Abstract

This paper examines Zimbabwe’s contemporary economic and political status, with particular focus on its complex and evolving relationship with the East African Community. It reveals a nation pursuing a strategic paradox: leveraging its position as a regional integration leader within COMESA and the Tripartite Free Trade Area to overcome its exclusion from the EAC, while simultaneously navigating profound domestic tensions between hard-won economic stabilization and democratic backsliding. Economically, Zimbabwe presents a narrative of dramatic turnaround and persistent fragility. After decades of crisis, inflation has fallen below 10% for the first time since 1997, foreign exchange reserves have surpassed $1.2 billion, and the government projects growth of at least 8.5% in 2026—the fastest pace in 14 years . Yet skepticism remains warranted: the IMF projects more modest 5% growth, external debt stands at approximately $22.6 billion, and the structural vulnerabilities of currency dependence and commodity concentration persist . Politically, Zimbabwe faces a critical democratic juncture. The cabinet’s approval of draft legislation to extend presidential terms to seven years and shift to parliamentary selection of the president has ignited fierce domestic and international controversy, with legal experts arguing such changes require a referendum and cannot benefit a sitting president . Regionally, Zimbabwe occupies a distinctive position: a COMESA and SADC member that will assume the COMESA chairmanship in 2026, enabling it to shape the COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite agenda from a leadership position despite not being an EAC member . Its export growth from $4.2 billion in 2021 to $9.7 billion in 2025, coupled with strategic bilateral engagements with Uganda and Egypt, signals a deliberate strategy to deepen ties with East African economies . This paper argues that Zimbabwe’s status embodies the paradox of a state pursuing regional reintegration as a pathway out of pariah status, even as domestic political choices threaten to undermine the credibility on which such reintegration depends.

1. Introduction

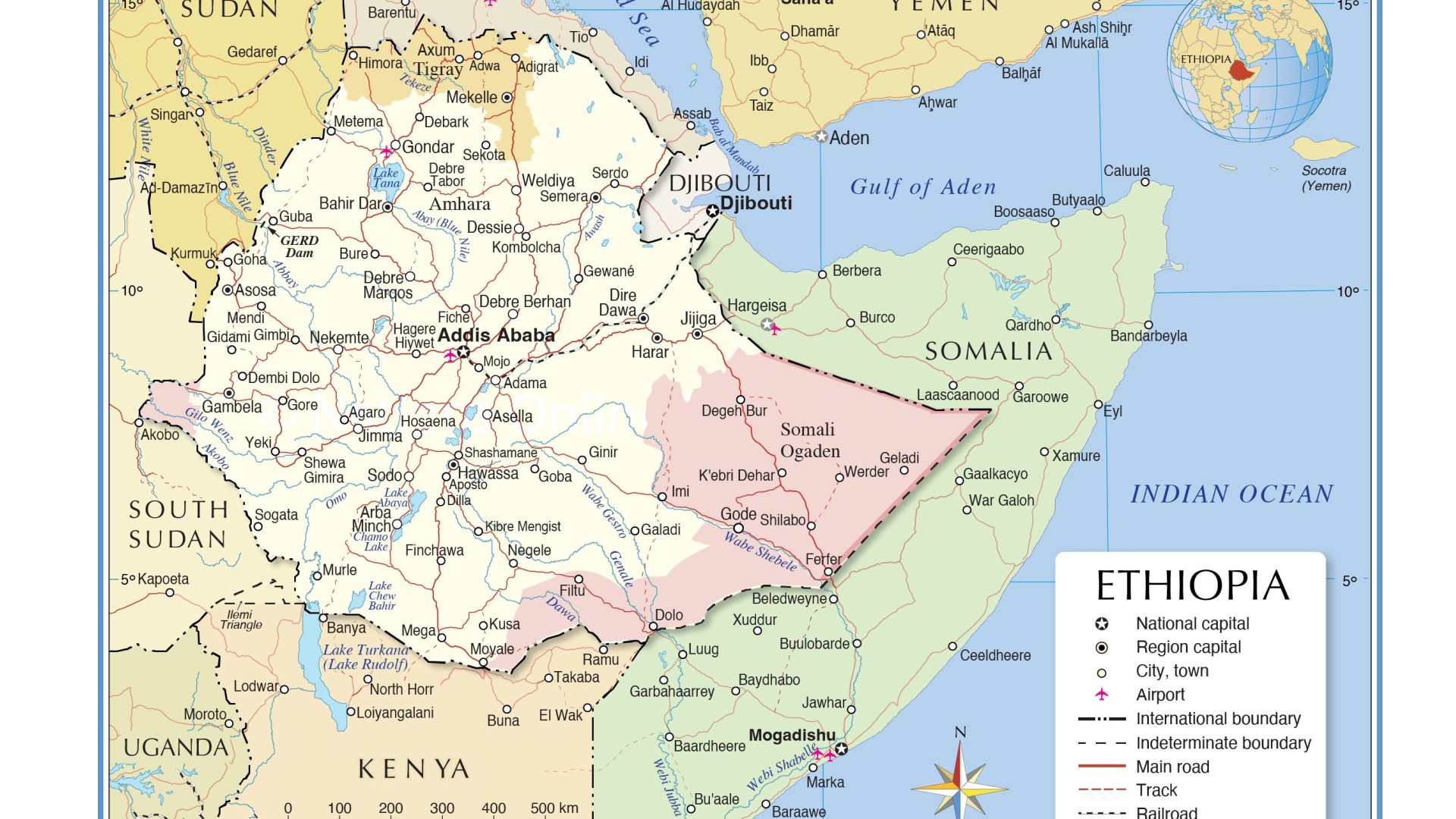

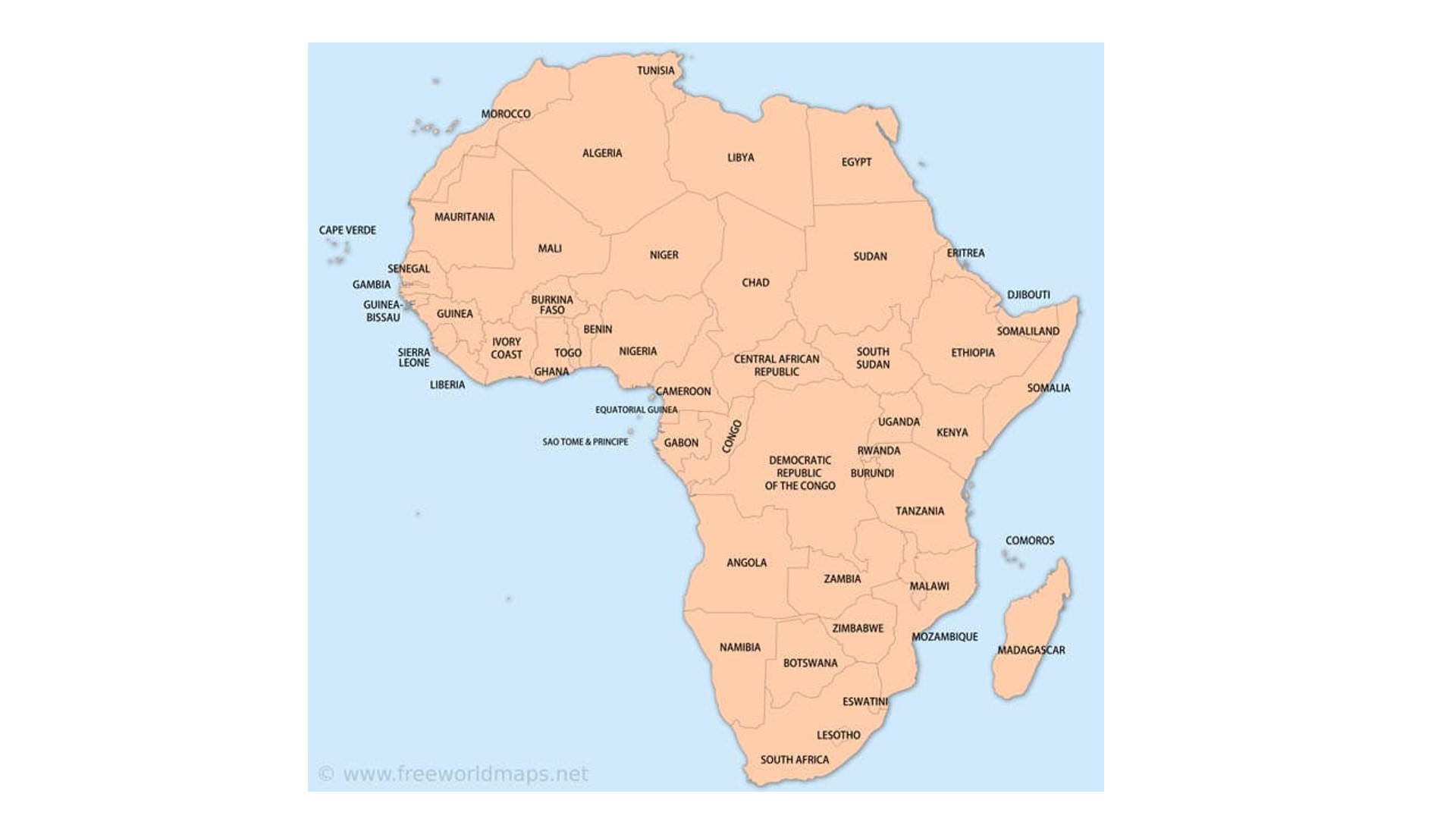

Zimbabwe occupies an anomalous and deeply contested position in the regional architecture of Eastern and Southern Africa. Geographically anchored in the south, it is a founding member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Economically, it is a key participant in the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). Politically, it remains outside the East African Community (EAC), yet its strategic ambitions increasingly reach toward the eastern bloc through infrastructure, trade, and diplomatic engagement.

This positioning reflects both choice and constraint. Zimbabwe’s exclusion from the EAC is not accidental—it reflects fundamental differences in governance trajectories, economic structures, and political alignments. Yet Zimbabwe cannot afford to ignore East Africa. As a landlocked economy dependent on access to global markets, the corridors connecting to Tanzanian ports are vital. As a member of the COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite Free Trade Area, its economic future is intertwined with the seamless movement of goods across eastern and southern Africa. And as a state seeking to overcome decades of international isolation, engagement with the dynamic economies of East Africa offers pathways to diversification and growth.

In early 2026, Zimbabwe presents a study in dramatic contradictions. Economically, the country has achieved what many considered impossible: inflation has fallen below 10% for the first time since 1997, the new Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) currency has stabilized, and foreign exchange reserves have surpassed $1.2 billion . The government projects growth of at least 8.5% in 2026—the fastest pace in 14 years—buoyed by a recently concluded Staff-Monitored Program with the International Monetary Fund . Mining and agriculture are recovering, exports have more than doubled from $4.2 billion in 2021 to $9.7 billion in 2025, and bilateral business forums with Uganda and Egypt signal strategic outreach to eastern markets .

Yet beneath these headline numbers, profound fragilities persist. The IMF projects more modest 5% growth for 2026 . External debt stands at approximately $22.6 billion, with arrears to international financial institutions blocking access to new financing . Skepticism remains deeply ingrained among investors and citizens alike, shaped by decades of policy reversals, currency collapses, and the trauma of 2008 hyperinflation when pensions were wiped out and prices doubled in hours .

Politically, Zimbabwe’s trajectory is even more contested. President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who came to power in 2017 after a military coup ousted Robert Mugabe, is pursuing constitutional amendments that would extend presidential terms to seven years and shift selection of the president from direct popular vote to parliamentary election . Critics argue these changes violate the spirit of the 2013 constitution, which Zimbabweans overwhelmingly approved in a referendum that introduced term limits. Legal experts contend that altering term limits requires a referendum and cannot benefit a sitting president . The government frames the reforms as necessary for political stability and policy continuity .

Regionally, Zimbabwe is poised to assume the COMESA chairmanship in 2026, a major diplomatic milestone that underscores its growing influence in regional economic affairs . This position will enable Zimbabwe to shape the Tripartite Free Trade Area agenda, coordinating with both EAC and SADC partners from a leadership perch. Its hosting of the COMESA summit and its role as home to the Inter-Africa Trade Company—the implementation agency of the African Continental Free Trade Area—position it as a potential “nerve centre of Africa’s trade” .

This paper investigates Zimbabwe’s multifaceted status through four analytical lenses. Section two examines economic stabilization, the IMF program, and structural vulnerabilities. Section three analyzes political dynamics, including constitutional amendments, succession politics, and governance tensions. Section four considers Zimbabwe’s regional positioning—its COMESA leadership, engagement with East African economies, and role in the Tripartite framework. Section five addresses the paradoxes inherent in Zimbabwe’s simultaneous pursuit of economic reform, political consolidation, and regional reintegration.

2. The Economic Dimension: Stabilization, Skepticism, and Structural Fragility

2.1 The Inflation Milestone: Below 10% for the First Time Since 1997

Zimbabwe’s most significant economic achievement in 2026 is the dramatic stabilization of inflation. In January 2026, annual inflation fell to 4.1%, dropping below 10% for the first time since 1997 . This milestone represents a profound departure from decades of currency chaos, when inflation peaked at an estimated 89.7 sextillion percent in November 2008, rendering the Zimbabwe dollar worthless and forcing citizens to barter for basic goods.

The current stabilization reflects multiple factors. Tight monetary policy has curbed the liquidity surges that historically fueled rapid currency depreciation. Fiscal discipline has restrained government spending and borrowing. The introduction of the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) currency, backed by gold and foreign reserves, has created a more credible monetary anchor . Foreign exchange reserves have risen above $1.2 billion, providing a buffer against external shocks .

Improved terms of trade are providing additional support. Lower oil prices have reduced import costs, while surging gold and platinum prices—gold has soared by over 40%—have bolstered export earnings and reserve accumulation . The IMF projects inflation will remain in single digits throughout 2026, “reflecting tight monetary conditions and a more stable foreign-exchange market” .

Yet skepticism remains deeply embedded. The Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce cautions that stabilization is “only the beginning,” warning that “history will judge this moment not by the inflation rate itself, but by whether policymakers protect it long enough for confidence to take root” . This caution reflects bitter experience: previous stabilizations have unraveled amid policy reversals, political pressures, or renewed currency instability.

2.2 Growth Projections: Optimism and Divergence

Zimbabwe’s growth trajectory for 2026 is subject to dramatically different assessments. The government, through Finance Secretary George Guvamatanga, projects growth of at least 8.5%, potentially reaching 9-10%—the fastest annual expansion since 2012 . This forecast is buoyed by the recently concluded Staff-Monitored Program with the IMF, which signals a return to international engagement and reform credibility.

The IMF offers a more conservative projection of approximately 5% growth for 2026, driven by “continued strength in agriculture and mining” . The African Development Bank projects 4% growth in 2026, down from 6% in 2025, owing to inflationary and exchange rate pressures . These divergent forecasts reflect differing assessments of the durability of stabilization and the depth of structural reform.

Sectoral analysis reveals both strengths and vulnerabilities. Agriculture is recovering from the 2024 drought-induced contraction, supported by better rains . Mining is benefiting from high gold prices and recovering platinum and lithium output—the latter critical to global energy-transition supply chains . Services are expanding, though from a constrained base.

However, structural weaknesses persist. Export concentration in minerals leaves the economy exposed to commodity price volatility. Manufacturing capacity remains far below historical levels. Unemployment and informality remain endemic. As the University of Zimbabwe’s Dr. Nyasha Kaseke notes, “Zimbabwe needs to diversify its export markets and reap more trade benefits,” emphasizing “beneficiation as well as utilising comparative advantage” .

2.3 Fiscal Position and External Debt

Zimbabwe’s fiscal position has improved but remains precarious. The African Development Bank reports that the fiscal deficit narrowed to 1.2% in 2024, with projections of further improvement to -0.9% in 2025 and -0.6% in 2026, reflecting fiscal consolidation and stronger revenue mobilization . The Treasury expects revenue of $8 billion in 2025, backed by an aggressive collection campaign.

However, the debt burden casts a long shadow. Treasury recorded debt at $22.6 billion as of June 2025, comprising $13.7 billion external and $8.8 billion domestic . The World Bank projects debt to reach 64.6% of GDP ($33.78 billion) in 2025, declining to 59% ($30.85 billion) in 2026 . The IMF’s estimates are lower, projecting $23.53 billion in 2025 tapering to $21.75 billion in 2026.

The critical constraint is arrears. Zimbabwe has accumulated approximately $13 billion in arrears to the World Bank, African Development Bank, European Investment Bank, and Paris Club countries . These arrears block access to new financing from international financial institutions and constrain the country’s ability to secure new credit lines or attract the foreign investment needed for economic revival. The IMF has conditioned any future financial support on “a comprehensive restructuring of external debt, including clearance of arrears and a compatible reform plan” .

2.4 The ZiG Currency: Credibility Test

The Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) currency represents the latest iteration of efforts to re-establish a local currency in place of the U.S. dollar, which became the dominant medium of exchange after the 2009 abandonment of the Zimbabwe dollar. Backed by gold and foreign reserves, the ZiG has achieved initial stability, contributing to inflation moderation and improved market confidence.

However, the currency’s long-term credibility remains untested. Previous currency experiments—the RTGS dollar, the bond note, various re-denominations—have all failed amid policy inconsistency, fiscal dominance, and loss of confidence. The ZiG’s viability depends on sustained discipline: maintaining tight monetary policy, restraining fiscal deficits, and accumulating reserves sufficient to defend the currency against shocks.

The IMF’s staff-monitored program provides external validation and policy anchor, but involves no immediate financial disbursement . Its success will be measured by whether it paves the way for a financing agreement and, ultimately, arrears clearance and re-engagement with international financial institutions.

2.5 Export Performance and Trade Diversification

One of Zimbabwe’s most notable economic achievements is the dramatic expansion of exports. From over $4.2 billion in 2021, exports grew to $9.7 billion by 2025—more than doubling in four years . This growth reflects both favorable commodity prices and improved market access through trade promotion efforts by ZimTrade, the national trade development organization.

Zimbabwe is now pursuing further export growth through strategic bilateral engagements. In March 2026, the country will host the Zimbabwe–Uganda Business Forum and the Zimbabwe–Egypt Business Forum, aimed at strengthening economic cooperation and increasing bilateral trade . These engagements are anchored in opportunities presented by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and COMESA trading frameworks.

The strategic logic is clear: diversifying export markets reduces dependence on traditional partners and creates pathways for value-added products. As Dr. Kaseke notes, “riding on the current gains, there is a lot that needs to be done to facilitate growth through beneficiation as well as utilising comparative advantage” . This requires moving beyond raw mineral exports to processing and manufacturing that capture greater value and generate employment.

2.6 Business Environment and Investment Climate

Despite macroeconomic improvements, the business environment remains challenging. Local firms have raised concerns over multiple taxes, warning that the fiscal burden threatens their operations . Regulatory unpredictability, governance weaknesses, and corruption continue to deter investment and increase transaction costs.

The government’s ease of doing business reforms, cited by Finance Secretary Guvamatanga as supporting the growth forecast, aim to address these constraints . However, meaningful improvement requires not only policy changes but consistent implementation and institutional strengthening.

For investors, Zimbabwe’s vast mineral resources—including lithium and platinum critical to global energy-transition supply chains—remain attractive. But durable price stability and governance credibility are prerequisites for unlocking sustained investment. As the Moneyweb analysis notes, “durable price stability would ease investor concerns about Zimbabwe’s risk profile and help unlock investment in its vast mineral resources” .

3. The Political Dimension: Constitutional Controversy and Succession Politics

3.1 The 2030 Agenda: Extending Presidential Rule

The central political controversy in early 2026 is the government’s push to extend President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s tenure beyond the 2028 constitutional limit. In February 2026, Zimbabwe’s cabinet approved draft legislation that would amend the constitution to:

-

Extend the presidential term from five to seven years

-

Allow the president to be elected by parliament rather than through direct popular vote

-

Extend parliamentary terms from five to seven years

-

Increase Senate seats from 80 to 90 through 10 presidential appointees

If enacted, these changes would enable Mnangagwa, 83, to remain in office until at least 2030. The government frames the reforms as necessary to “reduce election-related disruptions and enhance policy continuity, political stability and the efficiency of state architecture” .

Justice Minister Ziyambi Ziyambi announced that public consultations would be held before the bill heads to parliament, where both chambers are dominated by the ruling Zanu-PF party . However, legal experts argue that constitutional amendments affecting term limits require a referendum under the 2013 constitution and that such changes cannot benefit a sitting president .

3.2 Historical Context: Term Limits and the 2013 Constitution

The current controversy must be understood against the historical backdrop of Zimbabwe’s constitutional evolution. In 2013, Zimbabweans overwhelmingly approved a new constitution in a referendum—a document that introduced presidential term limits for the first time. At the time, Robert Mugabe’s grip on power seemed entrenched; he had ruled the country since independence in 1980. Term limits were seen as a mechanism to prevent indefinite rule .

The 2013 constitution limits presidents to two five-year terms. Mnangagwa, who first came to power in 2017 after a military coup ousted Mugabe, won elections in 2018 and 2023—though results were disputed by challengers. His second term is due to expire in 2028 .

The slogan “2030 he will still be the leader” began appearing at Zanu-PF rallies two years ago, with supporters arguing Mnangagwa needed to remain in office to complete his “Agenda 2030” development programme. Mnangagwa publicly rejected the idea at the time, but the current legislative push suggests a strategic shift .

3.3 Internal Party Dynamics and the Geza Episode

The succession debate has exposed internal fissures within Zanu-PF. Blessed Geza, a respected veteran of the 1970s war of independence and former member of the party’s powerful central committee, emerged as Mnangagwa’s most vocal critic. Known as “Bombshell,” Geza launched scathing attacks on the president’s ambition to stay in power, apologizing for helping him come into office and accusing him of nepotism .

Zanu-PF expelled Geza for disloyalty, forcing him into hiding. Yet he continued to attract a large following on social media, regularly posting videos calling for protests. Hours before his death in February 2026, a message posted on his social media pages urged Zimbabweans to carry forward the “noble war” to remove President Mnangagwa and “end the plunder of our country” .

Geza’s death—he was in South Africa when his family announced it—has removed a prominent internal critic, but the underlying tensions persist. The Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association’s national chairman, Andrease Ethan Mathibela, eulogized Geza: “At a time when silence would have been easier, he chose to speak out against corruption and nepotism that continue to undermine the promise of independence” .

3.4 Democratic Trajectory and International Response

Zimbabwe’s democratic trajectory under Mnangagwa has been characterized by contested elections, constrained political space, and periodic repression. The 2023 election results were disputed by challengers. Journalists and opponents have faced arbitrary arrest. Civil society space has narrowed.

The constitutional amendment push has intensified international scrutiny. The United States, European Union, and other Western partners have expressed concern, though concrete responses remain limited. The IMF’s staff-monitored program, while focused on economic reforms, implicitly conditions future engagement on governance improvements.

Critics argue that the amendments, if enacted, would represent a fundamental breach of the democratic bargain embodied in the 2013 constitution. By shifting presidential selection from popular vote to parliamentary election, they would insulate the executive from direct accountability to citizens. By extending terms midstream, they would violate the principle that rules should not be changed to benefit incumbents.

Government spokespersons reject these criticisms, framing the reforms as strengthening governance. Information Minister Jenfan Muswere stated that the objective is “to reduce election-related disruptions and enhance policy continuity, political stability and the efficiency of state architecture” .

3.5 Succession and the “Crocodile’s” Future

Mnangagwa, nicknamed “the crocodile” for his political cunning, has navigated Zimbabwe’s treacherous political landscape for decades. As Mugabe’s deputy, he fell out with the then-president over the growing political ambitions of the first lady, survived purges, and ultimately returned to power through military intervention .

His current gambit—seeking to extend his rule through constitutional amendment—reflects both personal ambition and institutional logic. Zanu-PF has governed Zimbabwe since independence in 1980, and party elites have vested interests in continuity. Yet the succession question cannot be indefinitely deferred. At 83, Mnangagwa’s eventual departure is inevitable, and the absence of clear succession mechanisms creates uncertainty.

The internal party wrangles over who will eventually succeed him remain unresolved. The Geza episode revealed significant discontent, and while his death has silenced a prominent voice, the underlying factions and ambitions persist.

4. Regional Positioning: COMESA Leadership and East African Engagement

4.1 COMESA Chairmanship: A Regional Platform

Zimbabwe’s assumption of the COMESA chairmanship in 2026 represents a significant diplomatic milestone and a platform for advancing its regional integration agenda. President Mnangagwa was elected incoming chairperson at the COMESA summit in Nairobi, Kenya, in October 2025, with Zimbabwe set to host the 25th COMESA Heads of State and Government Summit later in 2026 .

The chairmanship carries both symbolic and substantive weight. Symbolically, it signals Zimbabwe’s return to regional leadership after years of isolation and reputational damage. Substantively, it enables Zimbabwe to shape the COMESA agenda, prioritize initiatives aligned with its interests, and convene regional partners around shared objectives.

Foreign Affairs Minister Amon Murwira articulated Zimbabwe’s priorities: “We are looking to deepen regional integration, under the Africa Continental Free Trade Area, and as you know, Zimbabwe won the bid to host the Inter-Africa Trade Company, which is the implementation agency of the Africa Continental free trade area. And we are looking forward to become the nerve centre of Africa’s trade” .

4.2 The Tripartite Framework: COMESA-EAC-SADC Integration

Zimbabwe’s COMESA leadership coincides with critical developments in the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA), which brings together COMESA, EAC, and SADC. In 2026, COMESA will oversee the validation and adoption of the Tripartite Simplified Trade Regime (TSTR), a new framework to streamline cross-border trade for small-scale traders across the three blocs .

For Zimbabwe, the Tripartite framework offers pathways to integrate with East African economies without formal EAC membership. By harmonizing rules, reducing barriers, and facilitating trade across the three blocs, the TFTA creates a seamless market spanning from the Red Sea to the Cape. Zimbabwe’s role as COMESA chair positions it to influence this process and ensure its interests are reflected.

The strategic logic is clear: if Zimbabwe cannot join the EAC, it can help shape the rules governing trade between the EAC and its neighbors. Leadership in COMESA provides leverage that bilateral engagement alone cannot achieve.

4.3 East African Engagement: Uganda, Egypt, and Beyond

Zimbabwe is pursuing direct bilateral engagement with key East African economies to complement its multilateral leadership. In March 2026, the country will host the Zimbabwe–Uganda Business Forum and the Zimbabwe–Egypt Business Forum, organized by ZimTrade .

These forums are designed to strengthen economic cooperation and increase bilateral trade, anchored in opportunities presented by COMESA and AfCFTA frameworks. Uganda represents a growing East African market with complementarities in agriculture, manufacturing, and services. Egypt offers access to North African markets and potential investment in infrastructure and industry.

The choice of partners is strategic. Uganda is a dynamic EAC economy with expanding trade ties across the region. Egypt, while not an EAC member, is a COMESA heavyweight and a gateway to Middle Eastern and Mediterranean markets. Engaging both diversifies Zimbabwe’s trade relationships and builds constituencies for deeper integration.

4.4 Export Growth and Market Diversification

Zimbabwe’s export growth from $4.2 billion in 2021 to $9.7 billion in 2025 provides the economic foundation for its regional engagement . This growth demonstrates that Zimbabwean producers can compete in regional markets when conditions permit and that trade promotion efforts can yield results.

The challenge is to sustain and diversify this growth. Continued dependence on mineral exports—particularly gold, platinum, and lithium—leaves the economy exposed to price volatility. Expanding agricultural exports, processed goods, and services requires investment, policy support, and market access.

ZimTrade’s strategy of targeted bilateral engagements reflects recognition that diversification requires deliberate effort. By identifying specific opportunities in specific markets and facilitating business-to-business connections, trade promotion organizations can accelerate export growth.

4.5 Infrastructure Corridors and Connectivity

Beyond trade agreements, Zimbabwe’s connection to East Africa depends on physical infrastructure. The corridors linking Zimbabwe to Tanzanian ports—particularly Dar es Salaam through the TAZARA railway—are vital for landlocked Zimbabwe’s access to global markets. Rehabilitation of this railway, with support from development partners, is essential for reducing transport costs and improving export competitiveness.

Zimbabwe also participates in broader regional infrastructure initiatives, including those under COMESA, SADC, and the Tripartite framework. The North-South Corridor, which runs from Dar es Salaam through Zimbabwe to South Africa, is a priority for regional integration and a focus of development partner investment.

4.6 The EAC Question: Membership or Partnership?

Zimbabwe is not an EAC member, and formal membership appears unlikely in the foreseeable future. The barriers are multiple: geographic distance, different institutional memberships (SADC remains Zimbabwe’s primary political home), governance concerns, and the absence of a compelling political driver for accession.

Yet Zimbabwe’s relationship with the EAC is deepening through multiple channels. The Tripartite framework creates institutional linkages. Bilateral trade and investment flows are growing. Infrastructure corridors connect Zimbabwe to EAC ports. And Zimbabwe’s COMESA leadership provides a platform for engagement with EAC partners.

This suggests that “strategic partnership” rather than “membership” will characterize Zimbabwe-EAC relations for the medium term. Zimbabwe can benefit from East African integration without formal accession, leveraging its position in overlapping regional formations to access markets and build relationships.

5. The Paradox of Simultaneous Reform and Retrenchment

5.1 Economic Stabilization vs. Democratic Backsliding

Zimbabwe’s current trajectory reveals a fundamental tension between economic stabilization and democratic backsliding. The same government that has achieved inflation below 10%, stabilized the currency, and secured an IMF program is simultaneously pursuing constitutional amendments that critics argue undermine democratic institutions.

This tension carries material consequences. International partners, including the IMF, condition deeper engagement on governance improvements. Investors assess political risk alongside economic fundamentals. The credibility that enables access to capital and markets depends on both policy consistency and institutional legitimacy.

The government appears to calculate that economic performance will outweigh governance concerns in both domestic political calculations and international partner assessments. The IMF’s staff-monitored program, while focused on economic reforms, proceeds despite governance criticisms. Investors continue to explore opportunities in mining and other sectors. Regional partners engage through COMESA and bilateral channels.

Whether this calculus proves sustainable depends on the severity of democratic backsliding, the responsiveness of international actors, and the ability of opposition and civil society to mobilize pressure. If the constitutional amendments proceed without meaningful consultation or popular legitimacy, the reputational damage could offset economic gains.

5.2 Regional Integration vs. Domestic Consolidation

Zimbabwe’s simultaneous pursuit of regional integration leadership and domestic political consolidation creates another tension. The COMESA chairmanship requires Zimbabwe to project stability, predictability, and commitment to regional norms. Domestic constitutional controversy undercuts that projection.

Regional partners may tolerate governance differences—many EAC and SADC members have their own democratic deficits—but extreme or destabilizing moves can generate pushback. The Tripartite framework and AfCFTA implementation require trust and coordination; actions that signal unreliability or unilateralism can undermine cooperation.

Zimbabwe’s ability to navigate this tension depends on diplomatic skill and the responsiveness of regional institutions. COMESA leadership provides a platform, but also scrutiny. Bilateral partnerships offer flexibility, but also expose Zimbabwe to partner concerns.

5.3 The Credibility Gap: Words vs. Actions

The central challenge for Zimbabwe is bridging the credibility gap between official pronouncements and on-the-ground realities. The government projects confidence—8.5% growth, stable inflation, export expansion—but skepticism remains deeply embedded among citizens, investors, and international partners.

This skepticism is rooted in experience. As the Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce noted, “History will judge this moment not by the inflation rate itself, but by whether policymakers protect it long enough for confidence to take root” . The same applies to governance: constitutional promises matter less than whether institutions function impartially, whether elections are credible, and whether citizens can express dissent without fear.

Bridging this gap requires sustained performance over time, not isolated achievements. It requires policy consistency that outlasts political cycles. It requires institutional strengthening that constrains arbitrary power. And it requires demonstrated commitment to the rules and norms that underpin both economic and political credibility.

5.4 The Geopolitical Dimension: Navigating Between Powers

Zimbabwe’s regional positioning occurs within a broader geopolitical context. The country maintains close ties with China, which has invested significantly in mining and infrastructure. It engages with Russia and other non-Western powers. It seeks to rebuild relationships with Western partners while resisting pressure for political liberalization.

This balancing act carries both opportunities and risks. Diversified partnerships reduce dependence on any single actor and create options for financing and investment. But they also complicate alignment with international norms and can generate tensions with traditional partners.

For East Africa, Zimbabwe’s geopolitical positioning matters less than its practical contributions to regional integration. As COMESA chair, Zimbabwe’s effectiveness will be judged by its ability to advance the Tripartite agenda, facilitate trade, and strengthen regional institutions—not by its alignment in great power competition.

6. Conclusion: The Pariah’s Gambit

Zimbabwe’s economic and political status in relation to East Africa reflects a strategic gambit by a state seeking to overcome decades of isolation through regional integration leadership, even as domestic political choices threaten the credibility on which such leadership depends. Economically, the country has achieved remarkable stabilization—inflation below 10% for the first time since 1997, reserves above $1.2 billion, exports more than doubled to $9.7 billion—yet structural vulnerabilities persist in debt, currency credibility, and commodity dependence . Politically, Zimbabwe faces a critical juncture as constitutional amendments to extend presidential rule ignite domestic controversy and international concern . Regionally, Zimbabwe’s assumption of the COMESA chairmanship in 2026 positions it to shape the Tripartite Free Trade Area agenda and deepen engagement with East African economies through bilateral partnerships with Uganda, Egypt, and others .

Several conclusions emerge for understanding Zimbabwe’s status in relation to East Africa:

First, Zimbabwe matters to East Africa as a COMESA partner and corridor state. Its leadership of the Tripartite Simplified Trade Regime development will directly affect small-scale traders operating between EAC and COMESA markets. Its infrastructure connections to Tanzanian ports are vital for regional trade. Its export growth creates opportunities for complementary exchange.

Second, Zimbabwe’s economic stabilization offers lessons and cautions for East African partners. The IMF program demonstrates pathways to re-engagement, but the arrears overhang and debt challenges illustrate the costs of prolonged crisis. The inflation milestone shows what disciplined policy can achieve, but skepticism about durability warns that gains must be protected.

Third, Zimbabwe’s political trajectory echoes governance debates across East Africa. Constitutional amendments, term limit controversies, and succession politics resonate in a region where several countries face similar questions. How Zimbabwe navigates these tensions will inform regional discussions about democratic resilience and institutional integrity.

Fourth, Zimbabwe’s positioning between eastern and southern orientations illustrates the complexity of overlapping regional memberships. As COMESA chair, Zimbabwe can help harmonize frameworks across the Tripartite space, reducing fragmentation and facilitating trade. But this requires credibility and consistent engagement that domestic turbulence could undermine.

The path forward requires managing the paradoxes inherent in simultaneous reform and retrenchment. Economic stabilization must be sustained long enough for confidence to take root. Political institutions must accommodate debate while maintaining stability. Regional leadership must be exercised with sufficient credibility to inspire cooperation rather than skepticism.

For East Africa, Zimbabwe represents a strategic partner whose trajectory matters for the broader integration project. The COMESA chairmanship offers opportunities to advance the Tripartite agenda, deepen trade ties, and build infrastructure connections. But the domestic choices made in Harare will inevitably shape the credibility and effectiveness of regional engagement.

The pariah’s gambit—using regional integration as a pathway out of isolation—is inherently risky. It requires demonstrating that domestic choices align with regional norms and that commitments made at summits translate into action at home. Zimbabwe has opened a window of opportunity through economic stabilization and diplomatic engagement. Whether it can sustain momentum long enough for credibility to take root remains the central question—for Zimbabwe, for its East African partners, and for the future of regional integration across eastern and southern Africa.

References

-

African Development Bank. (2026, February 13). Inflationary pressures threaten Zim growth. NewsDay Zimbabwe.

-

BBC News. (2026, February 9). Bid launched to extend Zimbabwe president’s term in office.

-

ZBC NEWS. (2026, February 8). COMESA summit heads to Zimbabwe as country assumes bloc leadership.

-

Bloomberg. (2026, February 10). Zimbabwe Forecasts Fastest Growth in 14 Years After IMF Deal.

-

Moneyweb. (2026, February 16). Zimbabwe tames inflation, now the test is keeping it below 10%.

-

Bernama. (2026, February 11). Zimbabwe’s Cabinet Backs Bill To Extend President Mnangagwa’s Rule Until 2030.

-

ZBC NEWS. (2026, February 17). Zimbabwe to chair COMESA as exports jump from US$4.2bn to US$9.7bn.

-

ZBC NEWS. (2025, October 8). Zimbabwe to chair COMESA in 2026 as President Mnangagwa takes leadership role.

-

Xinhua. (2026, February 6). IMF projects Zimbabwe’s economy to grow by 5 pct in 2026.

-

Ecofin Agency. (2026, February 13). Zimbabwe Raises 2026 Growth Forecast to 8.5%, Its Fastest Pace in 14 Years.