Abstract:

The Republic of Cameroon occupies a unique and often paradoxical position in West and Central Africa. Though geographically situated in Central Africa, Cameroon is a member of both the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a dual affiliation that underscores its regional ambiguity and strategic bridging role. This paper provides a deeply researched analysis of Cameroon’s contemporary economic and political status, examining its potential as an economic hub constrained by profound governance challenges, a fraught security environment, and deep-seated political instability. It argues that Cameroon’s trajectory is defined by the tension between its considerable economic assets and its brittle, centralized political system, which collectively shape its influence and stability within the region.

1. Introduction: The “Africa in Miniature” in Regional Context

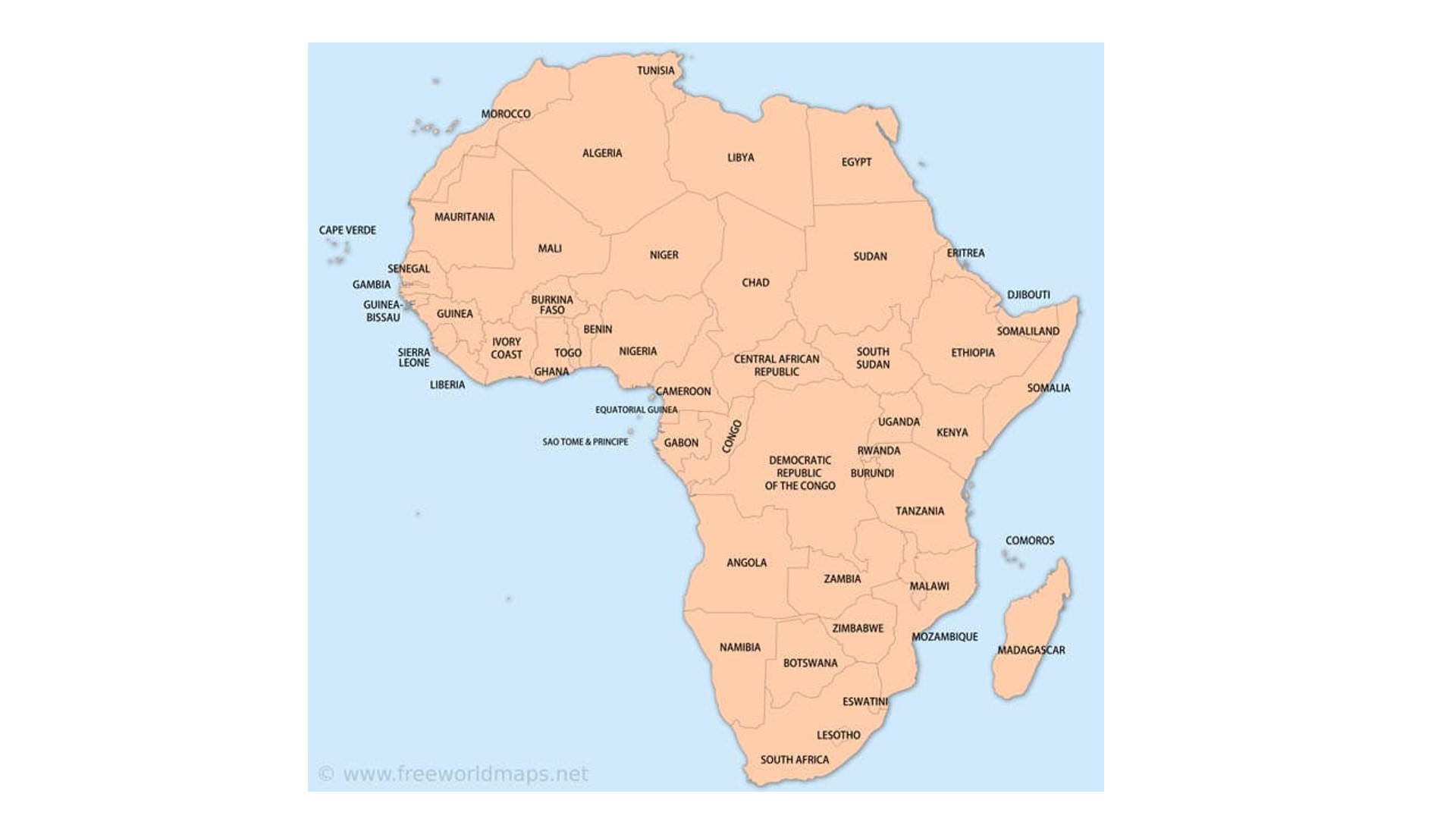

Cameroon is often termed “Africa in miniature” for its geographic and cultural diversity, encompassing coastlines, rainforests, savannahs, and mountains, as well as Anglophone and Francophone legacies. This diversity, however, complicates its national cohesion and regional categorization. While the CIA World Factbook and the African Union place it in Central Africa, its economic and historical ties with Nigeria and inclusion in ECOWAS make its West African status a matter of functional analysis. This paper adopts a pragmatic view, assessing Cameroon’s role within the West African sphere due to its active ECOWAS membership and significant cross-border interactions.

2. Economic Status: Potential, Structure, and Challenges

2.1 Macroeconomic Overview and Sectors

Cameroon is the largest economy in the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), with a GDP of approximately $45 billion (2022 est.). It has experienced modest but stable growth, averaging around 4% annually pre-COVID-19, driven by commodities, agriculture, and services. However, per capita GDP remains low ($1,650), and poverty affects nearly 40% of the population.

-

Primary Sector: Agriculture employs about 60% of the workforce and contributes 16% of GDP. Cameroon is a net food producer and a major exporter of cocoa, coffee, banana, and cotton. Oil and gas, while contributing roughly 30% of fiscal revenues, have seen declining production.

-

Secondary & Tertiary Sectors: Limited industrialization focuses on agro-processing, aluminum, and timber. The services sector, particularly telecommunications and informality, is growing. Major infrastructure projects, like the deep-sea port at Kribi (built with Chinese financing), aim to position Cameroon as a gateway for landlocked neighbors like Chad and the Central African Republic.

2.2 Regional Economic Integration

Cameroon’s dual membership in ECCAS and ECOWAS is strategically unique. Within ECOWAS, it is a significant, if sometimes peripheral, actor:

-

Trade: Nigeria is Cameroon’s largest regional trading partner, though formal trade is overshadowed by extensive informal cross-border commerce.

-

Monetary Policy: As a member of CEMAC (which uses the CFA franc pegged to the Euro), Cameroon operates outside the ECOWAS single currency ambitions, creating a monetary divide with its West African neighbors.

-

Gateway Role: Infrastructure development, particularly railways and ports, is geared towards capturing transit trade for the interior, competing with ports in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria.

2.3 Structural Vulnerabilities

The economy faces significant headwinds:

-

Over-reliance on Commodities: Makes it vulnerable to price shocks.

-

Poor Business Climate: Ranked 167th in the World Bank’s Doing Business Index (2020), due to bureaucracy, corruption, and weak judicial enforcement.

-

Debt Distress: Public debt rose to over 45% of GDP, with a significant portion owed to Chinese creditors for infrastructure, raising concerns about debt sustainability.

-

Energy Deficit: Despite hydro potential, unreliable electricity stifles industrial growth.

3. Political Status: Stability, Centralization, and Conflict

3.1 Centralized Governance and the Biya Regime

Cameroon has been under the continuous rule of President Paul Biya since 1982, making him one of the world’s longest-serving leaders. The political system is characterized by hyper-presidentialism and the dominance of the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM). Key features include:

-

Executive Dominance: The presidency controls all levers of power, with weak checks from the legislature and judiciary.

-

Patronage Networks: The state operates largely through ethnoregional patronage, with stability purchased through the distribution of resources, a system now strained by economic constraints.

-

Perception of Corruption: Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index consistently ranks Cameroon among the most corrupt nations (142nd out of 180 in 2021).

3.2 The Anglophone Crisis: A Threat to National Unity

The most severe political challenge is the ongoing conflict in the Northwest and Southwest Regions (the Anglophone regions). Rooted in the marginalization of the English-speaking minority following the post-colonial union with Francophone Cameroon, the crisis escalated in 2016-17. A government crackdown on peaceful protests led to the radicalization of separatists, who now seek an independent state of “Ambazonia.” The conflict has resulted in:

-

Humanitarian Catastrophe: Over 6,000 deaths, 600,000 internally displaced, and 80,000 refugees in Nigeria (UN estimates).

-

Economic Devastation: Key economic zones (agriculture, rubber, oil) have been disrupted, and the port of Limbe is affected.

-

Security Drain: The military is locked in a costly, brutal stalemate with numerous separatist militias, accused of human rights abuses by international NGOs.

3.3 Regional Security and Foreign Policy

Cameroon’s security apparatus is also engaged against Boko Haram incursions from Nigeria in the Far North, as part of the Multinational Joint Task Force. This multi-front security crisis drains public funds and humanitarian resources. Regionally, Cameroon projects itself as a pillar of stability in CEMAC but is often viewed with caution in ECOWAS circles due to its governance model and the Anglophone crisis.

4. Cameroon’s Regional Standing: Between Two Blocs

Cameroon’s influence is multifaceted:

-

Within CEMAC/ECCAS: It is the de facto leader and economic engine, hosting key regional institutions.

-

Within ECOWAS: It is a secondary player, often aligning with Francophone members but distinct due to its currency and primary Central African focus. The Anglophone crisis has diminished its moral authority and raised concerns about regional spillover.

-

International Partnerships: Maintains strong ties with France (despite growing anti-French sentiment), China (a major creditor and infrastructure partner), and the United States (security cooperation).

5. Conclusion: The Paradox of Potential and Peril

Cameroon’s status in West Africa is that of a pivotal yet precarious state. Economically, it possesses the foundational assets—resources, diversified agriculture, and strategic infrastructure—to be a commercial hub for both West and Central Africa. However, this potential is critically undermined by its political realities: an aging, centralized authoritarian system unable to manage internal diversity or reform, and a devastating conflict that has morphed into a protracted civil war.

For Cameroon to fully realize its economic promise and stabilize its political standing in West Africa, a fundamental political settlement, particularly addressing the Anglophone crisis through inclusive dialogue and decentralization, is imperative. Without such a resolution, Cameroon risks becoming a locus of instability that threatens not only its own future but also the security and economic integration of both the Central and West African regions. Its dual regional membership will remain less an asset and more a reminder of its unresolved national question.

Sources:

-

Achankeng, Fon. Conflict and Conflict Resolution in Cameroon. Langaa RPCIG, 2023.

-

International Crisis Group. “The Anglophone Crisis: How to Get to Talks?” Africa Reports, 2019-2023.

-

Konings, Piet & Nyamnjoh, Francis. Negotiating an Anglophone Identity. Brill, 2003.

-

Mbaku, John Mukum. “Cameroon’s Stalled Democratic Transition.” Journal of Democracy, 2020.

-

World Bank. Cameroon Economic Updates. Various years.

-

African Development Bank. Cameroon Country Strategy Paper. 2022.

-

U.S. Department of State. 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Cameroon.

-

Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index.

-

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Cameroon Humanitarian Response Plans.