This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) economic and political status as of early 2026. It finds a nation exhibiting a profound dichotomy: while macroeconomic indicators show remarkable progress with controlled inflation, sovereign credit rating upgrades, and planned diversification of public financing, the political and security landscape remains critically fragile. The eastern provinces are mired in a complex conflict involving the M23 rebellion, regional armed groups, and internationalized tensions, which directly undermines economic stability and imposes significant security expenditures. The paper examines the DRC’s recent economic achievements, including fiscal reforms and mining sector growth, alongside persistent challenges such as revenue leakage. It then dissects the political dynamics, focusing on the M23 conflict, regional and international mediation efforts, and the beleaguered UN peacekeeping mission. The analysis concludes that the DRC’s future trajectory hinges on the government’s ability to reconcile its macroeconomic ambitions with the urgent need for a political solution to the eastern conflict, a prerequisite for inclusive and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) stands at a critical juncture in 2026, embodying a stark contrast between economic promise and political peril. As Africa’s second-largest country by landmass and a state endowed with mineral resources critical to the global energy transition, the DRC’s stability is of paramount importance to the Great Lakes region and the international community. This paper presents a deeply researched analysis of the nation’s current status, drawing upon the latest reports from governmental sources, international financial institutions, credit rating agencies, and regional news outlets from the first quarter of 2026.

The central finding of this research is the existence of a “two-speed” Congo. On one hand, the macroeconomic framework shows signs of maturation: inflation has been tamed from hyperinflationary levels, foreign currency reserves are robust, and international investors are showing renewed interest . On the other hand, the political and security situation in the eastern provinces—North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri—has deteriorated into a protracted humanitarian and geopolitical crisis that directly threatens the nation’s fiscal health and territorial integrity .

2. Economic Status: Macroeconomic Stabilization and Structural Vulnerabilities

The economic profile of the DRC in early 2026 is characterized by a successful stabilization program juxtaposed against deep-seated structural challenges, particularly its overwhelming dependence on the mining sector.

2.1. Macroeconomic Performance and Outlook

The DRC has achieved notable macroeconomic stability. According to the Central Bank of Congo (BCC), the weekly inflation rate slowed to 0.15% as of mid-January 2026, reflecting a continued slowdown in price formation following the post-holiday normalization of demand . This represents a dramatic deceleration from the 23.6% inflation recorded in 2023, with the rate falling to approximately 2% in 2025, well below the central bank’s 7% target . The BCC has been able to gradually reduce its key policy rate to 15% in January 2026, down from a peak of 25% in August 2023, signaling increased confidence in price stability .

Growth projections remain robust. S&P Global Ratings projects real GDP growth to average a strong 5% annually through 2028, driven by sustained global demand for copper and cobalt . This performance is expected to outperform most peer countries. The economy has expanded by more than 40% since 2020, with exports now accounting for 50% of GDP—double the level seen in 2019 .

2.2. Fiscal Reforms and International Creditworthiness

The government of Prime Minister Judith Suminwa has received plaudits from international financial institutions for its fiscal discipline. In a significant development, S&P Global Ratings revised the DRC’s outlook from “stable” to “positive” in January 2026, while affirming its long-term sovereign credit rating at ‘B-‘ . This revision was attributed to robust growth, a consolidation of foreign exchange reserves (which reached $7.9 billion at the end of 2025, covering three months of imports), and improved tax collection through ongoing fiscal reforms .

Key reforms cited by the IMF and S&P include the launch of a standardized electronic billing system in December 2025 to boost VAT collection, the elimination of ad hoc tax exemptions for mining companies, and reductions in fuel subsidies . These measures have helped sustain government revenue at 14-15% of GDP, a significant increase from the 11% average of the past decade .

This improved fiscal credibility is paving the way for the DRC’s entry into international capital markets. The nation plans to raise approximately $750 million in April 2026 through its inaugural Eurobond issuance, intended to finance infrastructure projects .

2.3. The Mining Sector: Dominance and Reform

The mining sector remains the undisputed engine of the Congolese economy. Annual copper production is expected to reach 3.3 million tons in 2025, tripling the output from a decade ago . However, this dominance comes with the challenge of revenue leakage. An IMF report published in January 2026 revealed a startling statistic: studies show the DRC loses nearly half of its potential mining revenues due to insufficient controls over volumes and the content of valuable metals .

In response, authorities are planning to deploy automated weighing and quality-control systems by March 2026. These measures include truck weighing scales and non-intrusive quality-control mechanisms to improve measurement accuracy at export points. A new mineral analysis laboratory is also being operationalized under the tax administration to verify declared values .

2.4. Financial Sector Modernization

Efforts to modernize the financial sector are underway. Financial inclusion has risen from 38.5% in 2022 to 50% currently, primarily driven by mobile payment solutions . A landmark development is the planned launch of an interbank electronic payments group by the end of March 2026, supported by the International Finance Corporation (IFC). This body will ensure interoperability between banks and mobile money operators, manage shared infrastructure like the national electronic payment switch, and set security standards .

Concurrently, the Central Bank of Congo is tightening oversight of bank liquidity. New regulations expected by June 2026 will require banks to submit detailed recovery and resolution plans, including stress tests for the loss of correspondent banking relationships—a significant vulnerability given the DRC’s continued presence on the FATF grey list .

3. Political Status: Conflict, Mediation, and Governance Challenges

While the macroeconomic picture shows improvement, the political and security environment remains the DRC’s Achilles’ heel. The eastern provinces are engulfed in a complex conflict that has drawn in regional states and international powers.

3.1. The Resurgence of the M23 and the Eastern Crisis

The most significant security challenge is the renewed activity of the March 23 Movement (M23). Following a lightning advance in late 2025, the group captured major cities, including Goma and Bukavu. In December 2025, M23 fighters seized the key trading hub of Uvira on Lake Tanganyika, withdrawing a week later under US pressure . The damage was extensive; upon returning in mid-January 2026, local officials found government offices ransacked, with windows smashed and files destroyed, illustrating the breakdown of state authority .

The conflict has created a severe humanitarian crisis, with hundreds of thousands displaced. The UN has documented over 7,000 deaths in the eastern provinces of North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri since the escalation began, alongside systematic sexual violence and the recruitment of child soldiers .

3.2. Regional and International Mediation Efforts

The conflict has become deeply internationalized. The Angolan Head of State and pro tempore head of the African Union, João Lourenço, has played a prominent role in mediation, hosting talks in Luanda in February 2026 with the leaders of the DRC, Togo, and a former Nigerian president to analyze the latest developments and promote a lasting agreement . The President of Togo, Faure Gnassingbé, has been formally appointed as the African Union mediator for the conflict .

Parallel tracks of diplomacy are also active. In December 2025, the DRC and Rwanda signed the US-mediated “Washington Agreements for Peace and Prosperity,” alongside complementary accords focused on mining investment and regional economic integration . Qatar has also indicated its intention to invest up to $21 billion as part of a separate peace process involving the M23 .

Despite these efforts, a ceasefire agreed upon in October 2025 remains fragile. The M23’s political leader, Bertrand Bisimwa, accused the government in February 2026 of violating the truce by bombing their positions, stating, “The results so far are satisfying, even though what we have signed so far has no real impact on the ground” .

3.3. The M23’s Political Narrative: Federalism

The M23 is attempting to frame its armed struggle within a broader political discourse. In a February 2026 interview, Bisimwa explicitly stated the group advocates for federalism, not secession. He argued that over 60 years of unitarism has failed the vast and diverse nation, calling it “a system that is not working” . He drew comparisons to the United States and Nigeria, suggesting federalism would reinforce national unity by allowing regions to manage their affairs while answering to a central government. This rhetorical shift represents an attempt to gain political legitimacy and presents a complex challenge for Kinshasa, which must now contend with an armed group that is also articulating a constitutional reform agenda .

3.4. The Role of MONUSCO and Regional Forces

The UN peacekeeping mission, MONUSCO, finds itself in a precarious position. Its mandate was renewed by the Security Council until December 2026, even as its effectiveness is widely questioned . Analysts from the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) argue that MONUSCO’s rigid mandate and operational constraints have rendered it misaligned with the realities on the ground. The mission is limited to operating within the DRC, even though the conflict is fueled by cross-border dynamics involving Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi. Poor intelligence sharing and a lack of joint planning with regional actors create gaps that armed groups exploit .

The mission has also become a political lightning rod. It is often blamed for the failures of the Congolese army, which bears primary responsibility for protecting civilians. Anti-MONUSCO sentiment has become a useful political tool for local actors. As one analyst noted, “MONUSCO replicates general peacekeeping aims without sufficiently adapting to the DRC context” . The departure of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) mission, SAMIDRC, further complicates the security landscape .

4. The Interplay Between Economy and Politics

The security crisis in the east imposes a direct and significant economic cost. S&P Global estimates that security spending consumes about 3.4% of GDP annually . This expenditure diverts resources from development and infrastructure projects, undermining the government’s goal of creating a more diversified and inclusive economy.

The conflict also poses a reputational risk that could derail the DRC’s emerging market ambitions. National Deputy Éric Tshikuma, a member of the Ecofin commission, explicitly warned that the “negative impact of the Rwandan aggression and its M23/AFC auxiliaries on the national economy is a decisive risk that could hinder the path to sustainable and inclusive growth” . While the positive outlook from S&P is a “strong signal of economic credibility,” it remains contingent on the government’s ability to manage these security risks. The planned $750 million Eurobond issuance in April 2026 will serve as a critical barometer of investor confidence in the face of ongoing instability .

5. Conclusion

The Democratic Republic of the Congo in early 2026 presents a study in contrasts. On the economic front, the government has made commendable strides in stabilizing the macroeconomy, reining in inflation, bolstering reserves, and implementing fiscal reforms that have earned it international credibility. The mining sector continues to attract investment, and plans to tap international bond markets signal a desire to finance future growth.

However, these economic achievements are built on fragile ground. The entrenched conflict in the eastern provinces, characterized by the M23 rebellion, regional power struggles, and a dire humanitarian situation, casts a long shadow over the nation’s future. The conflict not only inflicts immediate human suffering but also siphons off public funds, deters investment in non-extractive industries, and threatens the very territorial integrity required for a functioning state.

The path forward demands a dual-track approach. The government must continue its prudent economic management to build the fiscal resources needed for long-term development. Simultaneously, it must urgently and credibly engage in the political processes mediated by the African Union and others to address the root causes of the eastern conflict—including issues of governance, marginalization, and regional security cooperation. The DRC’s ability to resolve this dichotomy will determine whether it emerges as a Central African powerhouse or remains a nation perpetually defined by its unrealized potential.

References

-

Ministère des Finances, du Budget et du Portefeuille Public. (2025, December 21). Vote de la Loi de finances 2026. Finances.gouv.cg.

-

Angop. (2026, February 9). Peace in eastern DRC analyzed again in Luanda. Angop.ao.

-

Agence Congolaise de Presse (ACP). (2026, January 21). DRC: weekly inflation rate slows to 0.15%. acp.cd.

-

TimesLIVE. (2026, February 13). Mayor sets up staff in DRC’s looted Uvira after 2025 capture. TimesLIVE.co.za.

-

Ecofin Agency. (2026, January 23). DR Congo Plans Tighter Oversight of Mining Exports in 2026. Ecofinagency.com.

-

Agence Congolaise de Presse (ACP). (2026, January 29). Public finances: national elected official praises government’s efforts in macroeconomic stabilization. acp.cd.

-

The EastAfrican. (2026, February 14). M23: We’re advocating federalism not cessation, in the vast, diverse DRC. Theeastafrican.co.ke.

-

Investing.com Brasil. (2026, January 23). Perspectivas da República Democrática do Congo revisadas para positivas pela S&P. br.investing.com.

-

Mooloo, N. (2026, January 12). MONUSCO’s rigid mandate hinders civilian protection in eastern DRC. ISS Africa.

-

Kabeya, B. (2026, January). Interbank electronic payments group launch planned in DRC by end-March 2026. Bankable.africa.

Related Posts

The Economic and Political Status of Malawi

Abstract This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of Malawi's contemporary…

The Economic and Political Status of Zimbabwe in East Africa

Abstract This paper examines Zimbabwe's contemporary economic and political status,…

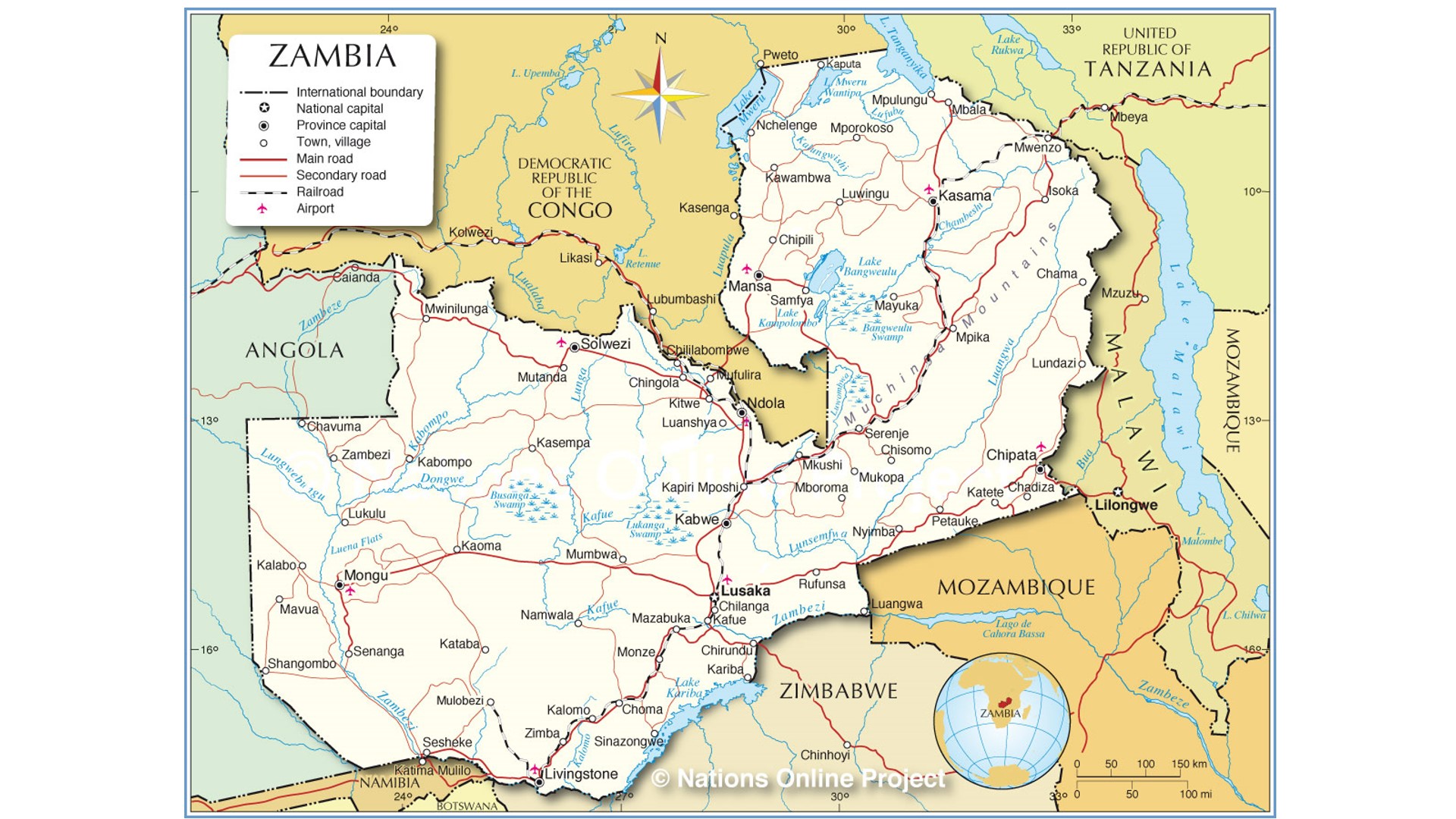

Zambia’s Contemporary Economic and Political Status

Abstract This paper examines Zambia's contemporary economic and political status,…