Abstract

This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of Malawi’s contemporary economic and political status within the East African region. Drawing on official government addresses, parliamentary records, international financial institution data, and regional diplomatic engagements, it argues that Malawi is navigating a profound dual transition: an ambitious economic recovery program under a newly returned administration, concurrent with a strategic repositioning within Africa’s complex regional architecture. Economically, Malawi demonstrates the paradox of a nation with resilient growth projections—3.8 percent in 2026 and 4.9 percent in 2027—yet trapped in debt distress, with debt servicing consuming over K1.3 trillion annually and foreign exchange reserves persistently below recommended levels . Politically, President Peter Mutharika’s administration, in office only since September 2025, has launched an aggressive reform agenda centered on anti-corruption enforcement, fiscal austerity, and a dramatic expansion of constituency development funding from K220 million to K5 billion per constituency . Regionally, Malawi occupies a unique intersectional position—a member of both the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), while strategically pursuing bilateral trade agreements with East African partners like Rwanda to harness the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) . Infrastructure initiatives, particularly the Nacala Railway Corridor extension, promise to transform Malawi from a landlocked economy into a regional trade hub connected directly to the Indian Ocean . Malawi’s status is thus defined by the tension between immediate fiscal crisis and long-term structural potential—a fragile equilibrium whose resolution depends on sustained reform implementation, continued international partner engagement, and successful navigation of overlapping regional integration frameworks.

1. Introduction: Malawi at the Crossroads of Recovery and Reform

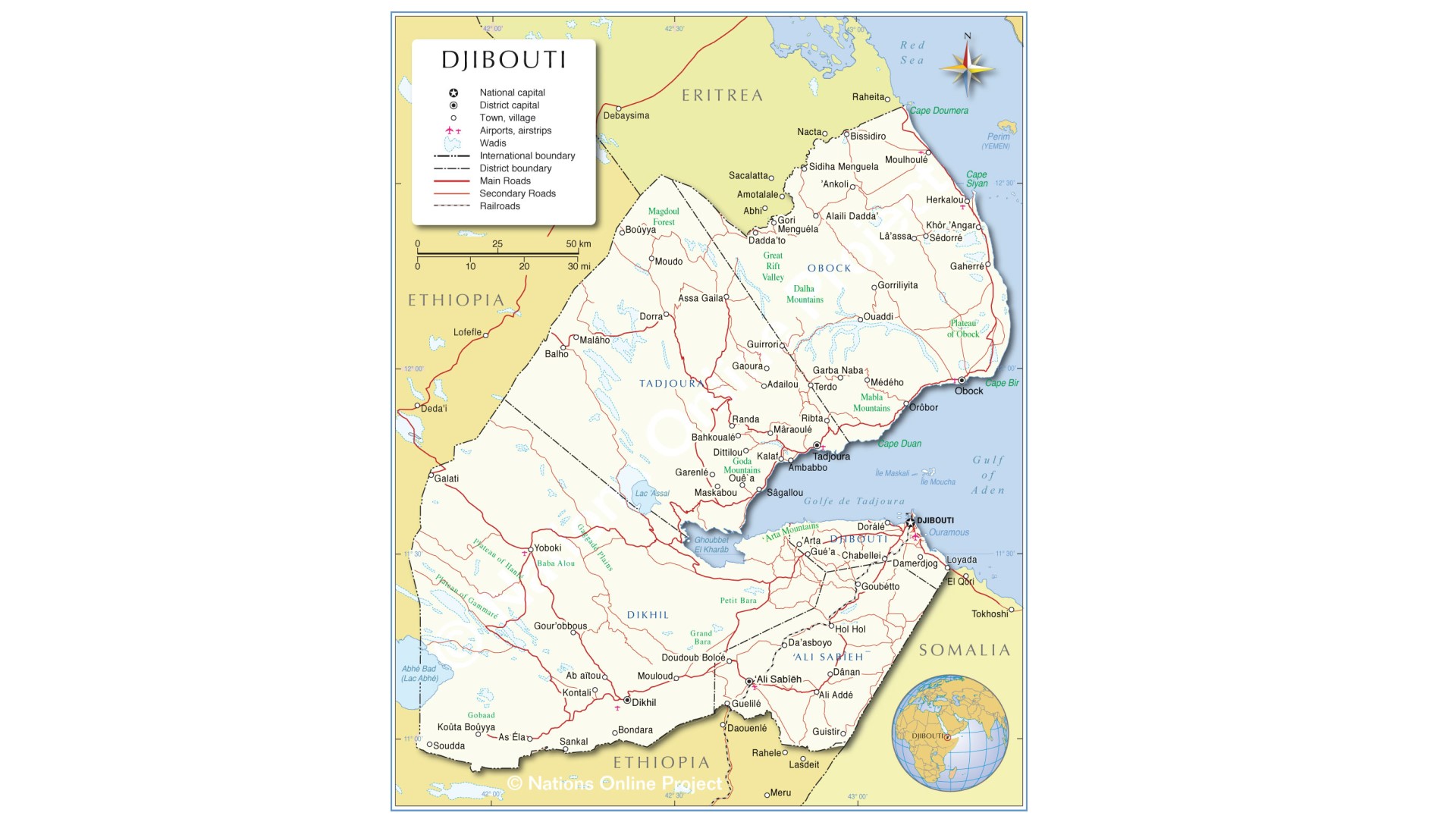

Malawi, the “Warm Heart of Africa,” occupies a distinctive position in the East African landscape. Landlocked and predominantly agrarian, with a population exceeding 21 million, it is neither an economic powerhouse like Kenya nor a demographic giant like Ethiopia, yet its strategic location between Southern, Central, and East Africa renders it indispensable for regional trade integration. Bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest, Malawi functions as a natural corridor connecting landlocked Southern African economies to Indian Ocean ports.

Since September 2025, Malawi has been navigating a significant political transition following the return of President Peter Mutharika to power after the general election. His administration inherited an economy characterized by “high inflation, food shortages, fuel scarcity, foreign exchange challenges, and declining public services” . The new government’s response—articulated in the February 2026 State of the Nation Address (SONA)—represents an ambitious attempt to simultaneously stabilize macroeconomic fundamentals, restore governance integrity, and lay foundations for long-term structural transformation.

This paper contends that Malawi’s contemporary status is best understood through four interconnected lenses: its precarious yet improving economic position, characterized by modest growth projections amid severe debt distress; its political transformation under a newly installed administration pursuing an aggressive reform agenda; its complex regional positioning as a member of overlapping economic communities (COMESA and SADC) while strategically engaging East African partners; and its infrastructure-led integration strategy, anchored by the Nacala Railway Corridor extension, which promises to reshape the country’s role in regional trade. The interplay between these domains defines Malawi’s status as a state whose immediate fragility coexists with substantial long-term potential—a tension whose resolution will shape both its domestic trajectory and its regional significance.

2. Economic Status: Modest Growth Amidst Severe Constraints

2.1 Macroeconomic Trajectory and Growth Projections

Malawi’s economy enters 2026 on a cautiously optimistic trajectory, though significant structural challenges persist. In his February 2026 State of the Nation Address, President Mutharika projected economic growth of 3.8 percent for 2026 and 4.9 percent for 2027, a notable improvement from the 2.7 percent recorded in 2025 . These projections, while modest by regional standards, signal a anticipated recovery from the severe economic contraction of recent years.

Inflation trends offer grounds for measured optimism. The President reported that inflation, which stood at 28.7 percent in September 2025, is projected to decline to below 21 percent in 2026 . This disinflationary trajectory is attributed to declining prices for maize—the national staple—and other essential commodities, including building materials such as cement . The price of a 50kg bag of maize has fallen from approximately K100,000 before the new administration took office to between K38,000 and K55,000 currently .

However, these positive indicators coexist with persistent vulnerabilities. Foreign exchange reserves remain “below the recommended three months’ import cover,” constraining the economy’s ability to absorb external shocks and finance essential imports . The Malawi Confederation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (MCCCI) has welcomed the government’s policy direction while emphasizing that effective implementation of outlined measures is essential to “restore business confidence, improve productivity and stimulate investment” .

2.2 Debt Distress and the IMF Engagement

The most significant constraint on Malawi’s economic recovery is its unsustainable debt burden. Malawi is classified as a country in debt distress, a status that Finance Minister Sosten Gwengwe described as “frustrating because instead of the money going to public services such as water, energy, medicines among others, the country is servicing debts” .

The scale of the debt burden is starkly illustrated by budget allocations. In the 2022/23 fiscal year, K914 billion was expended on debt repayment. The 2023/24 budget allocated K1.3 trillion to debt servicing—funds that might otherwise support healthcare, education, and infrastructure development . According to the International Monetary Fund, Malawi’s outstanding purchases and loans as of March 2023 stood at $326.62 million .

In response to this crisis, the Malawi Government has been actively engaging bilateral creditors to provide financial assurances necessary for debt restructuring and securing a new IMF Extended Credit Facility (ECF) loan. The Minister of Finance reported engagements with the Trade and Development Bank, the Africa Export-Import Bank, and China, as “the IMF wants assurances from all Malawi’s creditors” . The stakes are substantial: should the IMF be convinced by creditor assurances, the World Bank and European Union stand ready to provide $70 million and $350 million respectively .

The World Bank has already demonstrated commitment through its “Malawi First Growth and Resilience DPO with a Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option,” an $80 million development policy operation combined with a $57 million Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option (Cat-DDO). This facility is designed to “help the Government of Malawi address longstanding macroeconomic imbalances, as supported through a new International Monetary Fund program and strengthen structural and governance foundations for a more dynamic and resilient economy” .

Civil society organizations have amplified calls for comprehensive debt relief. Action Aid International has called for “complete debt cancellation” for countries facing the double impact of debt distress and climate change, arguing that this would enable distressed countries “to shape their struggling economies and increase funding for public services such as health” . Malawi qualifies for debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, though since 2020 “there has been no political will for the HIPC initiative at large” .

2.3 Sectoral Dynamics: Agriculture, Energy, and Mining

Agriculture remains the foundation of Malawi’s economy and the central pillar of its recovery strategy. President Mutharika placed strong emphasis on food security, reporting that his government has distributed 65 percent of the targeted 1.1 million beneficiaries of the Farm Inputs Subsidy Programme (FISP), compared to only 45 percent by the same time in the previous year . The President has guaranteed “better and improved delivery of FISP in the 2026/27 farming season” and announced that the Mega Farms Programme will be “reviewed and redesigned” to align with his government’s food security priorities .

The government’s response to the food crisis has been substantial. Having declared a state of disaster in October 2025 due to climate change-induced hunger, the administration mobilized K138 billion of the K209 billion required to assist 4 million Malawians requiring food relief .

Energy infrastructure, positioned as a key economic driver, is targeted for significant expansion. President Mutharika projects power generation will increase from the current 551 megawatts to 1,000 megawatts by 2030. Recent gains include restoration of 31 megawatts at Tedzani Hydro power station, commissioning of 10 megawatts at Raiply Biomass, and installation of 10 megawatts at Nanjoka-Egenco Solar in Salima . The government also aims to double fuel storage capacity from 60 million to 120 million litres .

The mining sector has attracted renewed attention, with the President announcing a suspension of mining license issuance pending an audit of the license registry. The ban on mineral exports remains in effect “to strengthen the capacity to negotiate new mining agreements” . This cautious approach reflects recognition of the sector’s potential alongside determination to avoid the resource governance failures that have plagued other African economies.

2.4 Fiscal Architecture: Austerity and Decentralization

The Mutharika administration has implemented significant fiscal reforms aimed at preserving public resources and enhancing governance transparency. Austerity measures include “reducing fuel entitlements for Cabinet ministers and senior officials and restricting local and international travel” and reducing the number of Principal Secretaries from 80 to 32 .

The most dramatic fiscal initiative, however, is the increase in the Constituency Development Fund (CDF) from K220 million to K5 billion per constituency per year, effective from the 2026-2027 financial year . This 22-fold increase represents a fundamental shift in resource allocation toward local development. To ensure accountability, management responsibility for CDF resources has been shifted to controlling officers in local authorities, and the government has developed CDF guidelines and committed to investing in “a national digital CDF dashboard to give Malawians real-time access to information on CDF utilisation” .

Health and education have received substantial funding increases. The health budget has been augmented by K17 billion, with an additional K5 billion for children’s vaccines. The government has secured a $744 million U.S. grant to strengthen health systems, and has pledged to resolve drug shortages, initiate dialysis services at Mzuzu Central Hospital, and commence construction of Blantyre and Chikwawa District Hospitals . In education, free secondary school implementation is progressing, with 1,800 dropouts returned to school, student loan beneficiaries increased from 32,480 to 38,000, and funding resumed for Mombera University in Mzimba .

3. Political Status: Return, Reform, and Resistance

3.1 The Mutharica Administration: Mandate and Early Actions

President Peter Mutharika’s return to power following the Democratic Progressive Party victory in the September 16, 2025, general election marked a significant political transition. In his first State of the Nation Address, delivered on February 13, 2026, the President declared that his administration had “moved swiftly to confront Malawi’s mounting economic challenges,” asserting that “decisive reforms introduced within four months of taking office are already laying the groundwork for financial stability and renewed growth in the country, something that the previous regime could not manage to do in five years” .

The address, delivered under the theme “Path to Economic Recovery: Delivering a People-Centred Development,” outlined key priorities including macroeconomic growth, agriculture and food security, health, education, public sector reforms, mining reforms, and decentralisation . Governance commentator Enerst Thindwa observed that “people were very much interested in so many aspects, beginning with the economy, because this is the area that was ruined before the election,” adding that Malawians “will now be watching closely to see the continuation of these commitments and how they will translate into action” .

3.2 The Anti-Corruption Offensive

A central pillar of the new administration’s political strategy is an aggressive anti-corruption campaign. President Mutharika issued a stark warning: “Let me make it clear that my Government will arrest anyone involved in corrupt malpractices. Mr. Speaker, Sir, when I say anyone, I mean anyone! It doesn’t matter whether you are a Cabinet Minister, Party official, Member of Parliament, or Government Official. I will shield no one. And there will be no Sacred cows” .

The President reported that in its first four months, his government had “managed to cancel fraudulent contracts in the government and all state-owned enterprises” . He directed all Ministries, Departments, and Agencies to embrace digital technology, asserting that “Malawi’s economy must now be driven by digital systems” and urging citizens to utilize online platforms for passport applications, national identity cards, driving licenses, and public procurement as key to “efficiency, transparency, and inclusive development” .

Public Affairs Committee Chairperson, Rev. Dr. Patrick Semphere, welcomed the anti-corruption stance, stating that “Malawians expect decisive action against corruption and prudent management of public resources” . The Public Affairs Committee also urged the executive to ensure timely appointment of governance oversight bodies, including the Inspector General of Police, Director General of the Anti-Corruption Bureau, and Director of Public Prosecutions .

3.3 Parliamentary Dynamics and Opposition Challenge

The President’s address and reform agenda have encountered robust parliamentary scrutiny. Leader of Opposition Simplex Chithyola Banda criticized the State of the Nation Address as “brief and lacking substance on pressing national concerns,” arguing that Malawians had expected comprehensive attention to “the rising cost of living, soaring fuel prices from about K3,000 to nearly K5,000 per litre, punitive taxation, youth unemployment, and growing insecurity, including abductions” .

Banda specifically questioned the government’s projected economic growth, arguing that “anticipated declines of at least 30 percent in maize and tobacco production could undermine the targets” and that the address “failed to sufficiently outline fiscal policy direction, public debt levels, revenue collection trends, and concrete measures to shield citizens from economic shocks” .

Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Ben Malunga Phiri mounted a forceful defense, accusing Banda of presiding over “a lot of plunder” during his tenure as Finance Minister. Phiri maintained that the State of the Nation Address “is meant to provide policy direction rather than recycle what he characterized as politically motivated criticism” .

3.4 Institutional Continuity and Reform

The transitional government has emphasized administrative continuity alongside political transformation. The appointment of former businessman and experienced minister as Finance Minister signals ongoing engagement with international financial institutions and investors. The government has maintained engagement with the IMF, World Bank, and bilateral donors, recognizing that continued international support is essential for navigating the debt crisis.

Political Science Association of Malawi Publicity Secretary Mavuto Bamusi expressed confidence that the President has “provided a roadmap for economic recovery,” emphasizing that “most importantly, the President has condemned corruption in the strongest terms, and this is what Malawians of goodwill expected” .

4. Regional Status: Between East Africa and Southern Africa

4.1 Overlapping Memberships: COMESA and SADC

Malawi’s regional status is institutionally defined by its membership in two of Africa’s eight recognized Regional Economic Communities (RECs): the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) . This dual affiliation places Malawi at the intersection of Eastern and Southern African regional integration architectures, offering both opportunities and complexities.

COMESA, established by treaty in 1993 and ratified in Lilongwe, Malawi, on December 8, 1994, counts Malawi among its 21 member states spanning North, East, Central, and Southern Africa . COMESA’s mission is “to endeavour to achieve sustainable economic and social progress in all Member States through increased co-operation and integration in all fields of development particularly in trade, customs and monetary affairs, transport, communication and information, technology, industry and energy, gender, agriculture, environment and natural resources” .

Simultaneously, Malawi is a founding member of SADC, the 16-member community focused on promoting “growth and development through consolidation of democracy, peace, security and stability, and through collective self-reliance” . This dual membership reflects Malawi’s geographic position as a bridge between regions but also creates challenges of multiple commitments, overlapping mandates, and the need to harmonize diverse regional integration agendas.

4.2 Bilateral Engagement with East Africa: The Malawi-Rwanda Partnership

Beyond institutional memberships, Malawi is actively cultivating bilateral relationships with East African partners. In February 2026, Minister of Industry, Trade and Tourism Simon Itaye hosted Rwanda’s High Commissioner to Zambia (also non-resident High Commissioner to Malawi), Emmanuel Bugingo, to discuss deepening trade relations .

Minister Itaye emphasized that “trade windows with such economies as Rwanda would help spearhead regional integration, and hasten the realisation of the African Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) aspirations” . The AfCFTA, among the African Union’s flagship Agenda 2063 projects, promises to create the world’s largest free trade area by number of countries, connecting 55 African nations with a customer base of over 1.3 billion people and a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion . Fully implemented, the AfCFTA could increase intra-African trade by up to 110 percent and lift up to 30 million people out of extreme poverty .

High Commissioner Bugingo noted that Rwanda “shares a lot with Malawi and has enjoyed the good relationship the two nations have shared for ages,” adding that deepening trade relations would help both countries grow their economies . Rwanda’s expertise in ICT development, trade in services, tourism, and special economic zones offers lessons for Malawi as it “lays foundations for her own Special Economic Zones as a way of speeding up and scaling out her industrialization dream” .

4.3 Infrastructure Integration: The Nacala Railway Corridor

The most transformative regional integration initiative involving Malawi is the proposed extension of the Nacala Railway Corridor. In late 2025, ministers from Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo signed a ministerial declaration to extend this strategic infrastructure asset, aiming to “connect landlocked economies directly to the Indian Ocean through the Port of Nacala” .

The proposed extension would create an approximately 2,400 km regional rail network “running from Chipata in Zambia through Malawi and Mozambique, with a further extension into the Democratic Republic of Congo” . The Port of Nacala is “one of the deepest natural ports in East and Southern Africa” and is “capable of handling large volumes of bulk and container cargo, making it a strategic gateway for regional trade” .

Ministers from participating countries have agreed to “jointly seek financing and strategic partners,” with an implementation framework expected by early 2026 . The corridor extension is expected to “strengthen regional integration, improve logistics efficiency, and support long term economic development across Southern and Central Africa” .

For landlocked Malawi, this initiative represents a profound opportunity to reduce transport costs, improve trade logistics, and transform its status from a peripheral economy to a central transit corridor. The project also complements digital connectivity initiatives, with fiber optic deployment along transport corridors expected to “integrate the region, fill gaps and close regional and sub-regional connectivity rings, thereby increasing reliability, uptime and redundancy” .

4.4 Comparative Regional Positioning

Malawi’s economic indicators place it in a challenging position relative to East African peers. While Ethiopia projects 10.2 percent growth and Kenya 4.9-5.2 percent, Malawi’s 3.8-4.9 percent trajectory reflects both recovery potential and persistent structural constraints . Its debt distress status contrasts with Kenya’s upgraded credit ratings following fiscal consolidation, though Malawi’s debt is predominantly concessional, offering some protection.

Politically, Malawi’s democratic transition following the September 2025 election distinguishes it from neighbors experiencing military takeovers. Its peaceful transfer of power, robust parliamentary scrutiny, and active civil society engagement align it more closely with Kenya’s established democratic institutions than with countries experiencing constitutional ruptures.

Regionally, Malawi’s dual COMESA-SADC membership offers unique advantages. Unlike Ethiopia (IGAD, COMESA) or Kenya (EAC, COMESA, IGAD), Malawi’s position at the intersection of Eastern and Southern African integration architectures enables it to serve as a bridge between regions . The Nacala Corridor initiative exemplifies this bridging role, connecting landlocked SADC economies to Indian Ocean trade routes through infrastructure that serves both regional communities.

5. Geopolitical Status: Development Partners and Strategic Engagement

5.1 International Financial Institutions and Debt Negotiations

Malawi’s geopolitical significance derives less from strategic resources or military capacity than from its position as a test case for international debt architecture and climate resilience. The country’s engagement with the IMF, World Bank, and bilateral creditors is being closely watched as precedent for other debt-distressed nations navigating the G20 Common Framework.

The IMF’s requirements for creditor assurances before approving a new ECF program have driven intensive diplomatic engagement. Malawi has approached China, the Trade and Development Bank, and the Africa Export-Import Bank to secure necessary commitments . Finance Minister Gwengwe acknowledged the complexity, noting that “other countries like Zambia started this process two years before us, but they are yet to complete the process” .

The World Bank’s $137 million package (combining DPO and Cat-DDO) represents substantial commitment to Malawi’s reform agenda . The operation supports reforms aimed at “strengthening public financial management” and “supporting agricultural commercialization and strengthening the resilience of the poor against shocks” . Its inclusion of a Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option acknowledges Malawi’s extreme vulnerability to climate-related disasters—a vulnerability that is gaining increased international attention.

5.2 Climate Vulnerability and the Resilience Agenda

Malawi is among the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries, a status that shapes both its development challenges and its engagement with international partners. The World Bank’s Country Partnership Framework explicitly addresses this dimension, with the Cat-DDO designed to enhance “the legal and regulatory framework for government to both manage and respond to disaster risks” .

The October 2025 state of disaster declaration due to hunger caused by climate change effects mobilized both domestic resources and international goodwill. President Mutharika reported that “organisations and people of goodwill responded positively to the call,” contributing to the K138 billion mobilized for food relief .

Action Aid International has linked climate vulnerability to debt distress, arguing in its report “The Vicious Circle—Connections between Debt and Climate Crisis” that countries facing both challenges require comprehensive debt cancellation. The organization’s Global Lead on Economic Justice, Roos Saalbrink, called for lending institutions to “change structural procedures to make poor countries in a realistic position to repay the loans,” noting that “low-income countries have been subjected to loan conditions they have had no say on” .

5.3 Traditional Partners and Emerging Actors

Malawi maintains strong relationships with traditional development partners while selectively engaging emerging actors. The United States remains significant, with the $744 million health systems grant announced in the SONA representing substantial commitment . The European Union stands ready to provide $350 million contingent on IMF program approval .

China has emerged as a crucial creditor, with the government actively engaging Beijing for financial assurances necessary for IMF program approval . China’s role in Malawi’s debt restructuring will be closely watched as precedent for other African nations navigating the G20 Common Framework.

The Trade and Development Bank and Africa Export-Import Bank represent regional financing institutions assuming growing importance. Their engagement in providing creditor assurances for IMF programs signals the increasing capacity of African financial institutions to support member states in navigating international debt architecture .

6. Conclusion: The Fragile Equilibrium

Malawi’s economic and political status in early 2026 is defined by a fundamental tension between immediate crisis and long-term potential—a fragile equilibrium whose sustainability depends on multiple intersecting factors.

Economically, the country presents a paradox: modest growth projections (3.8 percent in 2026, 4.9 percent in 2027) and declining inflation (from 28.7 percent to below 21 percent) coexist with severe debt distress, with debt servicing consuming over K1.3 trillion annually and foreign exchange reserves persistently below recommended levels . The government’s engagement with the IMF, World Bank, and bilateral creditors offers a pathway to debt sustainability, but the process is complex and precedent-setting, with no assurance of rapid resolution.

Politically, President Mutharika’s newly installed administration has launched an ambitious reform agenda centered on anti-corruption enforcement, fiscal austerity, and unprecedented expansion of constituency development funding . The anti-corruption offensive has generated significant political capital, though implementation will determine whether rhetorical commitment translates into tangible results. Parliamentary scrutiny and opposition challenge demonstrate democratic vitality while testing the government’s capacity to maintain legislative support.

Regionally, Malawi occupies a unique intersectional position—member of both COMESA and SADC, strategically cultivating bilateral trade agreements with East African partners like Rwanda, and positioned as a central node in the transformative Nacala Railway Corridor extension . The infrastructure initiative, connecting landlocked economies to the Indian Ocean through the Port of Nacala, promises to fundamentally reshape Malawi’s economic geography and regional significance.

Geopolitically, Malawi navigates complex relationships with international financial institutions, traditional development partners, and emerging creditors like China. Its extreme climate vulnerability positions it as a test case for integrating resilience into development finance, with the World Bank’s Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option offering a model for other disaster-prone nations .

The fundamental question for 2026 and beyond is whether Malawi’s reform momentum can be sustained long enough to translate into tangible improvements in citizens’ lives. The government’s ambitious agenda—debt restructuring, anti-corruption enforcement, agricultural transformation, infrastructure investment, and unprecedented local development funding—requires sustained implementation capacity, continued international partner engagement, and political stability. The fragile equilibrium holds—for now. Its maintenance requires sustained attention from both domestic actors and international partners committed to Malawi’s long-term stability and development.

References

-

Malawi Broadcasting Corporation. (2026, February 15). Mutharika’s SONA signals economic recovery path – Experts.

-

Malawi 24. (2026, February 17). Phiri blasts Chithyola as Minister who presided over plunder in SONA clash.

-

The Times Group. (2026, February 5). Malawi, Rwanda to deepen trade ties, harness AfCFTA.

-

United Nations. (2025, January). Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

-

PIJ Malawi. (2026, January 28). MALAWI BANKS AS CREDITORS’ SURETY TO SECURE IMF LOAN.

-

Malawi 24. (2026, February 13). “What we delivered in four months, some failed in five years” — Mutharika.

-

Malawi 24. (2026, February 13). I will shield no one- Mutharika warns corrupt officials.

-

LinkedIn. (2025, December 31). Fiber Optic Deployment to Enhance Regional Connectivity.

-

Oxford Public International Law. Regional Cooperation and Organization: African States.

-

Bid Detail. (2026, February 7). Malawi Project Notice – Malawi First Growth And Resilience DPO With A Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option.