Abstract

As of early 2026, the Republic of Senegal stands at the most critical inflection point in its contemporary history. Once heralded as a beacon of West African stability, democratic maturity, and emerging market promise, the nation has been plunged into a profound multidimensional crisis. This paper provides a deeply researched analysis of Senegal’s economic and political status, synthesizing the most recent sovereign rating actions, parliamentary outcomes, fiscal disclosures, and policy declarations available through February 2026.

The central finding is stark: Senegal is experiencing a simultaneous collapse of its economic foundation and a radical restructuring of its political order. Economically, the country confronts a debt-to-GDP ratio of approximately 130-132% —a level that places it as the second-most indebted low- and middle-income country globally and positions it for a near-certain sovereign debt restructuring absent an unprecedented rescue. This crisis is not the result of exogenous shocks alone, but of a decade of unsustainable expenditure growth masked by systematic fiscal misreporting, culminating in the revelation of approximately $13.3 billion in hidden debt —the largest financial misrepresentation scandal in West African history.

Politically, Senegal has undergone a revolutionary transformation. The March 2024 election of President Bassirou Diomaye Faye and Prime Minister Ousmane Sonko, followed by their Pastef party’s acquisition of a supermajority (approximately 75%) in the National Assembly in November 2025, represents a wholesale repudiation of the post-independence political establishment. This new administration has explicitly declared the previous development model—characterized by reckless indebtedness and foreign dependency—to be bankrupt, and has proposed a quarter-century alternative, “Senegal 2050.”

This paper argues that these two crises are inextricably linked. The debt crisis is the economic manifestation of the political regime that was defeated at the ballot box, and the new government’s legitimacy is now contingent on its ability to navigate an exit from this debt trap without sacrificing its mandate for sovereign economic transformation. Senegal’s status in West Africa is defined by this tension: it is simultaneously the region’s most dramatic example of democratic renewal and its most alarming case of fiscal fragility. The outcome of this experiment will carry profound implications for the WAEMU zone, the credibility of the IMF’s surveillance mechanisms, and the viability of resource-led development strategies across the continent.

Introduction

For decades, Senegal occupied a privileged position in the lexicon of African development. It was the “donor darling” of the Sahel, a stable democracy in a volatile neighborhood, a Francophone success story that had never experienced a coup. Its capital, Dakar, served as a hub for international agencies, its technocrats were trusted by multilateral lenders, and its growth trajectory, while modest, was deemed reliable. This narrative has shattered.

The year 2025 constituted an annus horribilis that fundamentally altered Senegal’s trajectory. Within a twelve-month period, the nation witnessed: the revelation that its true public debt was nearly double previously reported figures; the suspension of its IMF program; the successful prosecution of an outsider presidential campaign built on anti-system sentiment; the dissolution of the National Assembly; and the consolidation of a legislative supermajority committed to a “radical break” with the past .

This paper proceeds in four parts. First, it diagnoses the structural origins and current dimensions of Senegal’s debt crisis, including the mechanisms of fiscal concealment and the sovereign rating implications. Second, it analyzes the political revolution of 2024-2026, examining the electoral dynamics, the constitutional confrontation, and the consolidation of Pastef’s mandate. Third, it assesses the contested policy response, contrasting the administration’s ambitious “Senegal 2050” vision with the immediate liquidity constraints and IMF negotiations that will determine its viability. Finally, it situates Senegal’s predicament within the broader West African and global financial context, drawing implications for regional stability, the WAEMU architecture, and the future of sovereign financing in frontier markets.

Part I: The Economic Status – The Collapse of a False Narrative

1.1 The Discovery: Anatomy of a Fiscal Concealment

The Senegalese debt crisis is distinguished not merely by its magnitude, but by the mechanism of its revelation. In mid-2024, the incoming administration of Bassirou Diomaye Faye commissioned an audit of public finances that uncovered systematic underreporting of fiscal deficits and public debt under the administration of former President Macky Sall . The findings, formally published by the Cour des Comptes in February 2025, were seismic .

Between 2019 and 2023, the true average fiscal deficit was approximately 11% of GDP, not the 5.5% previously communicated to multilateral partners and markets. Public debt at the end of 2023 was approximately 25 percentage points of GDP higher than reported. Successive revisions throughout 2025 worsened the picture. By year-end, official government estimates placed public debt at 119% of GDP . The IMF, consolidating state-owned enterprise liabilities and domestic expenditure arrears, assessed total public-sector debt at approximately 132% of GDP . Independent analysis by the Finance for Development Lab confirmed that Senegal’s debt had been underestimated by a cumulative margin that erased a decade of presumed fiscal prudence .

The scale of this misrepresentation is without precedent in West Africa. The $13.3 billion in undisclosed liabilities dwarfs Mozambique’s “tuna bond” scandal by a factor of ten . Critically, a significant portion of this concealed debt was accumulated by state-owned enterprises operating outside conventional multilateral surveillance, exposing a systemic vulnerability in the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Framework .

1.2 The Debt Profile: A Rare and Perilous Position

Senegal’s current debt burden places it in an exceptionally dangerous category. With a debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 130%, it ranks second only to China among low- and middle-income countries with populations exceeding one million. According to comprehensive historical analysis, of 36 episodes since 2000 in which developing countries sustained debt ratios above 100% of GDP for multiple years, all but one (Antigua and Barbuda, 2001-2004) were resolved through restructuring or default .

The composition of the debt compounds the risk. Approximately 68% is external, and of that external portion, 41% (XOF 6.6 trillion, or $11.6 billion) is classified as commercial debt. Nearly half of this commercial exposure is in Eurobonds . This shift toward private, non-concessional borrowing is a recent phenomenon: the share of public debt owed to private creditors increased from 19% in 2014 to 42% in 2024, while official creditor exposure declined correspondingly . Senegal thus entered its crisis with expensive, hard-currency obligations held by a diffuse and potentially less cooperative creditor base.

The debt service burden has become crippling. Total debt service now exceeds 10% of Gross National Income—more than double the Sub-Saharan African average and nearly triple the mean for low- and middle-income countries . The interest-to-revenue ratio has climbed to approximately 25% , a level that severely constrains discretionary spending . With $4.6 billion in external debt service due in 2026 —including a Eurobond amortization in March—liquidity pressures are immediate and acute .

1.3 The Macroeconomic Consequences: Growth, Ratings, and Market Access

The immediate aftermath of the debt revelation was a cascade of adverse consequences. The IMF suspended disbursements under its existing program in October 2024, triggering a suspension of certain World Bank and African Development Bank lending. Net transfers from multilateral development banks turned negative for the first time in years .

Sovereign credit ratings collapsed. S&P Global Ratings downgraded Senegal’s long-term foreign currency rating to ‘CCC+’ —deep speculative-grade territory—and placed the rating on CreditWatch developing, indicating the possibility of further downgrade or default classification . Moody’s took parallel actions . Senegal’s Eurobonds traded at distressed levels; the 2048 notes fell to 58 cents on the dollar . Effective access to international capital markets was lost.

Economic growth, while still positive, has been revised downward substantially. S&P revised its 2025 GDP growth forecast from 8.0% to 6.8% , citing anticipated declines in public consumption and investment . The 2026 budget projects growth of approximately 5.0% . This moderation is notable because it coincides with the commencement of hydrocarbon production—the Sangomar oil field became operational in June 2024, and the Greater Tortue Ahmeyim (GTA) gas project followed in December 2024. First-quarter 2025 growth reached 12.1%, demonstrating the immediate impact of these extractive sectors. Yet the underlying growth trajectory, stripped of hydrocarbon volatility, remains weak .

A critical comparative insight emerges from benchmarking Senegal against its WAEMU peers, Benin and Côte d’Ivoire. Both countries achieved stronger and more sustained post-pandemic recovery than Senegal, with real GDP growth stabilizing at 6.5% or above during 2021-2024. Senegal’s average growth remained below 5.5% over the same period. Critically, Benin and Côte d’Ivoire achieved superior growth outcomes while maintaining far more contained fiscal deficits and debt levels below 60% of GDP . This evidence fundamentally undermines any retrospective justification of Senegal’s borrowing spree as necessary investment for growth. The efficiency of public investment was exceptionally low; the marginal growth return on additional expenditure deteriorated markedly .

1.4 Structural Drivers: Expenditure without Transformation

The debt crisis is not an accident of accounting; it is the logical outcome of a specific development model pursued for a decade. Senegal’s fiscal strategy was characterized by three interlinked patterns: (i) a steady and dramatic rise in public expenditure, (ii) broadly stagnant government revenue as a share of GDP, and (iii) worsening fiscal balances financed exclusively by debt .

Total investment as a share of GDP reached extraordinary levels, exceeding 45% in 2022-23—a ratio rarely observed in comparable economies and far exceeding domestic absorptive capacity. Yet this investment surge did not translate into commensurate growth acceleration. The economy remained consumption-driven, import-dependent, and structurally constrained by high energy costs, a narrow industrial base, and insufficient human capital development. Public financial management suffered from weak project selection, implementation delays, and, as subsequently revealed, deliberate opacity .

The previous administration’s defense—that borrowing financed critical infrastructure—is belied by the fact that debt accumulated far faster than productive capacity. Senegal now faces the worst of both worlds: a debt burden characteristic of a developed economy with reserve currency status, and the growth profile of a low-income country with limited policy flexibility .

Part II: The Political Status – Revolution, Consolidation, and the Weight of Expectation

2.1 The 2024 Election: Rupture and the Rejection of Continuity

The political context of Senegal’s debt crisis is inseparable from its electoral calendar. In February 2024, President Macky Sall attempted to postpone the presidential election, citing disputes over candidate disqualifications. This move triggered mass protests, international condemnation, and a constitutional crisis . The image of opposition MPs being ejected from the National Assembly and protestors teargassed outside the building marked a rupture with Senegal’s self-image as a democratic exemplar.

The crisis was resolved through the intervention of the Constitutional Council and intense domestic and international pressure. However, the delay attempt indelibly associated the outgoing administration with anti-democratic maneuvering. When the election was finally held in March 2024, the result was a repudiation: Bassirou Diomaye Faye, an anti-establishment candidate who had been jailed just ten days before the vote, won outright in the first round . His mentor, Ousmane Sonko—the firebrand opposition leader whose disqualification had triggered the initial crisis—became Prime Minister.

This was not a routine alternation of power. Faye and Sonko’s campaign was explicitly revolutionary. They promised a “radical break” with the political and economic system that had governed Senegal since independence. They denounced the “reckless indebtedness” of the Sall years, the opacity of extractive sector contracts, and what they characterized as neocolonial economic relationships . Their electoral coalition, Pastef (Patriotes africains du Sénégal pour le travail, l’éthique et la fraternité), was not a traditional party but a movement animated by generational anger at unemployment, exclusion, and perceived elite impunity.

2.2 The Consolidation of Power: From Co-Habitation to Supermajority

For the first six months of the Faye administration, governance was characterized by tension between an executive committed to radical reform and a parliament still dominated by the opposition. The 165-member National Assembly, elected under the previous dispensation, was hostile territory. Sonko, in his capacity as Prime Minister, was unable to deliver his general policy speech—a constitutional obligation—without facing parliamentary obstruction .

President Faye’s response was decisive. In September 2025, he dissolved the National Assembly and called snap elections for November 17, 2025 . This was a high-risk gamble, but it reflected an accurate reading of the national mood. The electorate, having delivered the presidency to Pastef, was prepared to complete the realignment.

The result was a landslide of historic proportions. Provisional results indicated that Pastef would secure between 119 and 131 seats in the 165-member chamber—approximately 75% of the total . The opposition coalition, Takku Wallu, which had broadened to include former President Abdoulaye Wade’s PDS and Idrissa Seck’s Rewmi, was reduced to approximately 15 seats .

This outcome transformed Senegal’s political landscape. The National Assembly, once an obstacle to the government’s agenda, became its instrument. President Faye acquired an unambiguous mandate for the remainder of his four-year term. Prime Minister Sonko, who had aggressively advocated for the early election, emerged with his influence over government substantially strengthened .

2.3 The Institutional Agenda: Transparency, Control, and “Maturity”

The acquisition of a supermajority does not automatically translate into effective governance. However, the Pastef leadership and parliamentary hierarchy have articulated a clear institutional agenda for 2026. Malick Ndiaye, the President of the National Assembly, has committed the legislature to accompanying the government’s “global reforms” through “rigorous monitoring and evaluation of public policies” .

Ndiaye’s language is significant. He speaks of transitioning “from the normative framework to operational action, then to a clearly assumed strategic vision.” He envisions a National Assembly that is “modern, influential, credible, close to citizens and a driver of democratic transformation,” anchored in “transparency, democratic accountability, and the effectiveness of public action” .

This discourse of institutional modernization—including the introduction of electronic voting systems, digital document management, and enterprise resource planning software—reflects a deliberate attempt to distinguish the new parliamentary era from the opacity and clientelism associated with the previous regime. Ndiaye explicitly invokes “the trust renewed by the Senegalese people” as the mandate for this transformation .

Yet the same supermajority that enables efficiency also eliminates the friction of legislative opposition. The “maturity” praised by the Assembly President may also reflect the absence of meaningful parliamentary checks on executive action. The relationship between Faye and Sonko—two figures who emerged from the same political movement but whose personal ambitions and strategic instincts are not identical—will be the single most important determinant of whether this concentration of power produces effective reform or internal fragmentation .

2.4 Transitional Justice and the Legacy Question

The political revolution has not yet resolved the question of accountability for the fiscal misrepresentation that enabled the debt crisis. The previous administration, led by Macky Sall, has denied manipulating financial figures . No senior officials from the Sall era have faced prosecution or formal sanction in connection with the debt concealment.

This impunity gap is politically unsustainable. The Faye-Sonko campaign was predicated on the claim that the old elite had looted the state and lied to the nation. A failure to pursue accountability risks alienating the government’s base and validating opposition claims that the new administration is merely a generational rotation without substantive change. However, aggressive prosecutions could be framed as political vengeance, potentially destabilizing the fragile consensus that has enabled the democratic transition to proceed without violent rupture.

The administration’s approach to this dilemma remains ambiguous. Unlike in The Gambia, where ECOWAS intervened to establish a special tribunal for Jammeh-era crimes, Senegal’s regional standing and institutional capacity suggest domestic mechanisms will be preferred. Whether the National Assembly’s oversight powers are deployed to investigate the debt concealment—and whether such investigations produce tangible consequences—will be a critical test of the “renewal” proclaimed by the new leadership.

Part III: The Policy Response – Navigating Between Sovereignty and Survival

3.1 The “Senegal 2050” Vision: Endogenous Development as Ideological Anchor

On February 4, 2026, Prime Minister Ousmane Sonko announced the forthcoming presentation of a new national development plan, “Senegal 2050,” intended to cover the next quarter-century . His language was messianic and rejectionist.

“The development models that have been presented to us or applied to us so far will never be able to develop our country,” Sonko declared. “This is the end of the era of reckless indebtedness used to invest in projects that have nothing to do with building endogenous and sovereign development” .

The plan, as previewed, aims to achieve annual economic growth of 6-7% , triple per capita income by 2050, and substantially reduce poverty. It proposes to structure development around eight integrated economic hubs distributed across the national territory, intended to disperse economic activity beyond the Dakar-Thiès axis. Sonko explicitly invoked Japan as a model—a nation with limited natural resources that achieved development through human capital investment, industrial policy, and technological mastery. “We prefer to be taught how to fish rather than continue to be offered fish,” he said .

The ideological framing is unambiguous. “Senegal 2050” is presented as an act of decolonization—a rejection of externally imposed structural adjustment and donor-driven project lending in favor of nationally owned, long-term strategic planning. It positions the extractive sector not as an end in itself but as a potential catalyst for broader industrial transformation, reversing the historical pattern of resource extraction without local value addition.

3.2 The Immediate Constraint: Fiscal Consolidation and the IMF Negotiation

However, “Senegal 2050” is a plan for the long century. The immediate challenge is survival through 2026. Here, the administration confronts the cruel arithmetic of the debt it inherited.

The 2026 budget, adopted by the National Assembly in November 2025, projects expenditures of 7,433.9 billion CFA francs and revenues of 6,188.8 billion CFA, yielding a deficit of 5.37% of GDP . This represents a sharp compression from the 10-12% deficits of recent years, but it falls far short of the 3% target the government has committed to achieving by 2027 . S&P Global projects a more pessimistic trajectory, forecasting deficits of 8.1% in 2026 and 6.8% in 2027 , with debt-to-GDP peaking at approximately 121.5% before stabilizing .

The budget’s revenue assumptions are ambitious. It projects a 23.4% increase in revenues compared to the 2025 finance law, raising the tax-to-GDP ratio from 19.3% to 23.2% —a dramatic increase in fiscal pressure . This is to be achieved through a combination of new tax measures—including levies on mobile money, online gaming, tobacco, and alcoholic beverages—and improved collection efficiency . Expenditure is projected to rise by 12.3%, with capital expenditure surging by 45% following a 2025 slowdown—a reflection of the administration’s determination to avoid an investment drought even under fiscal duress .

The credibility of these projections is highly uncertain. New taxes in emerging sectors have unproven revenue potential. Expenditure arrears, a chronic problem under the previous administration, are still being quantified and may yet inflate the true deficit . Moreover, the budget assumes sustained access to financing that is no longer assured.

This is the context for the administration’s fraught negotiations with the International Monetary Fund. Senegal requires a new IMF program to unlock concessional financing, catalyze other multilateral and bilateral support, and signal credibility to markets . However, the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Analysis framework presents an almost insurmountable obstacle. Under realistic scenarios, Senegal’s external debt service-to-revenue ratio is projected to remain above 50% through 2028 —more than double the 23% threshold deemed “safe”—and is not projected to fall below that level until approximately 2040 .

This is the central paradox: Senegal cannot achieve debt sustainability without an IMF program, but it cannot pass the IMF’s debt sustainability test without first restructuring its debt. The logical solution—a preemptive restructuring under the G20 Common Framework—has been publicly rejected by Prime Minister Sonko, who stated in mid-January 2026 that Senegal would not accept IMF restructuring recommendations .

3.3 The Restructuring Question: Gambling for Redemption?

Sonko’s rejection of an immediate restructuring represents a high-stakes “gamble for redemption.” The administration is seeking to avoid the stigma, legal complexity, and financing freeze associated with a formal default. It is attempting to navigate a narrow corridor defined by three conditions: (i) a fiscal consolidation severe enough to reassure creditors but not so severe as to collapse growth and revenue; (ii) large-scale refinancing from partners willing to accept sovereign risk at below-market rates; and (iii) sustained political tolerance for austerity among a population that elected this government on a promise of radical improvement .

The probability of successfully threading this needle is low. Senegal’s rollover calendar concentrates pressure in 2026, beginning with the March Eurobond maturity. Continued reliance on the WAEMU regional market—which supplied 47% of 2025 financing—carries escalating costs. Regional bond issuance now requires yields exceeding 7% , approximately 200 basis points above the government’s 2024 average cost of debt, and features shorter maturities than concessional loans . This strategy shifts liquidity risk onto the regional banking system, potentially creating a sovereign-bank “doom loop” that could destabilize the entire WAEMU zone .

The alternative path—an IMF-supported restructuring under the Common Framework—carries different but equally severe risks. It would trigger a default rating, temporary exclusion from Eurobond markets, and prolonged negotiations with a fragmented creditor committee. However, the empirical evidence strongly favors early, comprehensive treatment over delayed, piecemeal approaches. Countries that “gamble for redemption” almost invariably end up restructuring later under worse conditions, having accumulated additional arrears and exhausted policy credibility .

3.4 Regional Stabilization: The BCEAO and Systemic Risk

Any resolution of Senegal’s crisis necessarily involves the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO). This is not merely a matter of policy preference but of systemic necessity.

Senegal’s domestic public debt is overwhelmingly held by WAEMU banking institutions. A default or severe mark-to-market loss on these securities would trigger a banking liquidity shock, a contraction in private sector credit, and a high probability of regional contagion. Other WAEMU sovereigns would face sudden reassessments of their own creditworthiness, potentially closing market access for the entire bloc .

In this context, leading economists at the Islamic Development Bank Institute have proposed an exceptional, temporary, and strictly circumscribed stabilization facility under BCEAO leadership. This would involve selective secondary market operations or liquidity facilities backed by high-quality public securities. The purpose would not be to finance fiscal deficits but to prevent disorderly deleveraging and stabilize the government securities market. Such a mechanism would also help reduce the crowding-out effect exerted by large sovereign issuances on private-sector credit—a chronic constraint on WAEMU economic diversification .

The BCEAO’s willingness to deploy such instruments remains untested. Its mandate prioritizes monetary stability and the preservation of the CFA franc peg, guaranteed by France’s unlimited convertibility commitment. A liquidity backstop for Senegal could be framed as consistent with that mandate; it could equally be resisted as moral hazard. The outcome of internal BCEAO deliberations will be decisive.

Part IV: Regional and Global Implications

4.1 Senegal as a Test Case for the Common Framework

Senegal’s predicament arrives at a moment of maximum strain on the international sovereign debt resolution architecture. The G20 Common Framework, established in 2020 to address pandemic-related debt vulnerabilities, has been widely criticized as slow, creditor-coordination failures having marred the Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia cases.

Senegal represents a more complex test. Unlike Zambia, whose debt was predominantly to official bilateral creditors (notably China), Senegal’s exposure is heavily tilted toward private bondholders. Coordinating these disparate creditor classes under the Common Framework’s comparability of treatment principle has proven exceptionally difficult in prior cases. A successful resolution would vindicate the architecture; failure would accelerate the trend toward bilateral, collateralized, and opaque financing arrangements that undermine multilateral surveillance .

4.2 The Geopolitical Dimension: Washington, Beijing, and the Shift in Leverage

The crisis unfolds against a backdrop of shifting great-power engagement with Africa. January 2026 saw the continuation of a trend identified by Chatham House analysts: “weakened multilateral norms and divided international leadership have created a more permissive environment where external accountability has become secondary to transactional interests” .

The United States’ Africa policy is entering a period of uncertainty, with AGOA renewal prospects unclear and diplomatic bandwidth constrained. Traditional Official Development Assistance from Western donors is declining in real terms. China, meanwhile, maintains its zero-tariff policy for African exports and continues to offer infrastructure financing, albeit with increasing selectivity. Beijing’s role in Senegal’s debt resolution—as the second-largest bilateral creditor after France—will be closely scrutinized .

The Faye-Sonko administration has sought to diversify its international partnerships, with high-profile state visits to China, Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and France, alongside participation in international investment forums that secured $23.5 billion in commitments in October 2025 . This suggests a more pragmatic approach to foreign capital than the revolutionary rhetoric might imply. However, translating commitments into disbursements requires sovereign creditworthiness, which remains impaired.

4.3 The Resource Curse Avoidance Test

Senegal’s hydrocarbon sector, long touted as the solution to its development challenges, is now a source of additional complexity. Production has commenced, but the revenue stream will be neither as large nor as immediate as previously advertised. Moreover, the government’s insistence on renegotiating contracts with extractive majors—a central campaign promise—has created uncertainty that may deter the investment needed to expand production .

The administration’s framing of Japan as a development model implicitly acknowledges the insufficiency of resource extraction as a development strategy. Yet the temptation to treat oil and gas revenues as the answer to fiscal pressures will intensify as debt service consumes an expanding share of budget resources. Whether Senegal can avoid the “resource curse” that has afflicted so many African petrostates—corruption, Dutch disease, elite capture—will depend on the robustness of the institutional frameworks the new administration is only beginning to construct.

Conclusion: The Weight of 2026

Senegal in early 2026 is a nation engaged in three simultaneous, overlapping, and partially contradictory projects.

The first is a project of truth-telling. The revelation of the debt concealment, the public acknowledgment of the previous model’s bankruptcy, and the explicit rejection of opaque, elite-driven governance constitute an attempt to establish a new foundation of transparency. The National Assembly’s commitment to “rigorous monitoring and evaluation” and the government’s promotion of a 25-year national strategy are expressions of this impulse .

The second is a project of survival. With debt at 132% of GDP, external payments falling due, and market access constrained, the government must prevent a disorderly liquidity crisis from becoming a solvency crisis that wipes out the developmental gains of previous decades. This requires navigating the narrow corridor between austerity severe enough to satisfy creditors and growth sufficient to sustain political consent .

The third is a project of transformation. “Senegal 2050” is not a conventional development plan; it is an assertion of sovereignty. It rejects the premise that Senegal’s trajectory must be determined by external actors, whether multilateral lenders, bilateral donors, or foreign investors. It insists that a small West African nation can chart its own course, based on its own resources and the capabilities of its own people .

These three projects are not necessarily compatible. Truth-telling undermines the confidence that survival requires. Survival pressures incentivize the short-term expedients that transformation seeks to abolish. Transformation demands a patience and policy coherence that the immediacy of the debt wall does not permit.

The next twelve months will determine which of these projects prevails. The March 2026 Eurobond maturity is a liquidity test; the IMF negotiations are a credibility test; the 2026 budget execution is an administrative test; and the relationship between Faye and Sonko is a political test. Failure on any of these fronts could trigger a cascade that overwhelms the others.

Yet it is also possible that Senegal’s simultaneous crises will prove mutually reinforcing. The debt shock has created the political space for reforms that would have been inconceivable under normal circumstances. The democratic mandate of the Faye-Sonko administration is genuine and deep. The institutional capacity of the Senegalese state, while strained, is more robust than in most of its regional peers. The WAEMU framework, for all its constraints, provides a stability anchor unavailable to standalone monetary authorities.

Senegal’s status in West Africa is thus one of concentrated significance. It is the region’s most dramatic democratic success story—and its most alarming fiscal failure. It is the testing ground for whether a resource-rich, democratically mandated, anti-system government can reconcile the demands of international creditors with the aspirations of its domestic constituency. It is the case that will either restore or further erode confidence in the multilateral debt resolution architecture.

The path Senegal charts in 2026 will not determine its fate alone. It will shape the possibilities available to every West African nation seeking to navigate between the imperative of development and the discipline of debt, between the promise of sovereignty and the constraints of interdependence. The region watches Dakar with an attention that is both anxious and hopeful.

Sources:

- APS – Agence de Presse Sénégalaise

- IsDBI BLOG

- Invest Africa

- S&P Global

- Africa Confidential

- New Age BD

- Stears West Africa Economic Outlook: 2026

- VoxDev

Related Posts

Political Instability & Democratic Backsliding in Africa

Introduction: The Promise and the Peril The early 1990s marked…

The Economic Ambition and Political Complexity of Cameroon

Abstract: The Republic of Cameroon occupies a unique and often…

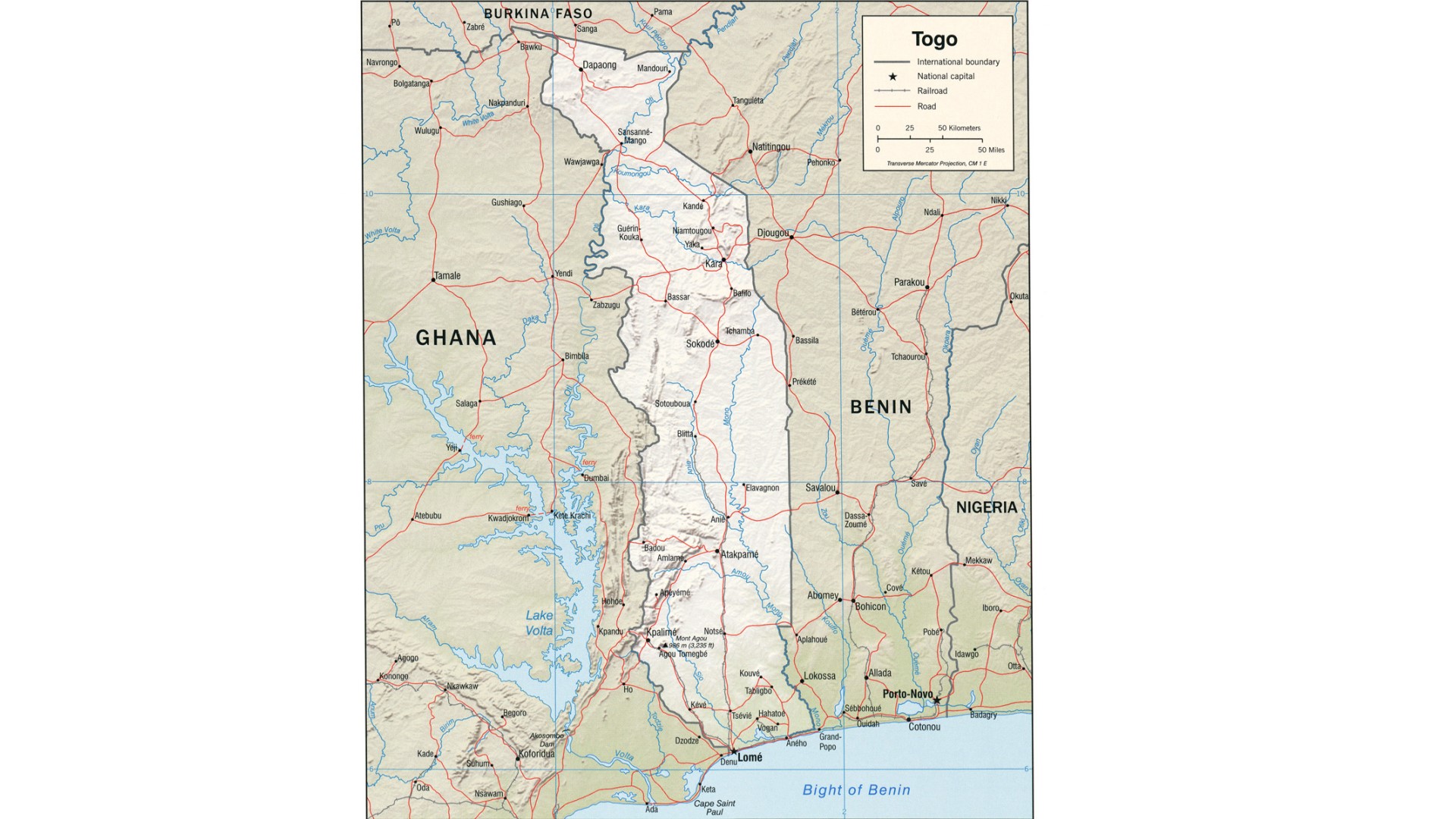

Togo in A Nexus of Stability, Vulnerability, and Dynastic Governance

Abstract: This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the contemporary…