Abstract

This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the economic and political status of Niger in the context of West Africa as of early 2026. Following the July 2023 coup d’état, Niger has undergone a profound transformation. Economically, the country is experiencing a hydrocarbon-fueled boom, with GDP growth surging to over 8% in 2024, driven by the commencement of large-scale oil exports . However, this growth is juxtaposed against deep structural vulnerabilities, including extreme poverty, food insecurity, and a landlocked geography that complicates trade . Politically, the junta has consolidated power, dissolving democratic institutions and orchestrating a sharp geopolitical realignment away from traditional Western partners like France and the United States toward Russia . This realignment is symbolized by the formation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) and a contentious withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) . This paper argues that while the military regime has leveraged resource nationalism to assert sovereignty and achieved short-term economic gains, it faces critical challenges related to diplomatic isolation, security sector governance, and the long-term sustainability of its economic model.

Introduction: Niger at a Crossroads

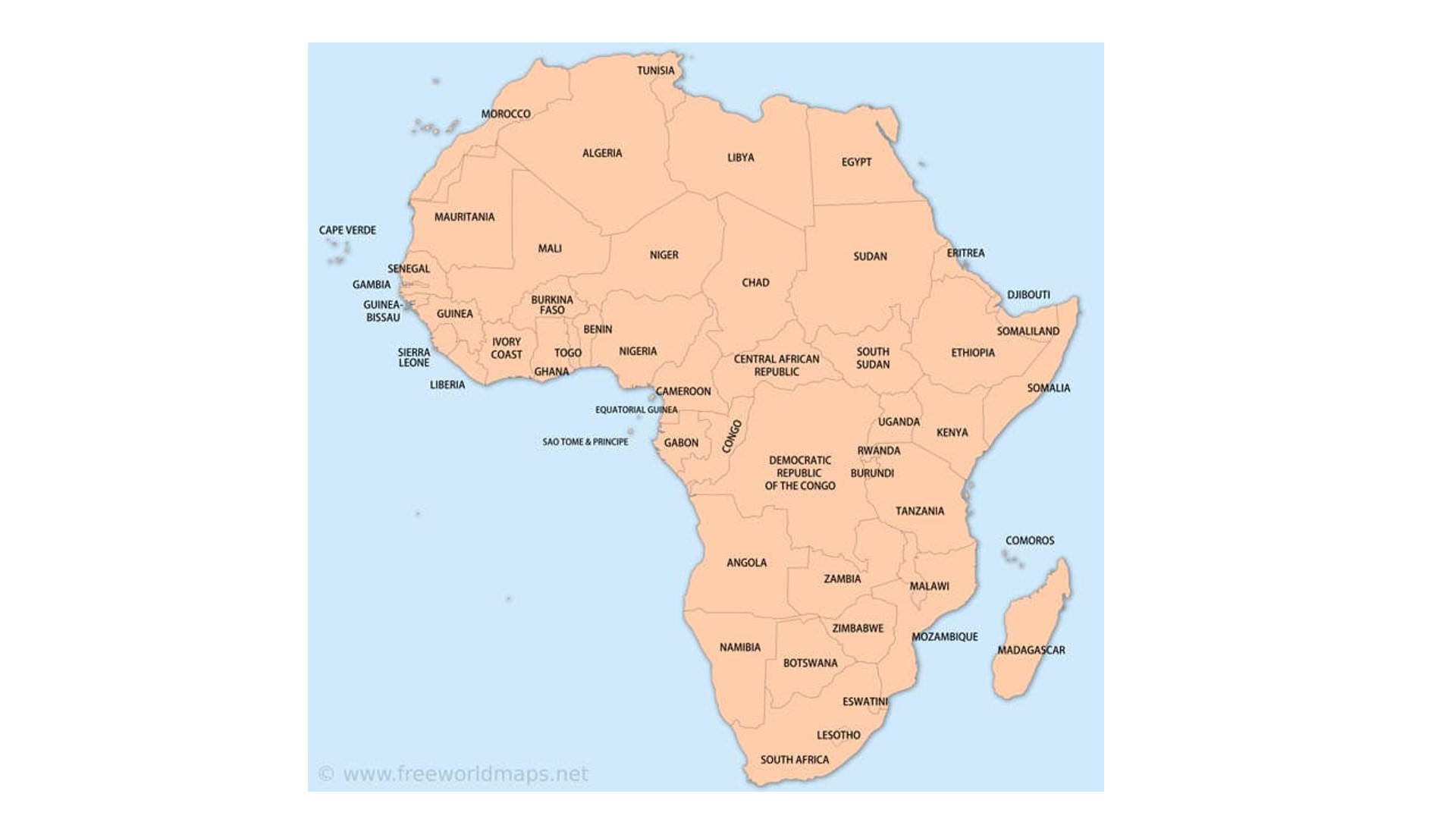

The Republic of Niger, a landlocked nation in the heart of the Sahel, has long been defined by its paradoxes. It possesses significant mineral wealth—including uranium, gold, and newly exploited oil reserves—yet consistently ranks at the bottom of the Human Development Index . As a linchpin in regional security architectures, it has hosted Western military bases to combat jihadist insurgencies, while its own citizens face chronic poverty and climate shocks. The military coup of July 26, 2023, which osted democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum, shattered the country’s fragile democratic trajectory and ushered in a new era of military governance . This paper examines the resultant shifts in Niger’s economic structure and political orientation, exploring how the regime of General Abdourahamane Tiani is navigating the dual pressures of asserting national sovereignty and managing a complex economic transition.

1. The Economic Landscape: Oil-Fueled Growth Amidst Structural Frailty

Niger’s economy is currently defined by a dramatic divergence between strong macroeconomic growth figures and persistent structural weaknesses that affect the majority of its population.

1.1. The Oil Sector as a Primary Growth Engine

The cornerstone of Niger’s recent economic performance is the extraction and export of crude oil. In 2024, the economy rebounded sharply, with the World Bank reporting a growth rate of 8.4%, a significant increase from 2% in 2023 . This acceleration is almost entirely attributable to the start of large-scale oil exports via a new pipeline to Benin . By 2025, the sector was approaching its maximum capacity of approximately 110,000 barrels per day . This hydrocarbon boom has directly contributed to narrowing twin fiscal and current account deficits .

Future Outlook: The outlook for the sector includes the commissioning of a new mega-refinery in partnership with a Canadian group, aimed at reducing domestic dependence on imported petroleum products by 2026 . Additionally, while uranium exports have faced logistical hurdles due to border closures with Benin, new mining projects, such as the Dasa mine, are exploring alternative export routes via Algeria and Togo, indicating a resilient, if complicated, mining sector .

1.2. Agriculture: The Backbone of Livelihoods

Despite the fanfare surrounding oil, the agricultural sector remains the true backbone of Nigerien society, accounting for approximately 40% of GDP and employing 80% of the workforce . The sector’s performance is heavily dependent on rainfall, making it highly vulnerable to climate shocks. The strong agricultural harvest in 2024, aided by favorable weather, was crucial in moderating inflation and reducing extreme poverty . However, the sector’s reliance on rain-fed agriculture remains a critical point of fragility. To mitigate this, the government, with support from the World Bank’s Large-Scale Irrigation Program, is working to expand irrigated land, aiming to reduce vulnerability and stabilize yields .

1.3. Enduring Structural Vulnerabilities

Niger’s economic status in West Africa remains one of deep fragility. The country is landlocked, creating a dependency on its neighbors—particularly Benin for oil exports and Nigeria for 70% of its electricity supply—for access to international markets . Political tensions with Benin since the coup have repeatedly threatened this access, freezing some export corridors . Domestically, the economy is characterized by a large informal sector (approximately 60% of GDP), limited access to credit, and a population living in significant poverty, with a rate of 52% recorded in 2023 . Furthermore, the World Bank and IMF downgraded Niger’s debt sustainability rating from moderate to high in 2024, citing a rapid accumulation of arrears and a reliance on short-term borrowing .

Table 1: Key Economic Indicators for Niger (2023-2026)

| Indicator | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 (e/f) | 2026 (f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP Growth (%) | 2.0 – 2.6 | 8.4 – 10.3 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| Inflation (Annual Average, %) | 3.7 | 9.0 – 9.1 | 4.0 | 3.0 |

| Budget Balance (% of GDP) | -4.5 to -5.4 | -4.3 | -3.0 to -4.0 | -3.0 to -4.0 |

| Public Debt / GDP (% of GDP) | 51.8 | 47.2 – 47.5 | 42.5 – 45.0 | 41.5 |

| Current Account Balance (% of GDP) | -9.5 to -13.9 | -5.4 to -6.2 | -3.5 to -4.0 | -4.0 to -5.5 |

Note: Figures represent ranges or estimates from Coface and World Bank data .

2. The Political Earthquake: From Democracy to Military Rule

The political status of Niger has been fundamentally redefined by the 2023 coup, which reversed the country’s first peaceful transfer of power and initiated a period of authoritarian consolidation.

2.1. The Consolidation of the Junta

Following the coup, General Abdourahamane Tiani established the National Council for the Salvation of the Homeland (CNSP) and dissolved all democratic institutions . In March 2025, a new transitional charter was enacted, swearing in General Tiani as president for a five-year transition period, effectively resetting the clock on a return to civilian rule until 2030 . The charter also dissolved all 172 existing political parties, centralizing power and eliminating avenues for political pluralism . This has led international observers, such as Freedom House, to downgrade Niger’s status from “Partly Free” to “Not Free,” citing the junta’s restrictions on media freedom, due process, and the dissolution of elected local councils .

2.2. The Rupture with ECOWAS and the Formation of the AES

In a historic move, the junta announced Niger’s withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in January 2024, alongside its military-led neighbors, Mali and Burkina Faso . This act was a direct challenge to the regional bloc, which had imposed stringent sanctions and threatened military intervention to restore constitutional order. Niger’s leadership framed the withdrawal as a sovereign act against a body perceived as being influenced by former colonial powers . In its place, the three Sahelian nations have deepened their cooperation within the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), forming a joint military force of 5,000 troops to combat insurgencies and coordinate political and economic policies . While the withdrawal has created a formal political divide, Nigerian officials have noted that bilateral trade and relations, for instance through the Nigeria-Niger Joint Commission, have remained functional .

2.3. Geopolitical Realignment: From Paris to Moscow

The coup has catalyzed a dramatic geopolitical pivot. The junta has terminated long-standing military cooperation agreements with Western nations, ordering the departure of French and American troops who were previously key partners in the Sahel counter-terrorism mission . This vacuum has been filled by Russia, which has dispatched military equipment and personnel (Africa Corps) to Niger at the regime’s request . This realignment is not merely military but economic. The junta has adopted a strident resource nationalism, challenging French nuclear giant Orano’s operations, accusing it of violating shareholder agreements, and asserting greater state control over uranium and gold mining revenues .

3. Interconnected Challenges: Security, Sovereignty, and Human Rights

The political and economic trajectories of post-coup Niger are deeply interconnected with the persistent threat of insecurity and a deteriorating human rights environment.

3.1. The Security Imperative

General Tiani justified the coup by citing the previous government’s failure to address the deteriorating security situation . However, the threat from jihadist groups affiliated with ISIS and Al-Qaeda, particularly in the southwest near Burkina Faso and Mali and in the Lake Chad region, remains high . The new AES joint force represents an attempt to foster regional ownership of the security crisis. Yet, by pivoting away from Western intelligence and logistics, the junta is gambling on the effectiveness of its new Russian partnership to contain the violence that has displaced millions and destabilized the region.

3.2. The Cost of Rupture

The pursuit of “sovereignty” has come with tangible costs. The regime’s crackdown on civil society has led to the shutdown of numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs), resulting in significant job losses in a country with one of Africa’s highest youth unemployment rates . Arbitrary detentions of ousted officials, including President Bazoum, and restrictions on press freedom have drawn widespread condemnation from human rights groups, signaling a shrinking civic space . While the regime enjoys a degree of popular support for its anti-French stance, the economic hardships caused by sanctions and job losses in the aid sector are testing public patience .

Conclusion

As of 2026, Niger stands as a nation transformed. Its economic status is buoyed by oil wealth, offering a veneer of macro-economic stability that belies the deep-seated poverty and food insecurity experienced by its rapidly growing population. Its political status is defined by a resolute military junta that has traded democratic governance for assertive sovereignty, broken with its traditional regional partners in ECOWAS, and forged a new alliance with Russia. The success of this gamble remains highly uncertain. Niger’s future will depend on whether the regime can translate hydrocarbon revenues into inclusive development, effectively manage the security threat without its former partners, and navigate the complex diplomatic and economic terrain of a fragmented West Africa. For now, the country embodies the profound tensions of a region grappling with the allure of resource nationalism and the difficult realities of post-coup governance.

Sources:

- World Bank

- Democracy in Africa

- News24

- ReliefWeb

- Arise News

- Humanitarian Data Exchange

- Coface

- Freedom House

- com