradox: an economy demonstrating genuine recovery and stabilization, with accelerating growth, moderating inflation, returning portfolio inflows, and a reform program endorsed by international financial institutions; coexisting with a political system undergoing further authoritarian consolidation, with extended presidential tenure, entrenched military power, systematic repression of dissent, and deteriorating human rights indicators.

This paradox defines Egypt’s regional standing and shapes its future trajectory. Internationally, Egypt is treated as an indispensable partner—a mediator in Gaza, a counterterrorism collaborator, a manager of migration flows, and a relatively stable anchor in a volatile region. The macroeconomic recovery validates the reform program and attracts continued support from the IMF, World Bank, and bilateral partners. Western governments, in particular, have demonstrated willingness to compartmentalize human rights concerns, maintaining security and economic cooperation while issuing mild criticisms of political repression.

Regionally, Egypt’s influence is significant but constrained. The Gaza crisis has restored Cairo to a central diplomatic role, leveraging its unique position as neighbour to both Israel and Gaza. Relations with Gulf states provide financial support and strategic alignment. Ties with sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Nile Basin countries, remain complicated by the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam dispute, which continues to fester without resolution. Relations with Maghreb neighbours are correct but limited, with Egypt’s long-standing aspiration to join the Arab Maghreb Union remaining unrealized due to the Morocco-Algeria rift and the UMA’s paralysis.

Domestically, the sustainability of Egypt’s current trajectory faces three critical tests. The first is economic: whether growth can be sustained and translated into improved living standards for ordinary Egyptians. Despite positive macroeconomic indicators, poverty remains high, public services are underfunded, and inflation continues to strain household budgets. The fiscal consolidation required by the IMF program will require difficult trade-offs between debt reduction and social spending.

The second test is political: whether the intensified repression of recent years can indefinitely contain dissent. The regime has demonstrated effectiveness in silencing organized opposition and deterring protest, but underlying grievances—economic hardship, lack of political voice, injustice—remain unaddressed. The Hirak movement in Algeria and the Sudan uprising demonstrated that apparently stable authoritarian systems can be shaken when conditions align. Egypt’s security apparatus remains formidable, but no repressive system is invulnerable.

The third test is structural: whether the promised transition to private sector-led growth can occur while the military’s economic empire remains intact and political power remains concentrated. The state ownership policy and private sector development agenda face inherent contradictions with a system that privileges military-owned enterprises, politically connected firms, and state-dominated economic governance. Resolving these contradictions will require political choices that the current configuration of power makes difficult.

Looking forward, Egypt’s trajectory will be shaped by several key variables: the evolution of regional conflicts, particularly Gaza and Libya; the continued availability of external financing from Gulf partners and international institutions; the regime’s capacity to manage economic adjustment without triggering unrest; and the durability of the political settlement consolidated under Sisi. The country’s substantial assets—demographic weight, geostrategic location, institutional capacity, historical legitimacy—provide foundations for a positive trajectory. Whether these assets can be translated into sustainable development and genuine regional leadership depends on political choices that remain to be made—and on whether the paradox at the heart of Egypt’s current configuration can be resolved.

References

-

ZAWYA. (2026, February 18). “Egypt’s GDP growth accelerates to 5.3% in Q2 FY2025/26: Rostom.” https://www.zawya.com/en/economy/north-africa/egypts-gdp-growth-accelerates-to-53-in-q2-fy2025-26-rostom-un8o4rjh

-

State Information Service, Egypt. (2026, February 10). “El-Sisi issues directives for new cabinet; economic reform, innovation, national security.” https://sis.gov.eg/en/media-center/news/el-sisi-issues-directives-for-new-cabinet-economic-reform-innovation-national-security/

-

World Economic Forum. (2026, January 27). “The Middle East and North Africa at Davos 2026.” https://www.weforum.org/stories/2026/01/mena-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-davos-2026/

-

okazinvest.com. (2026, February 15). “Egypt sees positive portfolio inflows amid debt, inflation challenges: IMF.” http://okazinvest.com/okaz/newDetails.aspx?id=978133&nb=2

-

New Age BD. (2026, February 17). “Egyptians approve changes extending Sisi’s rule.” https://www.newagebd.net/article/70721/

-

Al Jazeera. (2026, February 10). “Egypt’s parliament backs economy-focused cabinet reshuffle.” https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/2/10/egypts-parliament-backs-economy-focused-cabinet-reshuffle

-

Annahar. (2026, February 19). “Egypt and the Maghreb dream: A journey toward regional unity.” https://www.annahar.com/en/opinion/278909/egypt-and-the-maghreb-dream-a-journey-toward-regional-unity

-

World Journal. (2025, October 26). “世銀看好…埃及製造業、旅遊、資通訊高飛 拚1年減債20億.” https://www.worldjournal.com/wj/story/121261/9088532

-

Human Rights Watch / ecoi.net. (2026). “World Report 2026: Egypt.” https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2136208.html

-

okazinvest.com. (2026, February 15). “Goldman Sachs cautiously optimistic for Egypt’s economy in latest note.” http://www.okazinvest.com/okaz/newDetails.aspx?id=1022455&nb=2