Introduction: The Paradox of Vulnerability and Potential

Africa stands at the epicenter of one of the defining paradoxes of the 21st century: it is the continent most vulnerable to climate change, yet it holds the keys—in the form of abundant renewable energy resources and critical minerals—to a global green future. This article examines the profound and disproportionate impacts of climate change on Africa, juxtaposed against the contentious, high-stakes debate surrounding its energy transition. The central argument is that a successful transition in Africa is impossible without embedding the principle of climate justice at its core, requiring a fundamental restructuring of global finance, technology transfer, and energy equity.

Part I: The Multiplier Effect – Climate Change Impacts on Africa

Africa contributes less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet it suffers impacts that are both more severe and arrive faster than the global average. Warming in Africa is occurring at a rate approximately 1.5 times faster than the global mean (WMO, 2023).

1. Hydro-Climatic Shock: Water, Drought, and Flooding

- Megadroughts:Persistent drought, exacerbated by climate change, has pushed regions like the Horn of Africa into a state of near-permanent food crisis. The 2020-2023 drought, the worst in 40 years, led to the death of millions of livestock and pushed over 20 million into acute food insecurity.

- Devastating Floods:Conversely, increased atmospheric moisture leads to intense, unpredictable flooding. The 2022 Pakistan-level floods in South Africa (KwaZulu-Natal) and Nigeria, and the 2023 Libyan catastrophe following Storm Daniel, illustrate how aging infrastructure and rapid urbanization magnify the death toll and economic damage.

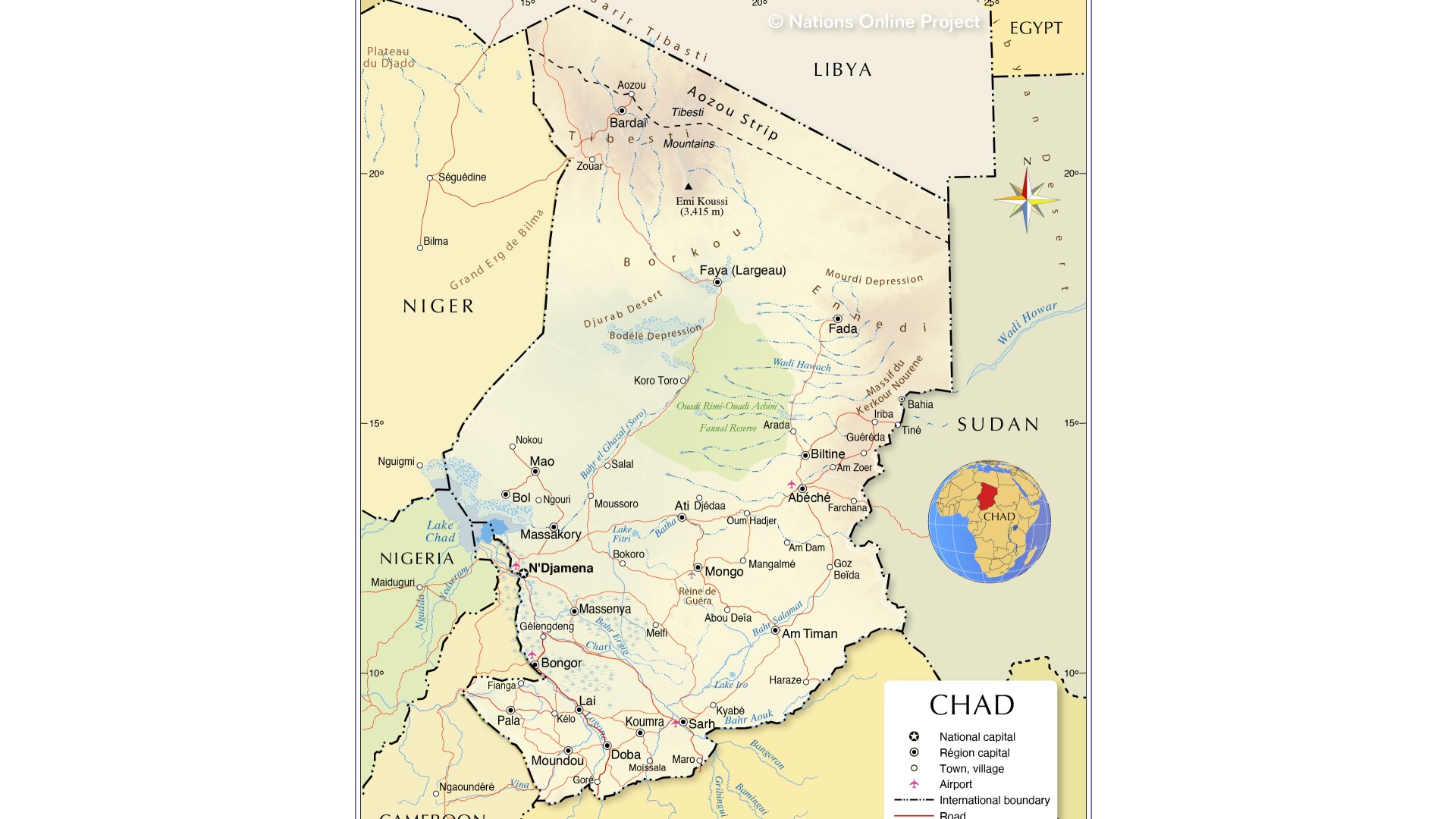

- Lake and River Basins in Crisis:Critical water bodies are shrinking. Lake Chad has diminished by 90% since the 1960s, displacing communities and fueling conflict. The Nile Basin faces increasing geopolitical tension as upstream and downstream nations grapple with variable flows.

2. Agricultural and Food System Collapse

African agriculture remains predominantly rain-fed. Climate change disrupts growing seasons, reduces crop yields (projected declines of up to 50% for staples like maize and wheat by 2050 in some regions), and promotes pest invasions. This directly threatens food sovereignty, increases malnutrition, and accelerates rural-to-urban migration, straining cities.

3. Health and Human Security

- Disease Vector Shift:Malaria and dengue fever are spreading to new, higher-altitude areas in East Africa as temperatures rise.

- Heat Stress:Urban heat islands in sprawling cities like Lagos and Kinshasa pose severe public health risks.

- Climate-Conflict Nexus:While not a direct cause, climate change acts as a “threat multiplier.” Resource scarcity (water, arable land) exacerbates existing tensions between farmers and herders in the Sahel and Sudan, and fuels recruitment by armed groups.

4. Economic and Developmental Reversals

The African Development Bank estimates Africa loses 5-15% of its GDP per capita growth annually due to climate change. Cyclones like Idai (2019) wipe out decades of infrastructure investment in hours. The cost of adaptation is staggering: the continent needs an estimated $50 billion annually by 2050.

Part II: The Just Energy Transition – Navigating a Minefield of Contradictions

The global imperative to move from fossil fuels to renewables presents Africa with a complex dilemma, framed by the concept of a Just Energy Transition (JET)—a shift that is fair, inclusive, and creates decent work, while leaving no one behind.

The African Position: Equity, Justice, and Energy Access

- The Right to Develop:Over 600 million Africans lack access to electricity, and 900 million lack clean cooking fuels. African nations argue they have a sovereign right to use their domestic fossil fuel resources (natural gas in particular) as a “bridge fuel” to industrialize, expand grid access, and alleviate energy poverty. They point to the historical emissions of the Global North and demand “carbon space.”

- The Gas Question:This is the most contentious issue. The EU’s classification of natural gas as a “green” investment (albeit temporarily) while urging Africa to skip it is seen as hypocritical. Countries like Mozambique, Tanzania, Nigeria, and Senegal view their vast gas reserves as critical for domestic power, industry, and export revenue.

- Financing the Leap:Africa’s renewable potential is unparalleled—over 60% of the world’s best solar resources, significant wind, geothermal, and hydropower. However, the cost of capital for renewable projects in Africa is 2-3 times higher than in developed nations. The existing climate finance architecture is inadequate, debt-laden, and skewed toward mitigation over adaptation.

Pillars of a Truly Just Transition for Africa:

- Sovereign Decision-Making:Transition pathways must be nationally determined, not externally imposed. South Africa’s JET-IP (Just Energy Transition Investment Plan, $98.7bn), supported by the International Partners Group (IPG), is a pioneering, if troubled, model of a country-led deal.

- Industrialization and Value Addition:The transition must not relegate Africa to a mere supplier of raw materials (cobalt, lithium, copper). It must include local beneficiation, manufacturing of solar panels and battery components, and building continental value chains. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could be a key enabler.

- People-Centered Approach:Phasing out coal in nations like South Africa must include robust plans for community reinvestment, worker retraining, and alternative livelihoods in mining regions. A just transition must address gender inequalities, as women often bear the brunt of energy poverty.

- Reformed Global Finance:Africa demands:

- Delivery of the long-promised $100 billion/yearin climate finance.

- Debt-for-climate swapsto free fiscal space.

- Concessional finance and guaranteesto de-risk and lower capital costs.

- Reform of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) to lend more for climate action.

- A functional Loss and Damage Fundwith African access.

Part III: Case Studies in Complexity

- South Africa (The JET Pioneer):Its coal-dependent economy (85% of electricity) and significant employment in coal value chains make its transition the world’s most watched. The $8.5bn IPG pledge faces challenges: community mistrust, grid constraints, and concerns over “green colonialism” if benefits are not local.

- Nigeria (The Gas Giant):Its Energy Transition Plan (ETP) envisions gas as the bedrock for stabilizing the grid and growing industry before a renewables ramp-up. It highlights the need for massive gas infrastructure investment alongside solar mini-grids.

- Kenya (The Renewable Leader):Generating over 90% of its power from renewables (geothermal, hydro, wind), Kenya demonstrates the technical feasibility of a green grid. Its challenge is managing climate vulnerability (drought affects hydropower) and financing universal access.

Part IV: The Geopolitical Dimension – A New Scramble?

Africa’s critical minerals and vast renewable potential have sparked a new geopolitical scramble. The EU’s Global Gateway, the US’s Prosper Africa and Minerals Security Partnership, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative all have green energy components. African agency is critical to ensure these competitions result in fair partnerships, not exploitative extraction.

Conclusion: Beyond Extraction, Toward Ecological Justice

The climate crisis and the energy transition in Africa are not merely technical or economic issues; they are fundamentally about justice, reparations, and a rebalancing of global power.

A successful Just Energy Transition for Africa would mean:

- Energy Sovereignty:Universal access powered by a decentralized, renewable grid.

- Climate-Resilient Development:Economies that thrive within planetary boundaries.

- A New Industrial Pathway:Leapfrogging to a green manufacturing hub.

Failure would mean entrenched poverty, heightened vulnerability, and a world that misses its climate goals by sacrificing equity.

The path forward requires the Global North to move beyond rhetoric and provide adequate, accessible finance and technology. For African leaders, it demands visionary governance that prioritizes long-term structural transformation over short-term extractive gains. The stakes are nothing less than the continent’s future stability, prosperity, and its right to define its own destiny in a warming world.

Sources:

- IPCC AR6 Reports, Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability(2022).

- African Development Bank (AfDB). African Economic Outlook 2022: Supporting Climate Resilience and a Just Energy Transition.

- IRENA & AfDB. (2022). Renewable Energy Market Analysis: Africa and Its Regions.

- Climate Policy Initiative. (2023). Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa.

- SA Presidency. (2022). Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP) for South Africa.

- (2021). Building Forward for an African Green Recovery.

- The Africa Climate Summit Nairobi Declaration(September 2023).