The Republic of Guinea, a West African nation of approximately 13.5 million people, occupies a paradoxical position in the regional landscape. It is endowed with some of the world’s most significant mineral resources—notably bauxite, iron ore, gold, and diamonds—yet remains one of the continent’s least developed countries. Its political trajectory, from authoritarian rule under Sékou Touré to tumultuous democratization and repeated military interventions, has profoundly shaped its economic fortunes. This paper provides a deeply researched analysis of Guinea’s contemporary economic and political status, arguing that the country exists in a state of perpetual transition, where immense resource wealth is consistently offset by governance failures, political instability, and entrenched poverty, leaving its potential largely untapped.

1. Introduction: The Colonial Legacy and the Weight of History

Guinea’s modern political economy is inextricably linked to its historical choices. In 1958, under the leadership of Ahmed Sékou Touré, it became the only French colony to reject membership in the French Community, opting instead for immediate independence. The famous retort, “We prefer poverty in liberty to riches in slavery,” set a defiant but economically costly precedent. France’s abrupt withdrawal of administrative personnel and capital, coupled with Touré’s subsequent 26-year rule (1958-1984) characterized by a centralized “command economy,” socialist austerity, and severe political repression, left the country isolated and impoverished. This foundational period established patterns of autocratic governance, economic mismanagement, and the use of resource nationalism as a political tool, patterns that continue to resonate today.

2. The Political Landscape: From Democratic Hope to Military Rule

Guinea’s political status is best described as unstable and in flux, with a powerful military acting as a recurrent political arbiter.

2.1 The Lansana Conté and Alpha Condé Eras: Illiberal Democracy

After Touré’s death, Lansana Conté seized power via a military coup, ruling from 1984 until his death in 2008. His tenure saw a shift towards structural adjustment and economic liberalization but remained marred by corruption, ethnic favoritism (toward his own Soussou group), and the erosion of state institutions. His death created a power vacuum filled by a military junta, which itself succumbed to violence and disorder.

The subsequent election of Alpha Condé in 2010, Guinea’s first democratic transfer of power, ignited hopes for a new era. A long-time opposition figure, Condé initially pursued reforms and attracted significant foreign investment in the mining sector. However, his rule gradually devolved into increasingly authoritarian practices. His manipulation of the constitution to run for a controversial third term in 2020, and his victory in an election widely condemned by the opposition, sparked widespread protests and violent crackdowns. Condé’s tenure underscored the persistence of the “big man” politics, where democratic institutions are hollowed out to maintain personal power, and deep ethnic fractures (primarily between the Malinké, from which Condé hailed, and the Peul, who comprise roughly 40% of the population) were exacerbated for political gain.

2.2 The 2021 Coup and the CNRD Junta

In September 2021, the cycle of instability culminated in a military coup led by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, who cited endemic corruption, poverty, and Condé’s constitutional manipulation as justifications. The Comité national du rassemblement et du développement (CNRD) dissolved the government and constitution. While initially met with popular jubilation from a populace weary of Condé’s rule, the junta has since entrenched its power. It has postponed a promised transition to civilian elections multiple times, engaged in repressive tactics against political opponents and journalists, and fractured the regional consensus by rejecting the ECOWAS-mandated 24-month transition timeline. As of early 2024, the political future remains uncertain, with elections tentatively slated for late 2025 but few signs of a genuine democratic opening.

3. The Economic Landscape: The “Geological Scandal” and the Paradox of Plenty

Guinea’s economy is a textbook case of the “resource curse,” where vast natural wealth fails to generate broad-based development.

3.1 Mining Sector Dominance and Structural Weaknesses

-

Bauxite Powerhouse: Guinea holds the world’s largest reserves of bauxite (the ore for aluminum). It is now the world’s second-largest producer (after Australia) and the top exporter to China, which relies heavily on Guinean supply. Major projects like Société Minière de Boké (SMB) and the CBG consortium are central to global aluminum supply chains.

-

Iron Ore Potential: The Simandou range, often called the “world’s largest untapped high-grade iron ore deposit,” represents a transformative potential. After decades of legal and political wrangling, a consortium including Rio Tinto, a Chinese consortium, and the Guinean government is finally advancing the $20+ billion project, which includes a 650km trans-Guinean railway. Its success could double Guinea’s GDP.

-

Gold and Diamonds: These sectors, while significant, are plagued by artisanal mining, smuggling, and limited formal revenue capture.

Despite this wealth, the mining sector operates largely as an enclave economy. Forward linkages (processing) are minimal—Guinea exports raw bauxite but refines little alumina domestically. Backward linkages (local procurement) are weak, and revenue management is opaque. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) has noted improvements in reporting but persistent gaps in how revenues are spent for public benefit.

3.2 Macroeconomic Performance and Human Development

Guinea’s GDP growth has been volatile, heavily correlated with commodity prices and political shocks (e.g., the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic, the 2021 coup). While growth rates have often been high on paper (averaging around 5-6% pre-coup), this has not translated into poverty reduction.

-

Poverty and Inequality: Over half the population lives in poverty. Urban-rural disparities are stark, and youth unemployment is endemic.

-

Agriculture: Employing a majority of the workforce but receiving minimal investment, the sector remains subsistence-based and vulnerable to climate change.

-

Infrastructure: Chronic deficits in energy, transportation, and healthcare constrain economic diversification and quality of life. Guinea has immense hydropower potential, yet power outages are routine.

-

Corruption: Pervasive corruption acts as a massive leakage from the public treasury. Guinea consistently ranks poorly on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

4. Regional and International Relations

-

ECOWAS: Guinea’s suspension from the Economic Community of West African States following the 2021 coup has strained relations. The junta’s defiance of transition timelines has led to maintained sanctions and diplomatic isolation, though not the severe economic sanctions applied to neighbors Mali and Niger.

-

International Partners: Relationships are complex. Western partners (the EU, U.S.) call for a swift democratic transition and have imposed targeted sanctions on junta leaders. Meanwhile, China maintains a pragmatic, non-ideological engagement focused solely on resource access and infrastructure-for-minerals deals, providing the junta with a crucial economic and diplomatic lifeline. Russia’s Wagner Group has also sought to expand its influence, offering security assistance in exchange for mining concessions.

-

Neighbors: Stability in Guinea is crucial for a region plagued by jihadist insurgencies. Its role as the “water tower of West Africa,” with the headwaters of the Niger, Senegal, and Gambia rivers, gives it outsized environmental and agricultural influence.

5. Synthesis and Conclusion: Trapped in Transition

Guinea’s status is defined by a persistent and debilitating tension:

-

Political Volatility vs. Economic Potential: Each cycle of hope (Condé’s election, Doumbouya’s anti-corruption rhetoric) is followed by regression towards authoritarianism and instability, scaring away non-extractive investment and undermining long-term planning.

-

Resource Wealth vs. Human Poverty: The mineral sector generates fiscal revenues and export earnings but does so within a system of elite capture, failing to fund the education, healthcare, and infrastructure needed for sustainable development.

-

Sovereign Aspiration vs. Integration Realities: Guinea’s historical defiance continues in the junta’s stance toward ECOWAS, but this sovereignty comes at the cost of regional integration and security cooperation, even as it opens the door to alternative, less democratic international partners.

Prospects: The path forward is fraught. The Simandou project offers a generational opportunity, but its benefits will be squandered without a credible, inclusive, and accountable political settlement. A genuine transition to a rules-based, democratic system—where power is contested fairly, ethnic divisions are managed institutionally, and mineral wealth is governed transparently for the benefit of all citizens—remains the fundamental prerequisite for Guinea to escape its perpetual transition and finally realize its vast potential. Until then, it will remain a cautionary tale of how resource wealth, in the absence of functional governance, can become not an engine of development, but a source of perpetual conflict and stasis.

Sources:

-

African Development Bank. (2023). Guinea Economic Outlook.

-

Campbell, J. (2021). The Coup in Guinea Is a Setback for Democracy. Council on Foreign Relations.

-

McNamee, T. (2023). The Simandou Saga: How Guinea’s iron ore dream is finally taking shape. Mining Weekly.

-

Ministère des Mines et de la Géologie (Guinea). (2023). Rapport Annuel.

-

Transparency International. (2023). Corruption Perceptions Index.

-

U.S. Geological Survey. (2023). Mineral Commodity Summaries: Bauxite and Alumina.

-

World Bank. (2023). The Republic of Guinea: Overview.

-

International Crisis Group. (2022-2024). Reports on Political Transitions in Guinea.

-

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). (2023). Guinea EITI Report.

Related Posts

Political Instability & Democratic Backsliding in Africa

Introduction: The Promise and the Peril The early 1990s marked…

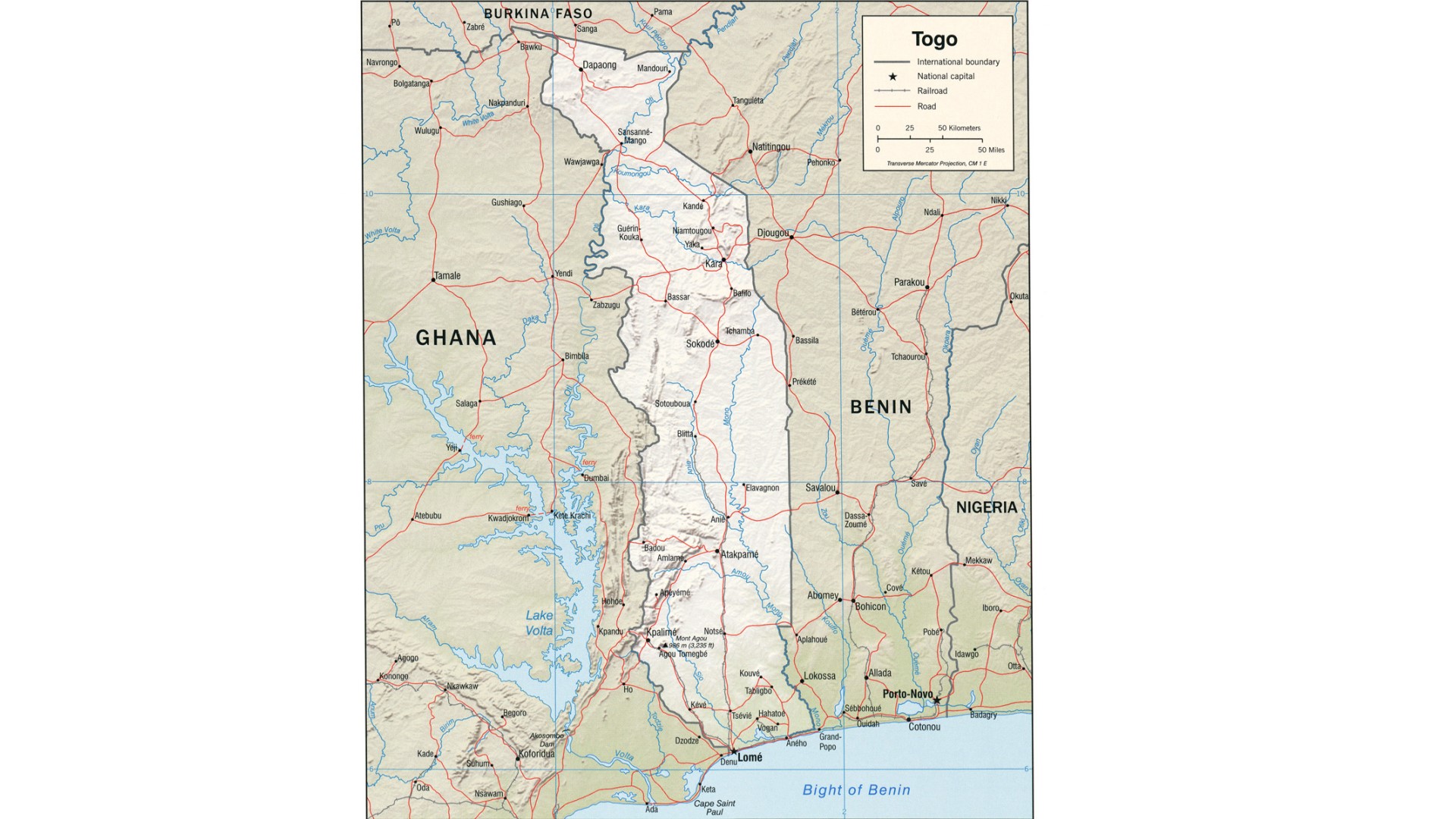

Togo in A Nexus of Stability, Vulnerability, and Dynastic Governance

Abstract: This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the contemporary…

Great Power Competition & Strategic Autonomy in Africa

Introduction: From Pawn to Player in a Multipolar World Africa,…