Abstract

This paper examines Rwanda’s contemporary economic and political status within the East African Community, revealing a nation of profound contradictions. Economically, Rwanda has emerged as one of Africa’s most consistent high-growth performers, with GDP expansion averaging 8.7 percent in 2025, accompanied by currency stabilization and financial sector strengthening. Yet this economic success coexists with persistent inflationary pressures and a widening trade deficit. Politically, Rwanda presents an even more complex picture: domestically stable with efficient institutions and a visionary development agenda, while regionally assertive to the point of military confrontation with neighbors. The country’s support for M23 rebels in the Democratic Republic of Congo has created the most severe crisis in East Africa since the community’s revival, pitting Rwanda against regional partners and exposing fundamental tensions between its “smart power” projection and the cooperative principles underpinning regional integration. This paper argues that Rwanda’s dual status—as both a model of developmental governance and a source of regional destabilization—reflects a strategic choice to prioritize national security and resource interests over multilateral processes, with profound implications for the future of East African integration.

1. Introduction

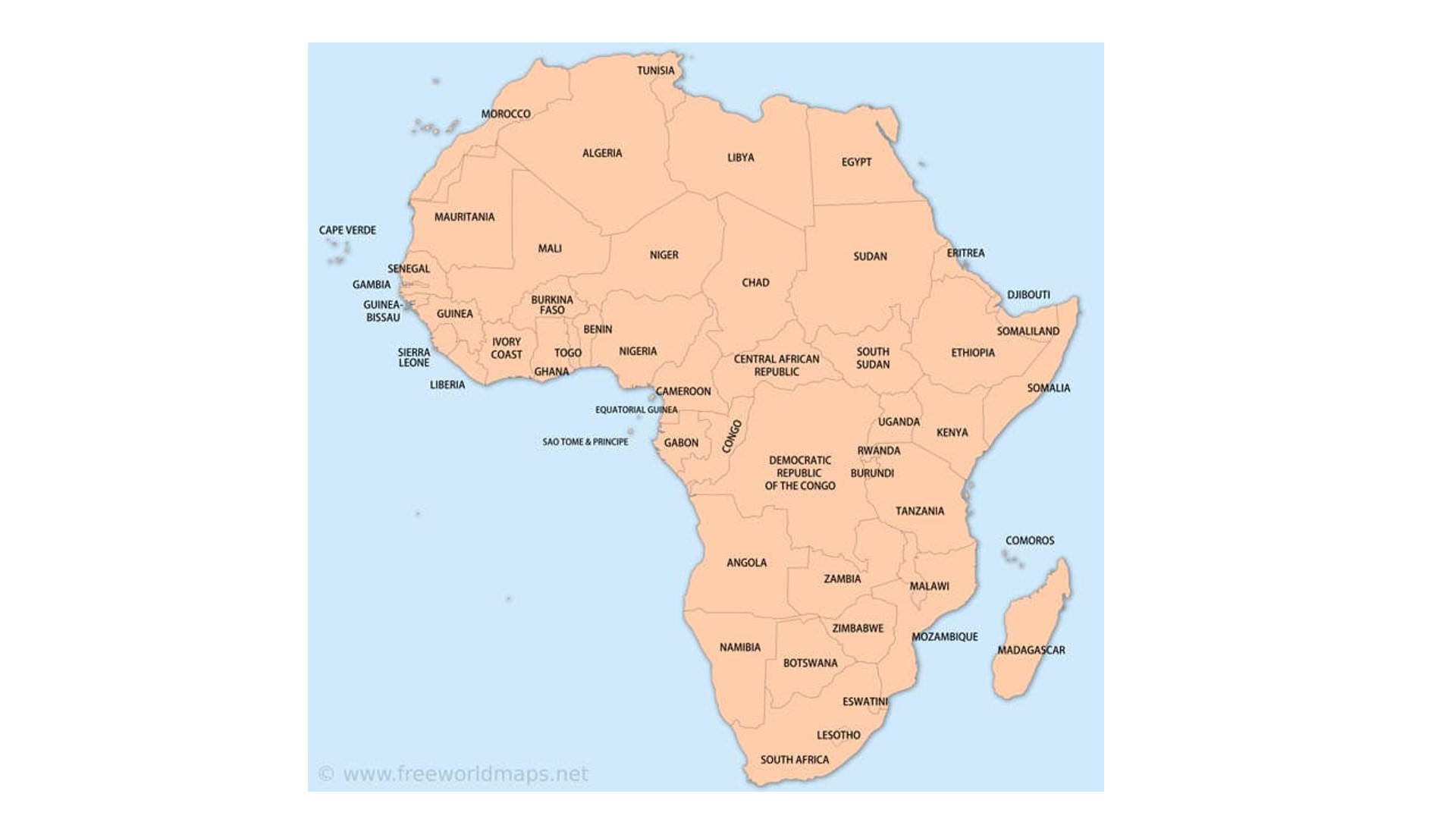

Rwanda occupies an unusual position in East Africa. Twenty-five years removed from the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, the country has engineered one of the most remarkable transformations in modern African history. Its capital, Kigali, stands as a symbol of order and progress in a region often characterized by infrastructural deficits and institutional weaknesses. International financial institutions routinely praise its economic management, and foreign investors increasingly view it as a preferred entry point into African markets.

Yet this narrative of successful post-conflict reconstruction sits uneasily alongside another reality. In early 2026, Rwandan-backed M23 rebels control territory equivalent to some European countries in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. United Nations experts estimate that 4,000 Rwandan Defence Force troops operate across the border. The East African Community, of which Rwanda is a member, finds itself unable to resolve the resulting crisis, with President Paul Kagame publicly questioning whether the regional bloc “exists, and exists for what” .

This paper investigates this paradox. Drawing on recent economic data, policy statements, diplomatic records, and security analysis, it assesses Rwanda’s dual status in East Africa: as an economic outlier whose growth model merits careful study, and as a political actor whose regional ambitions increasingly collide with the cooperative framework of East African integration. The analysis proceeds in three parts. Section two examines Rwanda’s economic performance, macroeconomic management, and structural position within East Africa. Section three analyzes its political and security role, including the DRC crisis and its implications for regional governance. Section four considers the tensions between these dimensions and their implications for Rwanda’s future trajectory and that of the East African Community as a whole.

2. The Economic Dimension: Growth, Stability, and Structural Challenges

2.1 Macroeconomic Performance and Monetary Policy

Rwanda’s economy continues to outperform most regional peers by a substantial margin. During the first three quarters of 2025, economic activity expanded at an average annual rate of 8.7 percent, exceeding the 7.2 percent growth recorded in 2024 . This growth trajectory places Rwanda among the fastest-growing economies not only in East Africa but on the continent as a whole. The Composite Index of Economic Activity increased by 17.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2025, signaling sustained strength in aggregate demand .

This robust performance occurs against a backdrop of subdued global economic conditions. While the world economy grew at a moderate 3.3 percent in 2025 and 2026—below the pre-2020 average of 3.7 percent—Rwanda’s domestic momentum has proven resilient to external headwinds . The finance ministry projects annual expansion will remain above 7 percent through 2028 , suggesting confidence that current growth rates are sustainable.

However, strong growth has been accompanied by mounting price pressures. Headline inflation rose to 7.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2025 and accelerated further to 8.9 percent in January 2026, exceeding the central bank’s target band of 2-8 percent . This inflationary surge reflects multiple factors: higher core inflation in housing, restaurants, and hotels; increased electricity tariffs implemented in October 2025; rising charcoal and fuel prices; and supply constraints for fresh food following below-normal rainfall that affected agricultural output .

In response, the National Bank of Rwanda has adopted a contractionary monetary stance that sets it apart from much of the continent. On February 18, 2026, the Monetary Policy Committee increased the Central Bank Rate by 50 basis points to 7.25 percent—the highest level since August 2023 and the second increase since the bank resumed rate hikes in 2025 . This decision contrasts sharply with the monetary easing underway in Kenya, Egypt, Angola, Ghana, Mozambique, and Zambia, and with the hold positions maintained by Uganda, South Africa, and Tanzania .

Governor Soraya Hakuziyaremye framed the increase as a measured step to contain second-round effects of recent price increases and support inflation’s timely return to the target band . The central bank projects that inflation will remain slightly above 8 percent in the first half of 2026 before gradually easing toward the target range by year-end, assuming improved domestic food supply and moderating global inflation .

2.2 External Sector Developments

Rwanda’s external position presents a mixed picture. Merchandise exports increased by 14.1 percent in 2025, driven by strong performance in traditional exports—coffee and minerals benefited from both higher volumes and favorable global prices—and notable growth in non-traditional exports, particularly processed cooking oil and wheat flour . This export growth demonstrates successful diversification beyond primary commodities and suggests that Rwanda’s manufacturing sector is gaining competitiveness.

However, merchandise imports grew by 6.9 percent, reflecting sustained domestic demand for essential food items, construction materials, and capital goods including computers . Because the absolute increase in import values exceeded the gain in export earnings, Rwanda’s external trade deficit widened by 2.7 percent in 2025 compared to 2024 . This persistent deficit highlights a structural vulnerability: Rwanda’s growth model, heavily dependent on imported inputs and investment goods, generates foreign exchange requirements that exports cannot yet fully meet.

Currency markets showed signs of stabilization in 2025. The Rwandan franc depreciated by 4.4 percent against the U.S. dollar, a marked improvement from the 9.42 percent depreciation recorded in 2024 . This deceleration reflects improved external sector conditions—stronger tourism receipts and increased remittance inflows helped ease foreign exchange pressures—alongside domestic foreign exchange market reforms and the relatively weaker U.S. dollar in global markets .

2.3 Financial Sector Development

Rwanda’s financial sector continues to deepen and strengthen. Total financial sector assets grew 23.7 percent to reach 15.9 trillion Rwandan francs (approximately $10.9 billion) by the end of 2025 . Credit to the private sector expanded across manufacturing, construction, and trade, indicating that financial intermediation is supporting productive investment.

Asset quality remains sound, with non-performing loans at 2.5 percent—comfortably below the regulatory benchmark . The central bank’s Financial Stability Committee assesses that the sector remains strong, supported by adequate capital and liquidity buffers that position institutions to absorb shocks while continuing to support economic growth .

Interest rate dynamics present a more complex picture. The interbank rate increased to 6.87 percent in the fourth quarter of 2025, reflecting the policy rate increase and relatively tight liquidity conditions . However, deposit rates declined sharply—by 152 basis points to 3.98 percent—while lending rates eased only slightly by 13 basis points to 15.72 percent . This divergence suggests that monetary policy transmission remains imperfect, with banks protecting margins by compressing deposit rates more than lending rates.

2.4 Structural Transformation Agenda

Rwanda’s economic strategy is articulated through the Second National Strategy for Transformation, which Prime Minister Justin Nsengiyumva reviewed at the February 2026 National Dialogue Council. The strategy identifies productivity as a key priority, acknowledging persistent gaps in both agriculture and industry . The government is strengthening collaboration with the private sector to address these gaps, recognizing that sustained growth requires moving beyond factor accumulation to genuine productivity gains.

President Kagame’s opening address to the National Dialogue Council emphasized that while Rwanda has made measurable progress, it “must take a bigger step forward” to meet long-term ambitions . He stressed accountability in public service and self-reliance as central pillars of development strategy, urging citizens to take collective responsibility for the country’s future . This emphasis on self-reliance carries both economic and political significance: economically, it signals recognition that external assistance cannot substitute for domestic resource mobilization; politically, it reinforces the ruling party’s narrative of national renewal through collective effort.

3. The Political Dimension: Governance, Regional Power, and the DRC Crisis

3.1 Domestic Governance and Political Continuity

Rwanda’s domestic political landscape is characterized by stability and continuity under President Paul Kagame, who has led the country since 2000. In February 2026, the cabinet approved a constitutional amendment proposed by Kagame to harmonize parliamentary and presidential election calendars . If implemented, this change would allow simultaneous elections, reducing administrative costs—the stated rationale—while potentially reinforcing presidential coattail effects on parliamentary races.

This would not be Rwanda’s first constitutional adjustment affecting electoral timelines. The constitution was last amended in 2015 to allow Kagame to extend his rule through a seven-year term commencing in 2017, followed by two further five-year terms . The current proposal, while less consequential for presidential term limits, continues a pattern of constitutional adaptation to perceived governance requirements.

The February 2026 National Dialogue Council, or Umushyikirano, gathered members of Cabinet and Parliament, private sector representatives, the diplomatic community, local government leaders, and Rwandans from home and abroad . The event’s scope reflects the ruling party’s commitment to participatory governance mechanisms that simultaneously build consensus and reinforce political cohesion. Discussions focused on transformation agenda, economic progress, governance, and citizen engagement—themes that resonate with both domestic audiences and international partners who view Rwanda as a model of effective development governance.

3.2 Regional Diplomatic Engagement

Beyond its borders, Rwanda projects influence through multiple channels. In January 2026, Rwandan diplomat Edda Mukabagwiza was appointed to lead the East African Community’s Election Observation Mission for Uganda’s general elections . The mission comprised 61 observers drawn from EAC Partner States and the Secretariat, reflecting the Community’s commitment to inclusivity and regional representation. Mukabagwiza’s background—former Speaker of Parliament and minister in various portfolios—illustrates how Rwanda deploys experienced officials in regional roles, enhancing its diplomatic footprint.

At the mission’s flag-off, Mukabagwiza emphasized that observers would assess the electoral process independently and objectively, “in accordance with the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community, the EAC Election Observation Principles, the laws of the Republic of Uganda and applicable AU and international standards” . This framing aligns Rwanda with regional norms and international best practices, reinforcing its image as a responsible stakeholder in democratic governance.

3.3 The DRC Crisis: Rwanda’s Regional Challenge

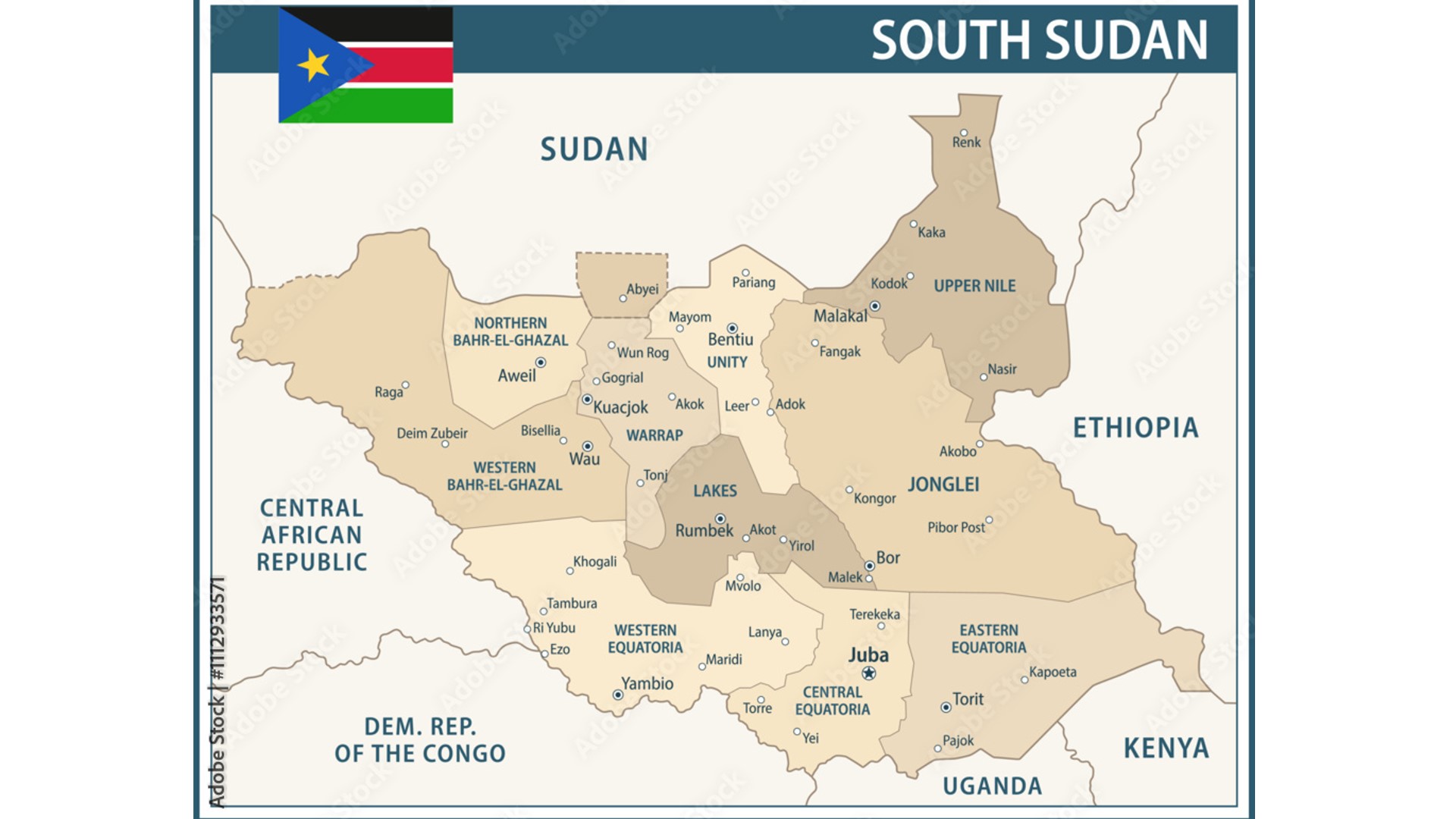

These diplomatic engagements occur against the backdrop of Rwanda’s most significant regional challenge: its military involvement in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Since late 2025, the M23 rebel group—widely acknowledged to receive substantial support from Kigali—has made dramatic territorial gains, including the seizure of Goma, capital of North Kivu province, in January 2026 . Recent UN estimates suggest M23’s 6,000-strong force is supported by approximately 4,000 Rwandan Defence Force troops .

Analysis from the Institute for Security Studies characterizes Rwanda’s approach as “smart power”—combining hard and soft power with targeted diplomatic and economic projection beyond its immediate neighborhood . Rwanda has demonstrated capacity to translate tactical victories into political leverage while managing international criticism through sophisticated diplomacy. This approach is supported by the country’s national brand as peaceful and efficiently run, cultivated through investments in public diplomacy, UN peacekeeping operations, and reliable international partnerships .

However, the same analysis concludes that Rwanda has failed to translate military supremacy into a regional peace plan. The Great Lakes region is characterized by an asymmetric, Rwanda-dominated military order rather than a shared, comprehensive peace framework . The DRC is weakened, internally fragmented, and resentful of Rwanda’s hostile presence. Burundi is militarily bruised and economically strained. Uganda appears more concerned about preventing Kigali from further extending its influence into Congolese territory and upsetting Kampala’s regional ambitions .

3.4 Kagame’s Critique of Regional Institutions

President Kagame’s remarks at the February 2026 Extraordinary Summit of EAC Heads of State revealed deep frustration with regional processes. Speaking as M23 advanced and DRC President Félix Tshisekedi declined to attend, Kagame questioned whether any leader failed to foresee the crisis: “Is there anybody among us who did not see this coming? I for one I saw it coming” .

More fundamentally, Kagame challenged the relevance of the East African Community itself: “Where is the EAC or does it exist? And exists for what? As the East African Community, what did we want from the beginning? What did we do about that? What are we doing now? And what do we want to do for where we want to go?” . He suggested that Arusha processes had become “a talking shop” where participants eloquently define problems but fail to match words with action .

The Rwandan leader specifically criticized the proliferation of peace processes—the Nairobi Process led by Kenya and the Luanda Process led by Angola—arguing that the processes themselves had become ends, and the individuals leading them more important than results . He noted the irony of discussing the DRC crisis without DRC participation: “By the way, the person we are talking about or the country we’re talking about is not represented as we’re discussing. And the country is supposed to be part of East Africa” .

Kagame also addressed the failure of the EAC regional force, which he claimed had shown progress until Tshisekedi “decided they were not doing what he wanted, and went to SADC”—the Southern African Development Community—and “sent everybody else parking” . Rwanda complied with that decision, but the result, in Kagame’s view, was predictable: SADC forces now fight alongside the FDLR (Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda), an armed group founded by perpetrators of the 1994 genocide whom Kagame described as “murderers of our people” .

3.5 International Response and Strategic Calculations

The international response to Rwanda’s DRC involvement has been notably muted. After the UN Group of Experts documented extensive RDF support to M23 in December 2025, no country on the UN Security Council—including the permanent five—called for actions against Kigali . Following the January escalation, the United States, France, Britain, and China directly called for withdrawal of Rwandan forces, but threats to cut aid or impose targeted sanctions have not materialized .

The European Union struggles to form a unified response. While Belgium, Germany, and Sweden advocate more aggressive stances, other European capitals including Lisbon and Paris prefer caution . The EU has various potential leverage points—reviewing European financial support for 4,000 Rwandan security personnel deployed in Mozambique, or re-evaluating aid and supply chain agreements—but has not yet deployed them.

This weak international response reflects Rwanda’s successful cultivation of an image as a stable, business-friendly environment with strong public sector management, anti-corruption measures, and policy consistency . Rwandan troops are among the most deployed on the continent within multilateral peacekeeping missions and bilateral arrangements, further extending the country’s sphere of influence and creating constituencies reluctant to criticize Kigali .

The Institute for Security Studies analysis suggests Rwanda’s assertive stance may serve multiple purposes. Access to Congolese resources could help finance the security and defense apparatus while giving the regime fiscal space to manage social pressures from a rapidly growing and youthful population . Additionally, maintaining confrontation with the DRC may help sustain a “war ethos” among younger generations as the liberation war generation gradually retires, reinforcing discipline and loyalty through collective solidarity amid perceived external threats .

4. The Tension Between Economic Success and Regional Instability

4.1 Divergent Trajectories

The juxtaposition of Rwanda’s domestic economic success with its regional security assertiveness reveals fundamental tensions. Economically, Rwanda presents itself as a model of good governance, attracting foreign investment and international partnerships. Politically, it acts as a revisionist power, challenging post-colonial borders and regional norms. These are not separate dimensions but interconnected aspects of a coherent strategy.

Rwanda’s military dominance enables continued access to Congolese resources, which may help finance domestic development priorities. The country’s efficient public sector management and anti-corruption measures—widely praised by international partners—generate the fiscal space and institutional capacity that support military capabilities. And Rwanda’s contributions to peacekeeping in Mozambique and the Central African Republic burnish its international reputation, creating diplomatic cover for operations less favorably viewed.

4.2 Implications for East African Integration

This strategy carries significant implications for East African integration. The EAC was revived in the 2000s on the premise that shared economic interests would gradually build trust and cooperation, eventually enabling deeper political integration. Rwanda’s behavior suggests that economic interdependence does not automatically moderate security competition. Despite EAC membership, Rwanda has pursued unilateral military solutions to perceived security threats.

The crisis has created new regional alignments. South Africa, whose forces serve in the SADC mission in eastern DRC, has found itself in direct confrontation with Rwanda. President Ramaphosa warned of possible retaliation when M23 shelled positions occupied by South African soldiers, who suffered 13 fatalities . Kagame responded defiantly, questioning how South Africa could threaten Rwanda while fighting alongside FDLR “murderers” .

The DRC’s absence from EAC discussions on its own crisis—a point Kagame emphasized—underscores the community’s limitations when a member state refuses to participate in collective problem-solving. If the EAC cannot address a crisis involving two members (Rwanda and DRC) and affecting several others (Burundi, Uganda, Tanzania), its relevance to regional security is legitimately questionable.

4.3 Sustainability Questions

Whether Rwanda’s current posture is sustainable remains uncertain. The country lacks the economic weight to impose hegemonic leadership across the Great Lakes region . Its GDP, while growing impressively, remains small relative to neighbors. Continued confrontation carries reputational risks that could eventually affect foreign investment and aid flows—both important to Rwanda’s development model.

The Institute for Security Studies raises fundamental questions about long-term stability: Would a buffer zone or territorial arrangement freeze conflict or institutionalize a fault line between Rwanda and the DRC? Can short-term economic gains from resource access compensate for human, financial, and reputational costs of prolonged territorial control? If other states emulate Rwanda’s model—prioritizing military power over collective security—what would African regional order become?

5. Conclusion

Rwanda’s economic and political status in East Africa embodies profound contradictions. Economically, it stands as one of the region’s brightest performers, achieving sustained high growth, currency stabilization, and financial sector deepening while managing inflationary pressures through orthodox monetary policy. Its development strategy, articulated through national dialogue processes and implemented with administrative efficiency, offers lessons for other African countries seeking to accelerate structural transformation.

Politically, however, Rwanda has emerged as the most disruptive force in contemporary East African affairs. Its military support for M23 rebels in eastern DRC has created a humanitarian crisis, displaced hundreds of thousands, and brought it into confrontation with regional partners including South Africa and Burundi. President Kagame’s public questioning of the East African Community’s relevance reflects deep frustration with multilateral processes that, in his view, prioritize process over results.

These two dimensions are not contradictory but complementary expressions of a single strategic vision. Rwanda’s domestic success provides the resources and legitimacy that enable regional assertiveness. Its military dominance secures access to resources and creates deterrence against perceived threats. Its international brand as a reliable partner generates diplomatic space that constrains external responses to its regional interventions.

The question facing East Africa is whether this combination is sustainable. Rwanda has demonstrated that a small state can, through organizational discipline and strategic clarity, project power far beyond what its economic size would suggest. But military dominance does not equal regional leadership, which requires the consent—or at least acquiescence—of neighbors. If Rwanda’s strategy provokes lasting opposition from regional partners and erodes the cooperative frameworks that underpin East African integration, it may ultimately undermine the very stability on which its economic success depends.

For the East African Community, the Rwanda crisis represents an existential test. If the community cannot manage conflict between its own members, its aspirations toward deeper integration ring hollow. The challenge is not simply to mediate between Kigali and Kinshasa, but to build regional institutions capable of addressing the security concerns that drive Rwanda’s assertive posture—including the continued presence in eastern DRC of armed groups originating from Rwanda’s genocide. Without addressing root causes, no amount of diplomatic process will produce lasting peace.

Rwanda’s status in East Africa thus remains unresolved: an indispensable economic partner, a challenging security neighbor, and a test case for whether regional integration can contain the competing ambitions of sovereign states. The answer will shape not only Rwanda’s future but that of the East African Community as a whole.

References

Hakuziyaremye, S. (2026, February 18). The Rwanda Central Bank decided to increase its rate by 50 basis points to 7.25 percent. RNA NEWS.

CGTN. (2026, February 11). Rwanda plans constitutional change to hold presidential and parliamentary polls together.

RNA NEWS. (2026, January 13). Edda Mukabagwiza from Rwanda leads EAC election observation mission in Uganda.

Buchanan-Clarke, S. (2026, February 11). Global response needed to stem Rwanda’s DRC agenda. Legalbrief/Mail & Guardian.

Businessday NG. (2026, February 18). Rwanda defies Africa’s easing cycle, hikes policy rate to near 3-year high.

Xinhua. (2026, February 5). Rwandan President Kagame urges faster progress, self-reliance at National Dialogue Council.

Uganda Radionetwork. (2026, February 15). What Kagame Told EAC Leaders’ Summit on DRC Crisis.

Xinhua. (2026, February 19). Rwanda’s central bank raises key rate to 7.25 pct as inflation pressures persist.

Handy, P-S. (2026, January 26). Rwanda: a ‘smart power’ without a regional peace strategy. Institute for Security Studies.

Xinhua. (2026, February 6). Rwandan president urges faster progress, self-reliance at National Dialogue Council.