Abstract

This paper examines Zambia’s contemporary economic and political status, with particular attention to its relationship with the East African Community, revealing a nation navigating a fundamental tension between its Southern African historical orientation and its growing strategic engagement with East Africa. Economically, Zambia is experiencing a robust recovery, with GDP growth projected to reach 5.8 percent in 2026, driven by mining expansion, agricultural recovery, and infrastructure investment. The completion of a 38-month IMF Extended Credit Facility program and successful debt restructuring negotiations mark significant milestones in restoring macroeconomic stability, with public debt projected to decline from 133 percent of GDP in 2023 to 80 percent by 2026. However, structural vulnerabilities persist: extreme dependence on copper exports, vulnerability to climate-induced power shortages, and poverty affecting 62 percent of the population. Politically, Zambia faces a critical democratic test as the August 2026 elections approach amid contentious constitutional amendments and concerns about democratic backsliding. President Hichilema’s push for pre-election constitutional changes has sparked fierce debate between proponents citing electoral integrity and critics warning of self-interested power consolidation. Regionally, Zambia occupies a unique intersection: a SADC and COMESA member whose infrastructure ambitions increasingly connect it to East African trade routes through the Lobito Corridor, TAZARA railway rehabilitation, and energy integration with Tanzania. This paper argues that Zambia’s status embodies the paradox of a state achieving hard-won economic stabilization while confronting democratic legitimacy challenges, and whose geographic position enables strategic diversification between eastern and southern African integration pathways—with profound implications for its relationship with the East African Community.

1. Introduction

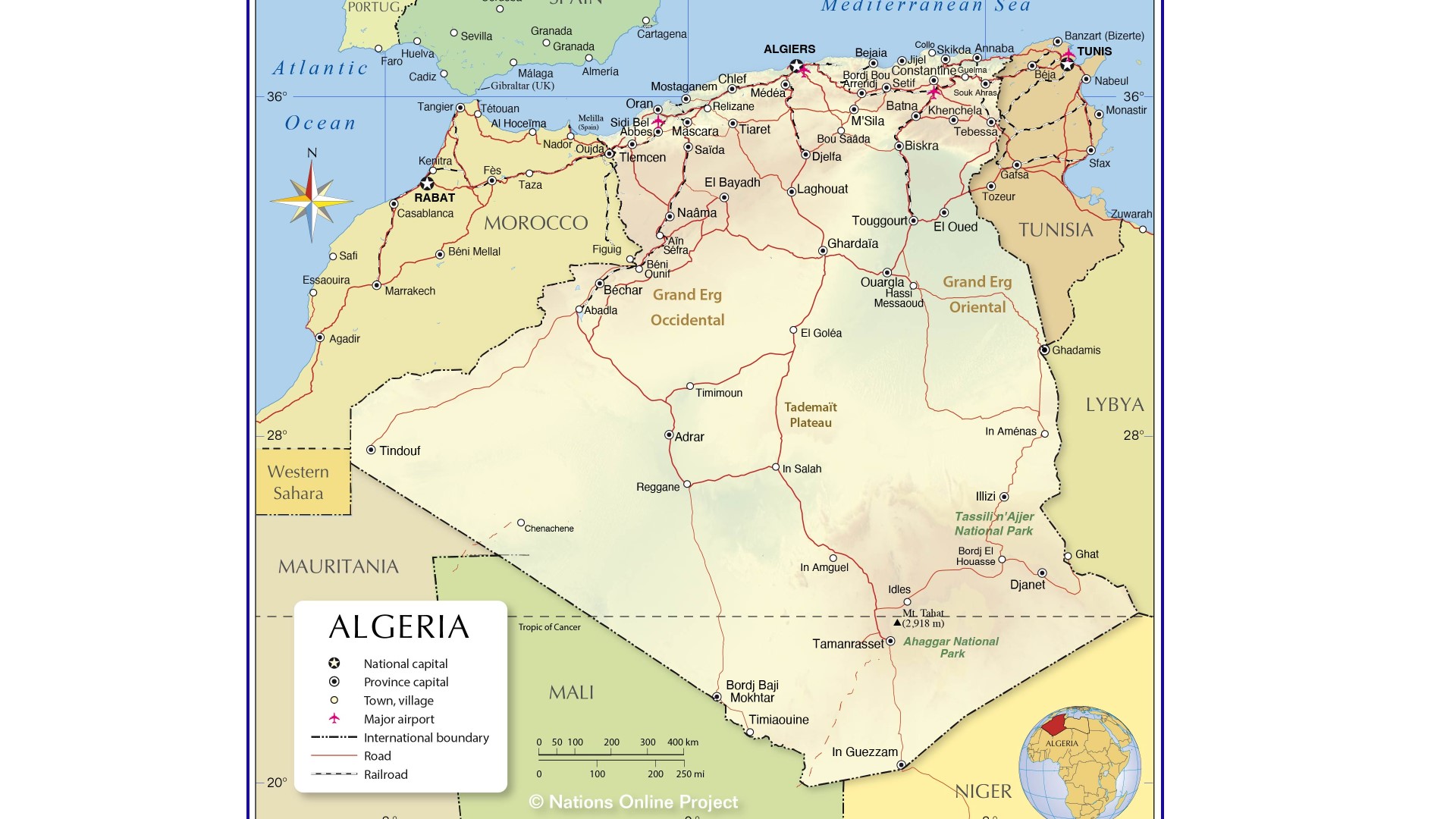

Zambia occupies an unusual and strategically significant position at the intersection of Eastern and Southern Africa. As a landlocked nation bordered by eight neighbors—including the Democratic Republic of Congo to the north, Tanzania to the northeast, and the SADC heartland to the south and west—it sits astride multiple regional formations. It is a founding member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), yet its infrastructure ambitions increasingly point eastward, toward Tanzanian ports and the Indian Ocean trade routes that connect to global markets.

This geographic position creates both opportunity and complexity. For the East African Community, Zambia represents a potential corridor partner and a gateway to the Southern African market. For Zambia, engagement with East Africa offers diversification away from dependence on southern routes and access to new trade and investment partners. Yet Zambia is not an EAC member state—its primary institutional homes remain SADC and COMESA—raising questions about the nature and depth of its relationship with the East African bloc.

In early 2026, Zambia presents a study in hard-won economic recovery juxtaposed with democratic uncertainty. Economically, the country has emerged from the shadows of its 2020 sovereign default—the first African pandemic-era default—to achieve macroeconomic stabilization. The IMF forecasts real GDP growth at 5.8 percent in 2026, up from an estimated 5.2 percent in 2025, driven by electricity production recovery, strong mining and services activity, and improved investor confidence . The successful completion of a 38-month Extended Credit Facility program, with total disbursements of $1.7 billion, marks a significant milestone in restoring credibility with international partners . Public debt is projected to decline from 133 percent of GDP in 2023 to 90.7 percent in 2025 and approximately 80 percent by 2026 .

Politically, however, the landscape is more contested. President Hakainde Hichilema’s push to amend the Constitution before the August 2026 general elections has ignited fierce debate. Government spokespersons frame the changes as necessary to address “lacunae” that could disrupt the electoral process and ensure “a predictable and stable constitutional framework” . Critics, including civil society organizations and opposition figures, warn that rapid, opaque amendments risk “weakening fairness and public confidence in governance systems” and undermining Zambia’s long history of peaceful democratic transitions .

Regionally, Zambia is pursuing an ambitious infrastructure agenda that increasingly connects it to East Africa. The Lobito Corridor development—a tripartite initiative with Angola and the DRC—will provide access to the Atlantic through the port of Lobito . Simultaneously, the rehabilitation of the TAZARA railway and grid interconnection with Tanzania position Zambia to utilize the port of Dar es Salaam more effectively . These infrastructure investments, combined with energy cooperation through the Southern African Power Pool and bilateral projects like the Batoka Gorge dam, create deepening interdependence with East African partners .

This paper investigates Zambia’s multifaceted status through four analytical lenses. Section two examines economic recovery, debt restructuring, and structural vulnerabilities. Section three analyzes political dynamics, including constitutional amendments, electoral preparations, and democratic governance concerns. Section four considers Zambia’s regional positioning—its relationship with the EAC, infrastructure corridors, and energy integration. Section five addresses the tensions between eastern and southern orientations and their implications for Zambia’s future trajectory.

2. The Economic Dimension: Recovery, Restructuring, and Resilience

2.1 Growth Trajectory and IMF Engagement

Zambia’s economic performance in 2025-2026 reflects a sustained recovery from the dual shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and sovereign default. According to the International Monetary Fund, real GDP growth reached an estimated 5.2 percent in 2025 and is projected to accelerate to 5.8 percent in 2026 . Coface, the credit insurance group, offers an even more optimistic forecast of 6.4 percent growth for 2026 .

This growth trajectory is driven by multiple factors. Electricity production recovery following improved hydrological conditions has restored industrial activity and household consumption. Strong mining sector performance, supported by elevated copper prices and new investment, has boosted exports and government revenues. Services activity, particularly in finance, transport, and tourism, continues to expand. The IMF notes that “the medium-term outlook remains favorable and depends on increased mining investment, robust agricultural production, improved electricity generation, and sustained fiscal discipline” .

The completion of the 38-month Extended Credit Facility (ECF) program in January 2026 represents a significant milestone. The IMF approved a final disbursement of $190 million, bringing total financing under the program to $1.7 billion since August 2022 . The Fund assessed that “program performance has been broadly satisfactory, despite some delays in the implementation of structural benchmarks,” with all quantitative performance criteria for end-June 2025 met except for net international reserves targets .

2.2 Inflation Dynamics and Monetary Policy

Inflation has moderated from crisis peaks but remains elevated. After averaging 15 percent in 2024, inflation declined to approximately 14 percent in 2025 and is projected to fall further to 9 percent in 2026 . The IMF expects inflation to “slow and gradually converge toward the 6 to 8 percent target range by 2027” .

This disinflation reflects multiple factors: lower global commodity prices, a restrictive monetary policy stance, appreciation of the kwacha against the dollar as investor confidence improves, and net foreign currency inflows from FDI, export earnings, and IMF disbursements . The easing of pressure on imported goods prices—particularly fuel and food—has provided relief to households and businesses.

2.3 Debt Restructuring and Fiscal Sustainability

Zambia’s debt restructuring journey offers lessons for other crisis-affected economies. After accumulating debt rapidly in the 2010s through Eurobond issuances (totaling $3 billion) and bilateral loans primarily from China, public debt reached approximately $35 billion (nearly $30 billion external) by 2020 . Unable to service debt representing more than 50 percent of public revenue, Zambia became the first African country to default during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The restructuring process, conducted through the G20 Common Framework, has achieved significant progress. Agreements with official bilateral creditors include rescheduling over more than 20 years, interest rates reduced to 1-2.5 percent, and a three-year grace period. An agreement with Eurobond holders was reached in 2024 . As a result, public debt is projected to decline dramatically: from 133.4 percent of GDP in 2023 to 124 percent in 2024, 92 percent in 2025, and approximately 80 percent in 2026 .

However, the IMF cautions that “public debt remains sustainable but exposed to a high risk of overall and external debt distress” . At the end of September 2025, two-thirds of the country’s debt was held by foreign creditors and denominated in foreign currency: 17 percent multilateral, 22 percent bilateral (China, Paris Club, Saudi Arabia, India), and 20 percent private . Negotiations continue with Afreximbank and the Trade and Development Bank (TDB), whose preferred creditor status Zambia contests given the commercial terms of their loans .

The fiscal position shows improvement. Despite a primary surplus, the overall public deficit widened in 2025 due to exceptional expenditure on arrears clearance and interest payments. For 2026, the deficit is expected to narrow to approximately 2 percent of GDP, supported by increased mining revenues, partial removal of import duty exemptions, and expanded excise duties .

2.4 External Sector Transformation

Zambia’s external position has strengthened considerably. The current account, which registered deficits of 3 percent of GDP in 2023 and 2.6 percent in 2024, returned to surplus of 1.5 percent in 2025 and is projected to reach 2.5 percent in 2026 . This improvement reflects robust export growth, particularly copper, which accounts for approximately 40 percent of export revenues.

Export composition reveals both concentration and emerging diversification. Copper dominates, with Switzerland (41 percent of exports) and China (18 percent) as primary destinations—Switzerland serving as a trading hub for commodity traders rather than final consumption . The Democratic Republic of Congo accounts for 15 percent of exports, reflecting integrated value chains in the copper belt region. Imports are dominated by South Africa (26 percent), China (17 percent), and the UAE (8 percent) .

Foreign direct investment continues to flow, particularly into mining (from Canada, Australia, the UK, China, and the US), energy, and infrastructure. These inflows, combined with the current account surplus, are building foreign exchange reserves toward the target of four months of import cover .

2.5 Structural Vulnerabilities: Copper Dependence and Climate Risk

Despite recovery, structural vulnerabilities persist. Extreme dependence on copper leaves the economy exposed to price volatility and demand fluctuations in key markets, particularly China. While new mines are opening and existing ones expanding—supported by FDI—diversification into other minerals (cobalt, nickel, manganese) and sectors remains limited.

Climate vulnerability represents an existential threat. Hydroelectricity accounts for approximately 85 percent of power generation, making the economy acutely sensitive to drought conditions. The 2024 drought severely affected hydropower production, triggering power cuts that disrupted industrial activity and household consumption . In response, the government is diversifying the energy mix through solar and other renewable investments . The Zambezi River Authority’s recent decision to increase annual water allocation for power generation to 30 billion cubic metres for 2026 provides some relief .

Poverty and inequality remain deeply entrenched. The World Bank projects poverty will decline by about one percentage point annually through 2027—progress too slow to substantially improve living conditions for the 62 percent of the population classified as poor . As Coface notes, growth has “failed to substantially reduce unemployment and poverty or improve the living conditions of the most vulnerable people in the country” .

2.6 Investment Climate and Private Sector Development

The Hichilema administration’s pro-market orientation has improved the business climate. Economic liberalization, commitment to debt restructuring, and re-engagement with Western partners have attracted investor interest. Massive investments are underway in economic zones and industrial parks focused on construction materials, steel, agri-food products, electrical components, batteries, and textiles .

Infrastructure investment is accelerating through public-private partnerships. Road projects connecting major cities are expected to be completed in 2027. Rail corridors—both the Lobito Corridor to the Atlantic and the TAZARA rehabilitation to Dar es Salaam—will reduce transport costs and improve export competitiveness .

However, constraints remain. The credit system remains underdeveloped, limiting access to finance for small and medium enterprises. Workforce training lags behind investor needs. Corruption, with Zambia scoring 39/100 on Transparency International’s index (92nd globally), continues to deter investment and increase transaction costs .

3. The Political Dimension: Democratic Testing and Constitutional Controversy

3.1 The Constitutional Amendment Debate

President Hichilema’s declaration that the Constitution would be amended before the August 2026 general elections has emerged as the central political controversy of Zambia’s electoral cycle. The announcement, described by one commentator as a “political bombshell,” has “pitted the promise of progress against the spectre of power plays” and triggered “a reckoning with Zambia’s democratic soul” .

The government’s rationale focuses on electoral integrity. Chief Government Spokesperson Cornelius Mweetwa explained that Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 7 aims to ensure Zambia enters the 2026 election with “a predictable and stable constitutional framework” . Under current provisions, he warned, the Electoral Commission of Zambia “could be forced to restart nominations if a presidential candidate were to withdraw close to election day—a scenario he warned could undermine peace, security, and the credibility of the electoral process” .

The bill also seeks to “refine provisions related to presidential election petitions, which previously caused legal uncertainty, particularly during the 2016 elections” . Mweetwa emphasized that Bill No. 7 contains “non-controversial amendments agreed upon by both ruling and opposition Members of Parliament during a 2023 consultative meeting” and does not “increase presidential powers or alter term limits” .

3.2 Critics and Constitutional Concerns

Despite government assurances, the amendment process has generated significant opposition. Media practitioner Kalumbu Lumpa notes that President Hichilema’s “vagueness, coupled with the assertion that ‘we have agreed,’ has left Zambians asking: agreed with whom? In a nation where trust in leaders is hard-earned, this opacity is a spark in a tinderbox” .

Opposition leaders have “wasted no time crying foul,” though Lumpa cautions that “their stance isn’t without its own contradictions,” as many “once championed constitutional tweaks when it suited them” . The more substantive critique comes from civil society. In March 2025, fourteen organizations led by the Zambia Council for Social Development rejected Hichilema’s timeline, urging “a post-2026 process rooted in national dialogue” and invoking Zambia’s 2016 success when “broad input birthed a document that most could claim as their own” .

Presidential candidate Kelvin Fube Bwalya has raised more fundamental concerns, warning that “recent constitutional amendments and digital security legislation had reshaped the electoral landscape in ways that risk weakening fairness and public confidence in governance systems” . He stressed that “democracy is not only about voting day” and that “fairness must be guaranteed well before ballots are cast” .

3.3 Democratic Trajectory and International Perception

Zambia’s democratic credentials have been tested during Hichilema’s tenure. The country “once earned continental admiration for a peaceful transition of power,” but now “faces growing concerns from both citizens and international observers regarding the integrity of the democratic environment” . Critics point to “arbitrary arrests of journalists and opponents” and “a lack of inclusiveness of growth” as evidence of democratic backsliding .

Coface’s analysis notes that while Hichilema is expected to win the August 2026 elections, “the victory of the ruling party may be less resounding than in the last elections, despite solid economic results, the prospect of an end to the crisis and the president’s image of integrity” . His reputation, the analysis suggests, “has been tarnished by arbitrary arrests of journalists and opponents, as well as by a lack of inclusiveness of growth” .

3.4 Electoral Context and Political Alignments

The August 13, 2026 general elections will test both Zambia’s democratic resilience and the political strength of the United Party for National Development (UPND). President Hichilema, who defeated incumbent Edgar Lungu in a landslide 2021 victory, seeks a second term. The main opposition Patriotic Front (PF), which governed from 2011 to 2021, “still facing criticism for its mismanagement of public finances, which led the country to default during the Covid crisis” .

The electoral landscape has been shaped by both constitutional amendments and digital security legislation. Bwalya has called for “a level electoral playing field, institutions that serve constitutional principles rather than political incumbency, and digital laws that protect citizens’ freedoms” while encouraging economic policies that improve household welfare .

At the diplomatic level, Zambia’s international partners continue to express support while watching developments closely. The Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, Somalia’s Ambassador Hawa Hassan Mohamed, praised Zambia for “its political stability, economic reforms and commitment to peaceful democratic governance” during the annual diplomatic greeting in January 2026 . Such endorsements provide international validation but may also signal a preference for continuity over disruption.

4. Regional Positioning: Between East and South

4.1 The EAC Question: Membership or Partnership?

Zambia is not a member of the East African Community, yet its relationship with the bloc is increasingly significant. As President Hichilema articulated during the Ghana-Zambia business dialogue, his vision encompasses “building enduring bridges between Zambia, Ghana, ECOWAS, SADC, East African Community and north African community” . This framing positions Zambia as a connector between regional formations rather than exclusively aligned with any single bloc.

Several factors explain Zambia’s growing engagement with East Africa:

Geographic Logic: Zambia’s northeastern border with Tanzania places it in direct proximity to EAC territory, creating natural trade and transport linkages. The port of Dar es Salaam serves as a critical gateway for Zambian imports and exports, particularly through the TAZARA railway.

Infrastructure Integration: As detailed below, major infrastructure initiatives—the Lobito Corridor to the Atlantic, TAZARA rehabilitation to Dar es Salaam—position Zambia to utilize both eastern and southern routes, reducing dependence on any single corridor.

Energy Cooperation: Zambia participates in the Southern African Power Pool, which includes EAC members, and collaborates with Tanzania on grid interconnection projects that facilitate power trade.

Investment Flows: East African investors, particularly from Kenya and Tanzania, have increasing presence in Zambian markets, while Zambian firms explore opportunities in the region.

However, formal EAC membership remains unlikely in the near term. Zambia’s institutional commitments to SADC and COMESA, its distinct economic structure, and the absence of a compelling political driver for accession suggest that “strategic partnership” rather than “membership” will characterize the relationship for the foreseeable future.

4.2 The Lobito Corridor: Atlantic Gateway and Regional Integration

The Lobito Corridor development represents one of Africa’s most ambitious infrastructure initiatives and a strategic priority for Zambia. In February 2026, Ministers from Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Zambia agreed on “concrete steps to accelerate development of the Lobito Corridor” following a high-level coordination meeting in Luanda opened by Angolan President João Lourenço .

The corridor is conceived not merely as a transport route but as “a fully integrated economic corridor; capable of catalyzing agriculture, SME development, value-added mining, energy, and urban growth, while strengthening access to global markets through the Atlantic Ocean” . Home to more than 30 million people across the three host countries, the corridor stands “at the center of our shared ambition to deepen regional integration, diversify our economies, and translate connectivity into jobs, investment, and rising incomes” .

Key outcomes from the Luanda meeting include:

-

Lobito Corridor Development Master Plan: A shared implementation framework to support milestone tracking and systematic follow-up

-

Joint Investment Platform: Designed to mobilize public and private capital at scale for transport, logistics, and productive investments

-

Trade Facilitation Reforms: Commitments to streamline procedures, reduce bottlenecks, and improve movement of goods and people

-

Enhanced Coordination: Strengthened support for the Lobito Transport Trade Facilitation Agency, with the DRC selected to host the second coordination meeting

Zambia’s Finance Minister Situmbeko Musokotwane emphasized the corridor’s strategic importance: “For Zambia, the Lobito Corridor is a strategic priority. It will diversify our exports, lower transport and logistics costs, and provide our producers with more efficient access to the Atlantic, strengthening competitiveness in mining, agriculture, and value-addition industries” .

4.3 Eastward Infrastructure: TAZARA and Energy Integration

While the Lobito Corridor opens Atlantic access, Zambia simultaneously pursues eastward infrastructure integration. The TAZARA railway, connecting Kapiri Mposhi in Zambia to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, is undergoing rehabilitation with support from development partners. This route provides critical access to Indian Ocean trade and directly links Zambia to the East African transport network.

Energy integration with Tanzania is advancing through grid interconnection projects that will facilitate power trade and enhance energy security. These initiatives complement broader regional cooperation through the Southern African Power Pool, which includes both SADC and EAC members.

The Zambezi River Authority’s decision to increase water allocation for power generation to 30 billion cubic metres for 2026—shared equally between Zambia and Zimbabwe—supports energy stability for both countries . The Batoka Gorge Hydro-Electric Scheme, a priority bilateral project with capacity of 2,400 megawatts, is expected to “drive industrialisation, job creation and economic growth” . The Zimbabwe–Zambia–Botswana–Namibia (ZIZABONA) transmission project will provide “an alternative power wheeling route between Zambia and Zimbabwe,” easing constraints and enhancing power trading .

4.4 Bilateral Partnerships: Ghana, DRC, and Beyond

Zambia’s regional strategy extends beyond corridor development to active bilateral partnership building. The February 2026 elevation of relations with Ghana to “a comprehensive economic partnership” exemplifies this approach . President Hichilema and President Mahama committed to “enhancing private sector participation, facilitating the movement of goods and capital, and promoting joint ventures for value addition, industrial development and job creation” .

Priority cooperation areas include:

-

Agriculture and food systems transformation, with focus on agro-processing and value addition

-

Energy cooperation, particularly renewable energy and power trade

-

Trade and investment promotion

-

Financial technology and digital financial services

The partnership has already generated tangible results: business transactions valued at $7 million concluded between Zambian and Ghanaian fintech companies during a joint business forum, with ongoing negotiations estimated at $65 million potentially generating about 8,000 jobs in both countries .

With the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia maintains close relations on security and mining trade, reflecting the integrated nature of the copper belt economy. With Tanzania, cooperation focuses on energy and logistics projects. Relations with Malawi, Angola, and Mozambique remain stable, centered on cross-border trade and infrastructure.

4.5 Continental Vision: AfCFTA and Intra-African Trade

President Hichilema’s regional vision is framed within broader continental aspirations. His call to “build enduring bridges between Zambia, Ghana, ECOWAS, SADC, East African Community and north African community” reflects commitment to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and the goal of a single continental market .

Crucially, Hichilema emphasizes that intra-African trade is not pursued at the expense of extra-continental partnerships: “When we talk about intra-African trade, we are not against Europe, America or Asia. Africa will be better placed to do business with Europe, America or Asia when it’s organised. That’s all we are talking about” . This framing positions regional integration as complementary to global engagement—a “platform” for more effective international economic relations.

5. The Integration-Fragmentation Paradox

5.1 Economic Stabilization vs. Democratic Legitimacy

Zambia’s current trajectory reveals a fundamental tension between economic stabilization and democratic legitimacy. The same government that has successfully navigated debt restructuring, restored IMF relationships, and attracted renewed investment faces accusations of democratic backsliding through rushed constitutional amendments, arbitrary arrests, and insufficiently inclusive governance.

This tension carries material consequences. As investment analysis increasingly recognizes, “diplomatic signals influence credit committees, insurance premiums and sovereign risk assessments” . Perceptions of democratic erosion can offset gains from economic reforms, increasing borrowing costs and reducing investment attractiveness.

The government appears to calculate that economic performance will outweigh governance concerns in both domestic electoral calculations and international partner assessments. Whether this calculus proves correct depends on the severity of democratic criticisms, the responsiveness of international actors, and the ability of opposition and civil society to mobilize domestic and external pressure.

5.2 Eastern vs. Southern Orientations

Zambia’s geographic position enables strategic diversification between eastern and southern regional orientations, but this flexibility also creates complexity. Simultaneous investments in the Lobito Corridor (Atlantic, western orientation), TAZARA rehabilitation (Indian Ocean, eastern orientation), and southern routes through Zimbabwe and South Africa require coordination across multiple frameworks and partners.

The risk lies in overextension—committing to multiple corridors without achieving critical mass in any single route. The opportunity lies in leveraging competition among corridors to secure favorable terms from each. As global investors and development partners back competing infrastructure visions, Zambia’s ability to extract maximum benefit depends on skillful negotiation and clear strategic prioritization.

5.3 Resource Wealth vs. Inclusive Development

The structural challenge of translating resource wealth into broad-based development persists. Copper revenues support macroeconomic stabilization and debt service, but poverty remains entrenched at 62 percent . Growth has not generated sufficient employment or improved living conditions for the most vulnerable.

This disconnect between macroeconomic indicators and household realities creates political vulnerability. Opposition voices, including presidential candidate Bwalya, emphasize the need to “translate economic recovery into tangible benefits for citizens” . The Hichilema administration’s ability to demonstrate inclusive growth before the August 2026 elections may prove as important as its macroeconomic achievements.

5.4 Regional Integration vs. National Sovereignty

Zambia’s pursuit of multiple regional partnerships requires navigating tensions between integration commitments and national policy space. Participation in SADC, COMESA, and the AfCFTA involves aligning regulations, harmonizing standards, and accepting dispute resolution mechanisms that constrain unilateral action. Infrastructure corridor development creates interdependence that limits policy flexibility.

The government’s approach—active engagement across multiple frameworks while maintaining clear national priorities—reflects recognition that integration is a tool for achieving national objectives rather than an end in itself. President Hichilema’s framing of “building enduring bridges” positions regional partnerships as instruments for Zambian development, not substitutes for national strategy.

6. Conclusion: The Pivot State

Zambia’s economic and political status at the intersection of Eastern and Southern Africa reflects the strategic positioning of a state that has emerged from crisis into a period of opportunity defined by profound tensions. Economically, the country has achieved remarkable stabilization: debt restructuring advanced, IMF relationships restored, growth accelerating to nearly 6 percent, and inflation moderating. These achievements represent hard-won credibility with international partners and create foundations for sustained expansion.

Yet structural vulnerabilities persist. Copper dependence leaves the economy exposed to price volatility and Chinese demand fluctuations. Climate vulnerability threatens power generation and agricultural production. Poverty at 62 percent demonstrates that macroeconomic recovery has not translated into broad-based improvements in living standards. The investment climate, while improved, remains constrained by underdeveloped credit systems, workforce gaps, and corruption.

Politically, Zambia approaches a critical test. The August 2026 elections will occur amid contentious constitutional amendments, concerns about democratic backsliding, and debates about the inclusiveness of governance. President Hichilema’s push for pre-election constitutional changes has generated fierce controversy, with civil society and opposition warning of damage to democratic institutions. The government’s framing of amendments as necessary for electoral integrity competes with narratives of self-interested power consolidation.

Regionally, Zambia occupies a unique position as a pivot between Eastern and Southern Africa. Infrastructure investments in both the Lobito Corridor (Atlantic) and TAZARA railway (Indian Ocean) create options and reduce dependence on any single route. Energy integration through the Southern African Power Pool and bilateral projects with Tanzania deepens interdependence with East African partners. Yet Zambia remains institutionally anchored in SADC and COMESA, with EAC membership unlikely in the near term.

Several conclusions emerge for understanding Zambia’s status in relation to East Africa:

First, Zambia matters to East Africa as a corridor partner and market. The TAZARA railway and grid interconnection create structural interdependence that benefits both sides. As EAC members seek diversified trade routes and energy security, Zambia’s eastward orientation offers mutual advantage.

Second, Zambia’s economic recovery demonstrates pathways relevant to East African partners facing debt challenges. The G20 Common Framework process, while imperfect, offers lessons for crisis resolution. The combination of IMF engagement, creditor coordination, and domestic reform provides a template for restoring credibility.

Third, Zambia’s democratic tensions echo challenges facing several EAC members. Debates about constitutional amendments, electoral integrity, and political space resonate across the region. How Zambia navigates these tensions will inform regional discussions about governance standards and democratic resilience.

Fourth, Zambia’s positioning between eastern and southern orientations illustrates the complexity of overlapping regional memberships in Africa. As the continent pursues integration through multiple frameworks, states like Zambia demonstrate both the opportunities and challenges of strategic diversification.

The path forward requires managing the tensions inherent in simultaneous recovery, reform, and integration. Economic stabilization must translate into inclusive development that reaches the 62 percent living in poverty. Democratic institutions must accommodate debate while maintaining stability. Infrastructure investments must achieve critical mass across multiple corridors. Regional partnerships must deliver tangible benefits while preserving policy space.

President Hichilema’s framing captures both the aspiration and the challenge: building “enduring bridges” that connect Zambia to multiple regional partners while ensuring that the bridges serve Zambian development. For East Africa, Zambia represents a strategic partner whose trajectory—economic, political, and regional—will influence the broader landscape of African integration. The pivot state’s choices matter not only for its own citizens but for the shape of regional cooperation across eastern and southern Africa.

References

-

Ecofin Agency. (2026, January 30). IMF Forecasts Zambia Growth at 5.8% in 2026 as Power and Mining Output Rise. https://www.ecofinagency.com/news/3001-52438-imf-forecasts-zambia-growth-at-5-8-in-2026-as-power-and-mining-output-rise

-

Legalbrief. (2026, January 3). Zambia democracy at risk with planned changes. https://legalbrief.co.za/diary/legalbrief-africa-new/story/concerns-for-democracy-over-zambias-planned-changes/print/

-

State House Zambia. (2026, February 6). Let’s build enduring bridges of trade as Africans – President Hichilema. https://www.sh.gov.zm/lets-build-enduring-bridges-of-trade-as-africans-president-hichilema/

-

ZNBC. (2026, January 29). Zambia Calls for Increased Intra-African Trade. https://znbc.co.zm/?p=10847

-

Coface. (2025, October). Zambia: Economic Risk & Country Profile Analysis. https://www.coface.uk:443/news-economy-and-insights/business-risk-dashboard/country-risk-files/zambia

-

Zambian Eye. (2026, February 17). Recent constitutional amendments undermine Zambia’s long history of peaceful transition of power- KBF. https://zambianeye.com/recent-constitutional-amendments-undermine-zambias-long-history-of-peaceful-transition-of-power-kbf/

-

Ministry of Finance and National Planning, Zambia. (2026, February 6). ANGOLA, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO, AND ZAMBIA AGREE ON CONCRETE STEPS TO ACCELERATE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LOBITO CORRIDOR. https://www.mofnp.gov.zm/?p=8532

-

Xinhua. (2026, February 6). Zambia, Ghana elevate ties to comprehensive economic partnership. https://english.news.cn/20260206/3d448de068e14dcfaf19e23b0e993f2e/c.html

-

ZNBC. (2025, December 3). Cabinet Approves Return of Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 7 Ahead of 2026 Elections. https://znbc.co.zm/?p=9493

-

ZNBC. (2025, December 29). Water Allocation Increased for Energy Stability. https://znbc.co.zm/?p=10239